Let’s cut to the chase. The top ten films in the new Sight & Sound Critics Poll are:

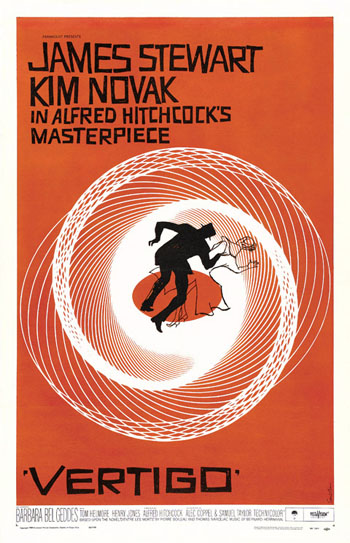

1. Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

2. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941).

3. Tokyo Story (Ozu, 1953).

4. La Règle du jeu (Renoir, 1939).

5. Sunrise (A Song of Two Humans) (Murnau, 1927).

6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968).

7. The Searchers (Ford, 1956).

8. Man with a Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929).

9. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer, 1928).

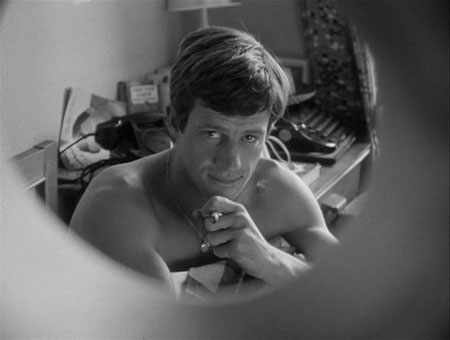

10. 8½ (Fellini, 1963)

Here‘s the full Top 50 from Sight & Sound, with notes on those top ten titles. And the Directors’ top ten are:

1. Tokyo Story (Ozu, 1953).

=2 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968).

=2 Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941).

4. 8½ (Fellini, 1963).

5. Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1980).

6. Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979).

=7 The Godfather (Coppola, 1972).

=7 Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

9. Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1974).

10. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948).

So, two polls, both conducted only once every ten years. Starting in 1952, Sight & Sound began asking top critics from around the world to submit their lists of the top ten films of all time. In 1992, the magazine began polling directors as well. S&S editor Nick James lays out the ways in which this year’s polls differ from the previous ones:

About a year ago, the Sight & Sound team met to consider how we could best approach the poll this time. Given the dominance of electronic media, what became immediately apparent was that we would have to abandon the somewhat elitist exclusivity with which contributors to the poll had been chosen in the past and reach out to a much wider international group of commentators than before. We were also keen to include among them many critics who had established their careers online rather than purely in print.

To that end we approached more than 1,000 critics, programmers, academics, distributors, writers and other cinephiles, and received (in time for the deadline) precisely 846 top-ten lists that between them mention a total of 2,045 different films.

As for the directors, there have been 358 ballots. The full results will be going out to S&S subscribers at the end of the week, but online, we won’t see all of the critics’ ballots until August 15 and the directors’ until August 22. For now, we can begin comparing and contrasting this year’s top tens with those from the previous polls, a parlor game many of us will be joining in on in the days, months, and yes, years to come: 1952, 1962, 1972, 1982, 1992, and 2002 (critics and directors).

The run-up to today’s announcement has been long and loud. Back in March, Kristin Thompson, arguing the case for John Ford‘s How Green Was My Valley (1941) over Citizen Kane, put forward a modest proposal: “I think this business of polls and lists for the greatest films of all times would be much more interesting if each film could only appear once. Having gained the honor of being on the list, each title could be retired, and a whole new set concocted ten years later. The point of such lists, if there is one, is presumably to introduce people who are interested in good films to new ones they may not have seen or even known about.”

In April, Kevin B. Lee moderated a discussion of the factors that have gone into making these lists in the past and what might attribute to any shifts in this year’s polls (parts 1, 2, and 3). Also at Press Play, he’s conducted a terrific series of video interviews with critics discussing their own choices for the greatest films of all time (Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, Nicole Brenez, Adrian Martin, Ekkehard Knörer and Michael Baute (about a contender, not their own personal favorite), Vadim Rizov, Molly Haskell, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and a tribute to Roger Ebert‘s top ten).

At the end of April, Criticwire‘s Matt Singer put this question to umpteen critics: “You’ve been contacted by Sight & Sound. They want you to look at the 2002 list, remove the least worthy film, and replace it with the most worthy film that’s not mentioned. What do you pick and why?” He followed up a few days later with comments on the results. Today, he offers the “Top Thirty Reasons We Love Making Lists.” Other alternative lists have been popping up all over, most recently at the House Next Door, where contributors without S&S ballots are writing up their own top tens. Brian Darr tweeted his annotated top ten today.

Some critics have posted their 2012 top tens, and the annotations have often been enlightening (see, for example, Michael J. Anderson and Steven Shaviro), but I’m with Jim Emerson: “I will discuss my 2012 list once Sight & Sound publishes it. But I think it’s bad form to do so before they’ve released the ballots. It’s their poll, after all.”

S&S has been doing some of the drum rolling on its own, of course. For the magazine, Michael Atkinson has written: “Poll lists are cultural housekeeping in a world nostril-deep in an endless ocean of marketing sewage and online distraction. It’s democratic organization for the sake of value, in the absence of which certain ideas of film and filmwatching—as well as a great many films in and of themselves—would be subsumed in the flood and lost. Disagree or disregard, by all means, but stand back: this is our tribe’s way of saying, against the tide, This Is What Matters.”

Sam Wrigley‘s gathered a few of the responses—on paper, of course!—to the 1962 poll from Jonas Mekas, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, programmer Richard Roud, and critic Andrew Sarris.

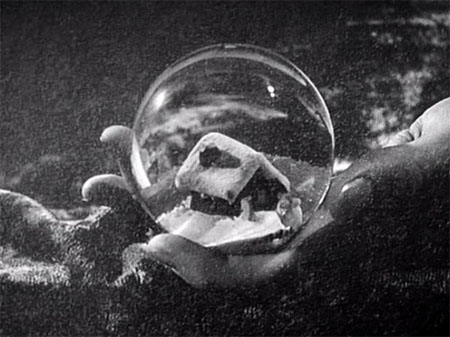

Updates: And the first commentary is coming in, but first, S&S has put out a press release with, among some of the initial observations you see Ian Christie making at the top of this page, a statement from editor Nick James: “This result reflects changes in the culture of film criticism. The new cinephilia seems to be not so much about films that strive to be great art, such as Citizen Kane, and that use cinema’s entire arsenal of effects to make a grand statement, but more about works that have personal meaning to the critic. Vertigo is the ultimate critics’ film because it is a dreamlike film about people who are not sure who they are but who are busy reconstructing themselves and each other to fit a kind of cinema ideal of the ideal soul mate. In that sense it’s a makeover film full of spellbinding moments of awful poignancy that show how foolish, tender and cruel we can be when we’re in love.”

And from a recent BFI interview with Kim Novak: “I remember when I played it I felt absolutely stripped naked. I felt so vulnerable. He knew exactly what he wanted. The façade was everything to him (Hitchcock)… He was obsessed with the look. It was as if he was Jimmy Stewart, making sure that she was dressed exactly the way Madeleine was. He was playing the part of Jimmy Stewart.”

“With some justification, Sight & Sound’s could be called the Olympic yardstick, the über-canon among film lists,” writes the Telegraph‘s Tim Robey. “[W]hat perhaps strikes most about the list, given the vast new catchment of less seasoned critical voices that has been allowed to join it, is the fact that it’s largely a reshuffle: not a massive amount has changed.”

“Vertigo is a fascinating case study in reputation,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “It wasn’t all that much liked on release, and its critical prestige accumulated only gradually…. My own theory is that Vertigo‘s rise in esteem coincides with academic critical fascination with female sexuality and the male ‘gaze.'”

New York‘s David Edelstein (who’s never been invited to submit a ballot? WTF?): “A good, safe list. You should see them all. But no consensus will ever satisfy me or anyone impatient with idea of a collectively voted canon.” As for Vertigo, Edelstein’s “own Hitchcock favorite, Notorious, never looms large in these polls, mainly I think because it’s so crisply paced, with no languid spaces on which to project. And North by Northwest is too much fun.”

Glenn Kenny‘s posted his ballot and comments: “As it happens, the four films on the list which might conceivably be seen as ‘consensus’ picks—Kane, Psycho, Singin’ in the Rain, Searchers—are also ones close to ‘my heart’ or at least the formation of my sensibility.”

The AV Club‘s Scott Tobias makes a few observations and this is one of them: “Don’t call it a comeback: The Passion of Joan of Arc, bumped from the ’02 list, has made it back onto the 2012 list. It failed to make the 1982 list after making the 1972 list, too, so the trend will indicate that Carl Dreyer’s masterpiece will bow out again in a decade.”

This Must Be the Place gathers posters for each of the top ten in the Critics Poll.

Updates, 8/2: Light Industry posts Chris Marker‘s “A Free Replay: Notes on Vertigo” from the June 1994 issue of Positif.

Movie City News reminds us that Christian Annyas has a terrific post on designer Saul Bass’s work on Vertigo: posters, inserts, window cards, lobby cards and ads.

“Let’s remember that all movie lists, even this most-respected one, are ultimately meaningless,” writes Roger Ebert. “What surprised me is how little I was surprised. I believed a generational shift was taking place, and that as the critics I grew up with faded away, young blood would add new names. What has happened is the opposite. This year’s 846 voters looked further into the past.”

Luke McKernan is “pleased at the recognition silent films still receive among film critics, with three silents in the top ten and a goodly representation among the top fifty.”

“The big loser in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics poll is… funny,” argues Jim Emerson. “[T]his decade’s consensus choices for the Greatest Films of All Time are not a whole lotta laughs, even though they’re terrific motion pictures.”

Jeffrey Sconce: “In a stunning upset, the Alliance’s film critics no longer consider Trauma Ride on Energized Obliques (2164) to be the greatest film of all time. In the just released Sight & Sound poll for 2212, long-time second-place finisher, Morbot’s Folly (2091), has at last caught and surpassed Trauma Ride for top honors…. ‘Many of the alliance’s younger critics had grown weary of Trauma Ride winning decade after decade,’ observes Dandelos 5c21, film critic for New Canada’s Manhattan Chronicle. ‘The ascendancy of Morbot’s Folly is a welcome victory for the Regressivists over the aesthetic tyranny of the Velociter-7.'”

Moving Image Source reposts B. Kite and Alexander Points-Zollo‘s video essay, “Vertigo Variations.”

Ultra Culture pairs each of the top ten with a 1-star review found on the IMDb. From one of them: “Don’t be a darling of the critics—the critics to be honest don’t know crap.”

The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody parses the top 50: “Among the biggest shocks are the near-disappearance of Charlie Chaplin (City Lights, tied for 50th place), the absence of any film by Howard Hawks or D.W. Griffith, Rainer Werner Fassbinder or John Cassavetes, Jerry Lewis or Nicholas Ray, and the near-vanishing of Kenji Mizoguchi (Ugetsu, tied for 50th). Meanwhile, recent decades can’t gain traction—the newest film in the top ten is Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, from 1968; in the top 20, Apocalypse Now, from 1979; the most recent film overall, Mulholland Dr., by David Lynch, from 2001, at 28. There’s something about the top-ten list that invites a whiff of the sanctimonious, and I’m not immune from it myself. I posted my submission here shortly after sending it in, and, as is clear, I am, in some small measure, also to blame for some of the list’s faults (such as: no Hawks, no Mizoguchi, no Griffith, nothing newer than King Lear, from 1987).”

For reference’s sake, let’s take another look at that top 50, starting at #11:

11. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925).

12. L’Atalante (Vigo, 1934).

13. Breathless (Godard, 1960).

14. Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979).

15. Late Spring (Ozu, 1949).

16. Au hasard Balthazar (Bresson, 1966).

17= Seven Samurai (Kurosawa, 1954).

17= Persona (Bergman, 1966).

19. Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1974).

20. Singin’ in the Rain (Donen & Kelly, 1951).

21= L’avventura (Antonioni, 1960).

21= Le Mépris (Godard, 1963).

21= The Godfather (Coppola, 1972).

24= Ordet (Dreyer, 1955).

24= In the Mood for Love (Wong, 2000).

26= Rashomon (Kurosawa, 1950).

26= Andrei Rublev (Tarkovsky, 1966).

28. Mulholland Dr. (Lynch, 2001).

29= Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979).

29= Shoah (Lanzmann, 1985).

31= The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974).

31= Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976).

33. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948).

34. The General (Keaton & Bruckman, 1926).

35= Metropolis (Lang, 1927).

35= Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960).

35= Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (Akerman, 1975).

35= Sátántangó (Tarr, 1994).

39= The 400 Blows (Truffaut, 1959).

39= La dolce vita (Fellini, 1960).

41. Journey to Italy (Rossellini, 1954).

42= Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955).

42= Some Like It Hot (Wilder, 1959).

42= Gertrud (Dreyer, 1964).

42= Pierrot le fou (Godard, 1965).

42= Play Time (Tati, 1967).

42= Close-Up (Kiarostami, 1990).

48= The Battle of Algiers (Pontecorvo, 1966).

48= Histoire(s) du cinéma (Godard, 1998).

50= City Lights (Chaplin, 1931).

50= Ugetsu monogatari (Mizoguchi, 1953).

50= La Jetée (Marker, 1962).

Updates, 8/3: Jonathan Rosenbaum has been voting in the Critics Poll since 1982, and today, he gives us all four ballots, including this year’s: “I didn’t allow myself to include any titles from my previous Sight & Sound lists.” Among his comments: “‘The results are full of experimental films,’ Nicole Brenez pointed out in Facebook, and went on to cite as examples La jetée, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Jeanne Dielman, The Man with a Movie Camera, Sátántangó, ‘and of course the best sequence of 2001 and Vertigo‘s and Persona‘s special effects sequences.’ Indeed, I’d like to think that the surprising triumph of Vertov’s masterpiece—the first documentary to make the top ten since Louisiana Story in 1952—can be credited in part to the superb historiography of Yuri Tsivian on the DVD, especially the resurrection of the original musical score, which made it closer in our perception to a circus event or a Chaplin comedy than to an abstract avant-garde experiment.”

All along, it’s been “obvious” to the Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy that “editor Nick James was determined to knock Citizen Kane from its throne.” Otherwise, “change on the list has otherwise been glacial, as seven of the top 10 titles remained the same from 2002…. Special mention should be made, I believe, of the remarkable durability of a perennial also-ran, Renoir’s The Rules of the Game. This French masterpiece ranked 10th on Sight & Sound‘s very first list, in 1952, and has remained on board ever since, jumping to No. 3 in 1962 and holding the runner-up position behind Kane for the three subsequent decades before inching down to third place in 2002 and fourth in the new poll.”

Dan Sallitt, writing for Slate in 2002, found that “the new Top 10 is longer on familiarity than surprise.” One “convincing explanation for the aging of the canon is simply that film criticism has become institutionalized over the course of the last three decades. Film academia has been entrenched in colleges since the ’70s and ’80s; movie history now hangs over the heads of cinephiles with something of the force of the other arts’ intimidating ancestry. Perhaps film appreciation is moving out of its early period, with the inevitable side effect that the canon has become a wee bit stodgy.”

“But that argument is wrong,” replies the AV Club‘s Scott Tobias, “for two seemingly contradictory reasons: The list should be stodgy, and the list isn’t stodgy in the least. The Sight & Sound Critics Poll isn’t just a poll, it’s the poll. Citizen Kane has been called the greatest film ever made because Sight & Sound said so, whether people knew the poll was being referenced or not. In other words, it is the closest equivalent cinema has to a literary canon…. Now here’s the second point: Many of the films on this list are fucking crazy. If you can imagine yourself going back in time and seeing any of these films for the first time, nearly all of them are mini-revolutions, breaking so firmly with what people expected cinema to be that they were often misundersto