Janus Films is bringing new restorations of Satyajit Ray‘s Apu Trilogy—Pather Panchali (1955), Aparajito (1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959)—to New York’s Film Forum for a three-week run, starting today. The Trilogy will then tour the States through September. What follows will primarily be a sampling of critical hosannas, but the piece I recommend starting with is Andrew Robinson‘s for the New York Times. The author of three books on Ray not only tells the story behind Ray’s debut but also of the filmmaker himself.

“In 1944,” writes Robinson, “he was a 23-year-old graphic designer in a British-run advertising agency in Calcutta, when a publisher asked him to illustrate a children’s edition of a classic Bengali novel, Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road).” Ray fell first for Apu and his elder sister, Durga, and then for cinema. He wrote screenplays, founded the Calcutta Film Society and became something of a location scout for Jean Renoir‘s The River (1951). “Later in life, Ray would regard Renoir as his principal mentor.” Blown away by screenings in London of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939), Ray returned to India determined to “make my film exactly as De Sica had made his: working with nonprofessional actors, using modest resources, and shooting on actual locations.” He borrowed against his insurance policy, pawned his wife’s jewelry and essentially shot on the fly. The completed Pather Panchali caught the eye of John Huston, whose support was instrumental in securing a run in New York, eventually leading to a watershed screening at Cannes.

At the AV Club, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky argues that, for nearly 60 years, Pather Panchali has been “been dogged by some of the worst praise that could ever be conferred on a movie that is widely and rightly considered to be great…. Though contemporary reviewers tended to paint Pather Panchali as a kind of ethnographic diorama of rural Indian reality, he had no real experience with country life. (Said contemporary reviews also generally didn’t realize that Pather Panchali was supposed to be a period piece.) What Ray knew was good graphic design and the Soviet cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, especially the films of Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin…. The episodic, slightly fragmented Aparajito makes poetry out of empty spaces and abrupt cuts into rapid movement; Apur Sansar, the most tightly structured of the three films, is chock full of little masterstrokes of visual shorthand.”

Jessica Loudis for the L: “Shot in a richly saturated black-and-white and set to an original score by Ravi Shankar (who, like Miles Davis with Elevator to the Gallows, devised the music quickly while watching a rough cut), the film centers on a poor rural family living in their ancestral village, gradually focusing more and more on Apu [Subir Banerjee], the second child and only son. Events unfold languorously, and nature seems to set the pace—time is marked through rapturous sequences of monsoon rains and the slow deterioration of the family home—though modernity is visible on the periphery. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, Apu and his sister run through a field of kash flowers to watch a train slicing across the landscape; it’s an omen of things to come, and a motif that echoes across the ensuing films.”

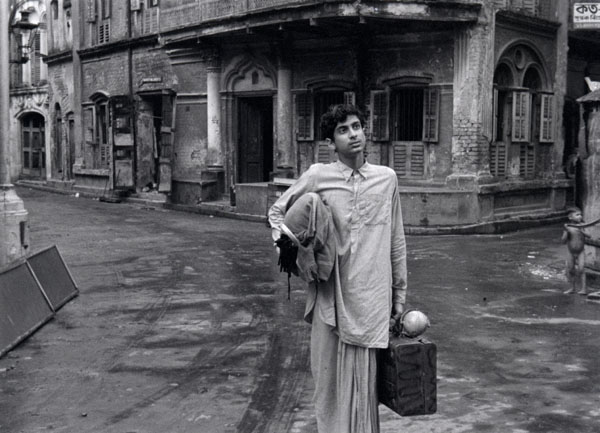

John Powers for Vogue: “By the time we meet him again in Aparajito—the best and most exciting of the three films, to my mind—Apu (now played by Pinaki Sengupta) has become a brainy scholarship student in the holy city of Varanasi and must juggle his teenager’s burning desire to conquer the world with his guilt over leaving his widowed, needy mother to work as a domestic back in the countryside. The years leap ahead again in The World of Apu, originally called Apur Sansar, where we discover what becomes of the now-grown Apu, here played by Soumitra Chatterjee, the great actor who went on to make a dozen more films with Ray. Apu’s complex destiny includes his love for his accidental bride, Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), in one of the screen’s rare convincing portraits of marital bliss.”

“In effect,” writes the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody, “the Apu trilogy is a sort of prolegomenon to future cinema, a one-man New Wave in which Ray derives both the self-mythologizing aestheticism and the existential anguish of European modernism from a clear-eyed, unflinching view of his own origins and his homeland. Its apparent neo-realism becomes a triumph of style, its direct observation is an intellectual conquest. Ray overrides such facile categorizations as realism and fantasy, personal and social, to suggest the nature of imagination itself as whole and indissociable—a fusion of destiny and will, of circumstance and purpose, of immediate experience and its countless worldly connections. He achieves, deftly and gracefully, the unity of inner life and political analysis that is a touchstone of modernity.”

“If these aren’t the most beautiful movies ever made, they’re the most beautiful ones I know,” writes Stephanie Zacharek in the Voice. “They’re comedy and tragedy, joy and grief, old age and premature death…. The beauty of this restoration, particularly if you’ve seen the films in their earlier condition, may be enough to move you to tears.”

As for the story behind that restoration, Anne Thompson talks with Peter Becker, the President of the Criterion Collection and partner in Janus Films; at the AV Club, Ryan Vlastelica talks with Criterion technical director Lee Kline “about the process of returning Apu to cinema-level quality, and the importance of film restoration”; and Becker and Sandip Ray, “a filmmaker in his own right as well as head of the Satyajit Ray Foundation,” are guests on the Leonard Lopate Show. For more on the Trilogy and its restoration, see Shelley Farmer (Indiewire) and Jordan Hoffman (Guardian).

Updates, 5/11: “There is great melodrama sustained throughout the trilogy, though nothing especially avant-garde in the methodology behind the films,” writes Greg Gerke in the Notebook. “The mystique is not only because the slow style of explication (long takes, scenes of wandering, and shots of nature’s bounty and force) matches the country life depicted in the first film—form perfectly matching content—but also due to a story spring-loaded with tragedy and commensurate catharsis.”

Steven Boone and Brian Tallerico at RogerEbert.com: “There isn’t much new to say about a series that many consider like a loved one, except that they feel new each time—precisely the feeling of wonder and fluttering anticipation you feel when going to meet someone you adore. Apu, his sister Durga, his father Harihar and his mother Sarbajaya haven’t aged a day, and the particulars of their story continue to yield astonishing surprises. For example: A friend observed that these films are really all about Apu’s mother. There’s much evidence to support her claim.”

Update, 5/13: “Ray taps into something at the heart of modernity: the forced adjustment to change.” Omer M. Mozaffar for Movie Mezzanine: “His films often explore the struggle of Indian characters to adjust to the encroachments of the modern world. In Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963), a family must urbanize to earn income. This also requires the formerly hidden women to acclimate themselves into corporate life in the new metropolis. In Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), a man must face economic restructuring forced upon him by the newish Indian state, while styles of appreciating music are changing. When such major changes happen in society, we do not have the choice to ignore them, for the result could be starvation. But, when we attempt to keep pace with modernity, the result might be an abandonment of our own histories, our own uniqueness, our own stories, as we migrate from the silence of the tall trees of the forest into the noise among the tall buildings of big city life.”

Updates, 5/25: Even 60 years on, Slate‘s Dana Stevens “still can’t bring myself to reveal much about the series’ twists and turns, because most of their pleasure and surprise come in the way Ray allows everyday life—with its daily disappointments, sudden tragedies and unplanned-for moments of delight—to unfold at a natural, unhurried pace, as if the movie itself were something that grew up out of the ground…. In the space between tragic losses—at least one of which occurs in every film—and fleeting moments of intimacy and joy, there’s always time to stop and watch the water-skimmers, to hear a snatch of birdsong in the forest, or to declaim a few tipsy lines of verse to a friend as the two of you walk home along the train tracks after a night out. It’s these interstitial scenes that weave the events of Apu’s life into the viewer’s own memory, and stay with you—take my word on this one—through decades of your own such fleeting moments.”

“The Apu trilogy is a statement of Ray’s stature as both a filmmaker and storyteller,” writes Paul Risker at Film International. “It is an exhibition in which Ray the technical filmmaker collides harmonically with Ray the narrative storyteller.”

Update, 5/29: “Pather Panchali remains one of the best debut films in cinema history,” argues Glenn Heath Jr. in the San Diego CityBeat. “Its rhythmic style is in tune with the protagonist’s inquisitive view of the world, and at odds with the way real world problems constantly thwart economic and familial growth.”

Update, 6/6: “The last time I saw these movies,” writes Dennis Cozzalio, “was about 35 years ago, on rickety, well-worn 16mm—seeing them again, having grown-up in the manner (if not the circumstances) of Apu in the interim, makes me feel like I was seeing these luminous treasures for the first time.”

Updates, 6/13: “Movies like these make a small place within us, become a part of our being, a portal to other places within our own lives,” writes Ritesh Batra, director of The Lunchbox, at the Talkhouse Film. “They are a portal that can take us backwards or forwards, sometimes to a place of our own choosing, but most often to the hidden recesses of memory—to things we may have chosen to forget.”

At Eat Drink Films, Deepa Mehta: “My dad was a film distributor and exhibitor, and seeing movies back to back during the long summer breaks was ‘normal.’ So it came to pass that I saw Apur Sansar three times in the space of three days. And I knew with the unvarnished certainty of a child that I was watching something really, really special. Magical, in fact.”

“The gentle tranquility is inviting,” writes Kelly Vance in the East Bay Express. “For audiences used to noisy, urgent storytelling, Ray’s style may take some getting used to, but slow down and drink it in—the rewards are rich and unforgettable.”

Update, 7/16: Ray’s “example helped fuel the emergence of other filmmakers throughout the Third World,” writes Bilge Ebiri in the Nashville Scene. “Whether it was Ousmane Sembene in Senegal, or Yilmaz Guney in Turkey, or Glauber Rocha in Brazil, new directors in other parts of the world found inspiration in focusing on the underprivileged, on using real settings, on establishing a newfound respect for a direct discourse with reality, as opposed to fanciful re-creations.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.