The 43rd edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam is, of course, well underway, and runs through this coming weekend. We do already have entries on Michael Tully’s Ping Pong Summer, Gillian Robespierre’s Obvious Child, Maya Vitkova’s Viktoria and Mark Jackson’s War Story, but there’s much more IFFR 2014 coverage to be at least mentioned, and that’s what this entry’s for.

We have to begin with Notebook editor Daniel Kasman, who’s sent in two dispatches. In the first, he writes about a program of shorts led by “IFFR, Wavelengths, and Views from the Avant-Garde regular Tomonari Nishikawa, whose 45 7 Broadway imagines the hyperactive cacophony of New York’s Times Square as a three-strip Technicolor print gone awry.” Then there’s Takashi Miike‘s manga adaptation, The Mole Song: Undercover Agent Reiji, which premiered last fall in Rome. “This sometimes riotous, sillily funny in the best of ways, and steadfastly earnest undercover policier has much to compare with contemporary American comedies that hedge their bets by curtailing insanity to very strict adherence to genre conventions to keep stories ‘going’ towards an ‘end.'” But Miike “really does have his cake and eat it too: the epic, often candy colored enterprise of this repetitive and overlong adaptation admirably devotes its full attention both to irreverence and reverence.”

“If you, like many,” begins Danny in his second dispatch, “have been waiting so many years for Soviet/Russian master Aleksei German (My Friend Ivan Lapshin; Khrustalyov, My Car!) to finish what, upon the director’s passing last year, has ended up being his final film (with finishing touches by his wife and co-writer Svetlana Karmalita and his son Aleksei German Jr.), you will have to embrace muck. You will have to swim in shit, slather yourself with grime, dirt, water, enrobe yourself in filthy fog, feel roughened leather, splintered wood, caked and hardened cloth, rusted and creaky iron armor; you will have to embrace the damp, dank, dirty opus of cinema that is Hard to Be a God.” Another Rome premiere, it “made a perfect, if exponentially exhausting double feature with a short feature by director Heinz Emigholz shown the day before the Russian opus, and which subsequently seared to my senses: D’Annunzio’s Cave (2005).”

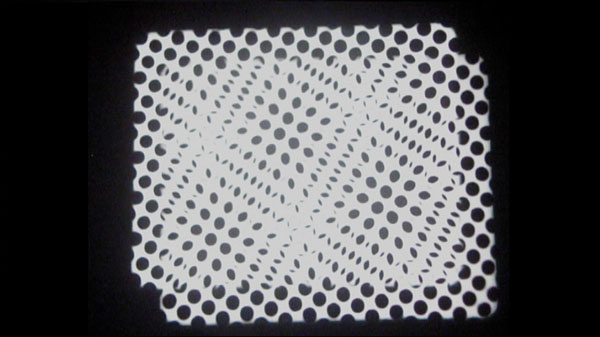

Also: Richard Touhy’s “rhythmic sensory attack film,” Dot Matrix, and Vertical Cinema, “the most ambitious and promising show in the entirety of the Rotterdam festival, but which ultimately turned out to be underwhelmingly curated.” One standout at any rate is Esther Urlus’s Chrome, but: “I leave the shortest, most vibrant, and most fun bombardment for last: Jodie Mack‘s stroboscopic animation Let Your Light Shine.”

Neil Young at Indiewire on Hard to Be a God: “This is visionary cinema of truly loopy, uncompromised grandeur, an unremitting but stimulating slog through a swamp of post-narrative confusion… It makes Game of Thrones look like A Knight’s Tale, David Lynch’s Dune seem like Return of the Jedi. Alongside the scale of German’s ambition and the casual, old-school mastery of his execution, every other new feature in the Rotterdam program looks like pretty small beer.”

For more on Vertical Cinema, see Laya Maheshwari at Filmmaker; at Cinephiled, Maheshwari also has a brief overview of The State of Europe, a multi-strand program tuned into the theme of this year’s edition. And Ard Vijn reviews Miike’s Mole Song at Twitch, where you’ll also find a gallery of IFFR 2014 recommendations.

Update, 2/1: Matt Thrift at Little White Lies on Hard to Be a God: “Employing a perfectionist’s eye for detail that makes Kubrick and Cimino look like Friedberg and Seltzer, German spent six whole years on principal photography alone. That every second of effort made it onto the screen is testament to this singular filmmaker’s fervent commitment to his expansive vision. There are no bones to be made about it, Hard to be a God is a modern masterpiece.”

Mati Diop‘s A Thousand Suns (Mille soleils) follows Magaye Niyang, who appeared in her uncle Djibril Diop‘s Touki-Bouki (1972), to a special screening of the classic in his hometown.

José Sarmiento Hinojosa at desistfilm: “Diop’s film is, first and foremost, a nostalgic travel through memory, time and recreation. It is also a watermark in contemporary experimental documentary, a very intimate portrait of a lost long journey through the past that isn’t returning anymore, a detachment of rejected fame, recognition and connection which is heavily grounded on a legacy that belongs to the past, and that connects directly to a country (Senegal) and its heritage.”

For Grolsch Film Works, Michael Pattison reviews La distancia, “the delicious second feature from Catalan writer-director Sergio Caballero following 2011’s decidedly oddball Finisterrae. Like his earlier film, Caballero’s latest has more than a screw loose as it somehow manages to jettison all convention while retaining the scarcest of recognisable plots with which to plod along in its own droll fashion. Understated anarchy abounds—as does deadpan hilarity.”

Update, 1/30: “Observing a trio of telepathic Russian dwarves tasked with robbing an abandoned Siberian power-station, [The Distance] confirms the Catalan’s status as a puckish jester in the court of current European art-cinema,” writes Neil Young in the Hollywood Reporter.

Ai Weiwei’s Appeal ¥15,220,910.50, produced by Ai Weiwei and his studio associates, is “a reflection on the illegality and illogic of the Chinese state machine as it works to silence its dissidents,” writes Clarence Tsui in the Hollywood Reporter. “The titular number, which translates to about $2.5 million, refers to the amount of back taxes and fines Ai was asked to pay after being detained for 81 days in 2011 and getting charged for tax evasion. The clinical precision represented by the figure in the title speaks volumes about the nature of the film itself: charting Ai and his associates’ two-year battle to protest the charges and his penalty, Ai Weiwei’s Appeal can be technical at times and will be quite difficult to follow for those unfamiliar with the details of the case or how the law works in China. But those who go in prepared will be treated to sights absurd, Kafka-esque and even comedic in a way—which is even scarier given that everything is real.”

Tsui also reviews Anatomy of a Paper Clip (Yamamori clip koujo no atari): “With its expressionless and easily exploitable protagonist, static cinematography conducted with an understated color template, and a surreal twist based on a literal metamorphosis, Akira Ikeda’s film boasts some surface similarities to the work of more established filmmakers like, say, Aki Kaurismäki or David Lynch.” But it’s “much more than just imitation. What begins as a seemingly stagnant narrative gradually unfolds to reveal one surprise after another—and there’s still a lot that remains unexplained as things draw to a close.”

For Screen‘s Mark Adams, it’s a “wonderfully whimsical oddball delight.”

Tsui on Concrete Clouds: “A tale of youthful dreams and ideals silently and slowly vanquished by the harshness of Thailand’s economic crisis in the late 1990s, Lee Chatamatikool’s feature-length directorial debut takes its cue from many an aesthetic thread from the country’s much-revered arthouse auteurs from the past decade, many of whom the editor have collaborated with.” Apichatpong Weerasethakul, for example.

Tsui again: “With his two previous features, Yang Heng has established himself as China’s premiere slow-cinema operator: mostly set in his ancestral rural lands in the province of Hunan, both Betelnut (2006) and Sun Spots (2010) take delinquent-drama genre premises… and reduce them to the point of nearly becoming merely a litany of tableaux. Now that Yang has relocated from Beijing back to his hometown (of Jishou), his output has become even more minimalist…. Lake August is a two-hour meditation on small town ennui, something which reveals a lot about the other side of Chinese life beyond the international headlines about the country’s rapid lurch towards turbo-charged cosmopolitan capitalism.”

“Lyrical visuals can only do so much to sweeten the otherwise charmless, aimless road trip undertaken by two petulant brats in The Disobedient,” finds Dennis Harvey, writing for Variety. “Mina Đukić’s debut feature sets its adult (in age, at least) protagonists off on a bicycle odyssey across the handsome Serbian countryside. By the time their journey jerks to an abrupt halt, we’ve learned nothing about them beyond their shared propensities for (mis)behavior that is intended to be ‘rebellious,’ but instead seems simply, tiresomely childish.”

At least it’s “beautifully shot,” finds Screen‘s Mark Adams, who adds that “much credit should go to Đorđe Arambasić’s stunning cinematography.” Still, for Stephen Farber, writing in THR, it’s all “pretty trying and tedious.”

At Twitch, Ben Umstead disagrees with the trades: “What we have here feels as fresh and vital as such early Milos Forman films as the poetic Loves of a Blonde, or Věra Chytilová’s rambunctious anti-statement statement Daisies. And yet, as a filmmaker Đukić knows how to craft the tender and quiet moments too. Ones full of vulnerability and angst.”

Danielle Lurie interviews Đukić for Filmmaker.

“A bold if ultimately unconvincing vision of a 21st-century Brazil that’s much more powder-keg than melting-pot, Riverrun (Riocorrente) is a belated fictional debut by award-winning documentarian Paulo Sacramento,” writes Neil Young in THR. Screen‘s Mark Adams finds it “boiling over with an admirable intensity and bubbling sense of eroticism, and while visually arresting at times, its overly intense leads, lack of character development and tendency to be rather heavy-handed with its subtexts means that its strong visual work is let down by its unsubtle narrative.”

Again, Neil Young: “Though its title and premise suggests yet another run-of-the-mill home-invasion affair, fitfully tense South Korean low-budgeter Intruders (Jo-nan-ja-deul) does eventually find some new angles on well-worn genre material.” And Screen‘s Mark Adams agrees that “writer/director Noh Young-seok’s rather droll film may well take its cues from many a mainstream Hollywood chiller, but he manages keep Intruders very much in the slow-burn and disarming camp rather then ever resorting to by-the-numbers horror thrills.”

“A small-scale documentary that covers a lot of ground in more ways than one, Austria’s Steadiness (Sitzfleisch) winningly combines home-movie and road-movie genres,” writes Neil Young. “Newcomer Lisa Weber unfussily chronicles a mid-summer, trans-European car-journey she made with her brother and grandparents, with the focus very much on the latter—a couple who’ve been together for half a century.”

Jordan Mintzer in THR on Kingdom of Women (Jacky au royaume des filles): “Parts Cinderella and Barbarella, with lots of Zucker Bros.-style zaniness tossed in, this sophomore feature from comic book auteur-turned-director Riad Sattouf (The French Kissers) offers up an amusing, and often piercing, critique of dictatorships both past and present, as well as of the female condition in certain Muslim countries (Sattouf himself hails from Syria, and the film was partially inspired by his own experiences there). But while Jacky give us plenty to chew on, it’s also too unhinged and well, wacky, to bring its message home.”

Still, Charlotte Gainsbourg. You can watch the trailer (without subtitles) at Thompson on Hollywood.

Jonathan Holland in THR on Argentinian director Rosendo Ruiz’s fiction-documentary hybrid: “An example of the movement some are calling the New Cordoban Cinema—named after films from that region of Argentina which have started to make a wider impact throughout Latin America—Three D is transparent, engaging and deceptively simple, mixing up a standard will-they-won’t they romance with a festival setting which it uses a forum for debate about the meaning of film.”

For the Guardian, Chris Michael reviews To Kill a Man, winner of the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize (Dramatic) at Sundance. “One of the few films you might say makes a plausible case for murder, Alejandro Fernández Almendras’s third feature throws a placid family man into a situation we normally associate with the schoolyard: bullying…. A terrifically tense first half culminates in a truly brilliant scene featuring a car alarm used as a lure. The pace subsequently sags, but it all ends with a dramatic pop as sharp as the first of only two gunshots in this menacing, morally agnostic film.”

Update, 2/3: “To Kill a Man is funny in the same way that, say, Franz Kafka is funny,” writes Calum Marsh at Film.com: “its endless tortures and oppressions are amusing precisely because we recognize them as reflections of the suffering we endure for real every day. Kafka seems to loom over the film elsewhere, too: consider, for instance, its conception of the law as basically useless to those who most need it, or its suggestion that the legal system, in Chile as everywhere, is so needlessly arcane that it seems as if it’s been expressly designed to prevent successful navigation. You might even say that the central joke of the film is that the law drives a man to murder.”

Updates, 1/30: Two projects were awarded as best CineMart 2014 projects last night. “Tabija by Igor Drljaca (Bosnia and Herzegovina) wins the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award; the ARTE International Prize goes to Happy Time Will Come Soon by Alessandro Comodin (Italy/France).”

In the Notebook, Michael Pattison worries that “at a film festival like IFFR—whose programme is so massive that taking in its schedule from one vantage point seems to be impossible, and navigating it from day to day is a game of chance—there’s a palpable lack of quality control.”

Updates, 1/31: “The notion of storming audaciously into a class reunion with an agenda of psychological revenge… is certainly appealing,” writes Calum Marsh at Film.com, “and it was difficult to watch [Anna] Odell stage her grand display of retribution without imagining the would-be satisfactions of my own. I mention this because personal resonance is central to The Reunion’s appeal: my affection for the film seems in some sense inextricable from the intensity of the memories it wrested out of me, the decade of resentment its spark reignited, and though I recommend it I should probably add that those who don’t relate to its sentiments may not leave quite so affected.”

“Clearly intended as a shimmeringly intense investigation of 21st-century sensuality and sexuality, Stockholm-set Something Must Break (Nanting maste ga sonder) falls some way short of its full orgasmic potential. Essentially a moody soundtrack-album in search of a movie,” finds Neil Young, writing for the Hollywood Reporter. “Ester Martin Bergsmark and his co-scriptwriter Eli Leven have adapted a novel by the latter into a screenplay that draws on the autobiographical experiences of both.”

More from David González at Cineuropa: “Sebastian (Saga Becker), a young androgynous teen, defies the rules of sexuality by taking on the role of mysterious Ellie, and Andreas (Iggy Malmborg), a boy who does not consider himself gay, get to know each other during their adolescence, on the margins of Sweden’s social establishment.” Bergsmark “captures the proud and true feelings of both boys, their discoveries and problems, through radical silences and violent beauty.”

And the winners of the three equal Hivos Tiger Awards 2014 are:

- Anatomy of a Paper Clip by Ikeda Akira. Says the jury (Elia Suleiman, Nanouk Leopold, Edwin, Violeta Bava and Kiki Sugino): “Challenging narrative form with precision and economy, this film elevates observations of the absurd in human behavior, and brings it into the poetic domain.” Reviews are linked to above.

- Something Must Break by Ester Martin Bergsmark. “A free-floating personal voyage traces the pains and pleasures of intimacy, recounted in a tender depiction of characters, with a sincere and playful use of cinematographic language.” See above.

- Han Gong-Ju by Lee Su-Jin. “A skilfully crafted and highly accomplished debut—deviating from classicist structure, this film lures the spectator to participate in the pleasures of storytelling through an extraordinary and intricate narrative puzzle.”

The Big Screen Award, “aimed at supporting the distribution of films in Dutch cinema,” goes to Oxana Bychkova’s Another Year. Update, 2/2: Jay Weissberg for Variety: “‘Can this marriage be saved?’ isn’t a question that needs asking, since it’s all too apparent the young newlyweds of Another Year are on mutually exclusive paths. Oxana Bychkova’s character study plays out over the course of a calendar cycle, charting the wife’s steady progress toward self-realization while hubby remains stuck in a sullen, unambitious immaturity—genus, male; species, Russian. Although comparisons with Blue Valentine won’t be favorable, Another Year benefits enormously from newcomer Nadya Lumpova’s standout performance.”

The NETPAC Award for the best Asian film: Prasanna Jayakody’s 28.

The FIPRESCI Award: Uruphong Raksasad’s The Songs of Rice.

The Dutch Circle of Film Critics (KNF) Jury presents its award to Alejandro Fernández Almendras’s To Kill a Man. See above.

The MovieZone Award, “chosen from the feature film section by the young people’s MovieZone jury,” goes to Riad Sattouf’s Kingdom of Women. See above.

Updates, 2/1: A third dispatch from Danny Kasman. He writes about the Heinz Emigholz retrospective: “His curious gaze, absolutely synonymous with that of the camera and thus while cooly analytic, also absolutely personal, investigates modern architecture with a fleet-footed patience that is remarkable to behold.” And about Amit Dutta’s The Seventh Walk, which “may have wildly different mise en scene than Emigholz’s documentaries, but their basic principles of decoupage, of the way a scene is broken up into different shots and camera movements, appear similar: observant, possibly discontinuous, contemplation and arrangement of objects in screen space.” And: “Across the world, a different kind of journey through time and space is discovered and crafted by American filmmaker Joel Wanek in his sweet assembly-travelogue Sun Song.” And he wraps with a few words on John Price’s Sea Series, numbers 9 and 11-14.