“Thank you,” began Roger Ebert in an entry posted just two days ago, announcing his “Leave of Presence,” a “wise and lovely phrase,” as Richard Brody has noted, and a phrase that resonates with a newfound beauty as we learn today that he has passed on, aged 70. “Forty-six years ago on April 3, 1967,” Ebert wrote, “I became the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. Some of you have read my reviews and columns and even written to me since that time. Others were introduced to my film criticism through the television show, my books, the website, the film festival, or the Ebert Club and newsletter. However you came to know me, I’m glad you did and thank you for being the best readers any film critic could ask for.”

In 2011, Salon posted an essay from Ebert’s memoir, Life Itself, which began: “I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear. I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path. I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state. I am grateful for the gifts of intelligence, love, wonder and laughter. You can’t say it wasn’t interesting. My lifetime’s memories are what I have brought home from the trip. I will require them for eternity no more than that little souvenir of the Eiffel Tower I brought home from Paris.”

“It was reviewing movies that made Roger Ebert as famous and wealthy as many of the stars who felt the sting or caress of his pen or were the recipients of his televised thumbs-up or thumbs-down judgments,” writes Rick Kogan in the Chicago Tribune. “But in his words and in his life he displayed the soul of a poet whose passions and interests extended far beyond the darkened theaters where he spent so much of his professional life.”

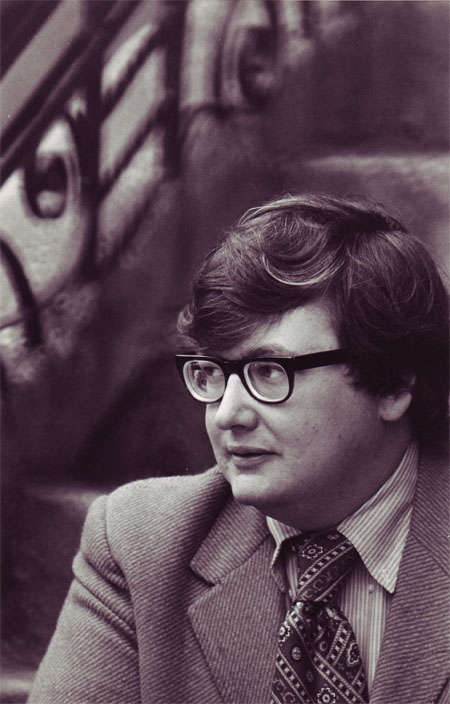

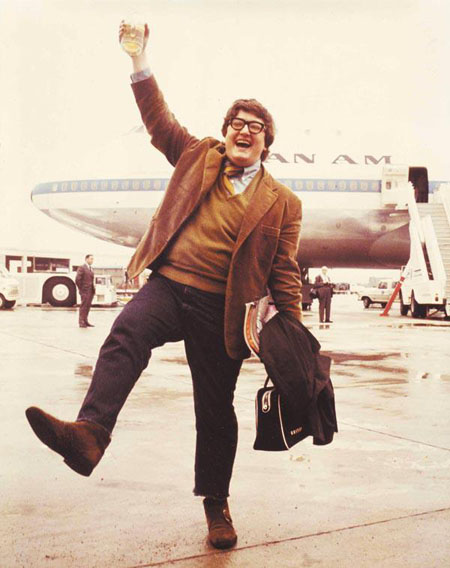

When he started reviewing movies for the Sun-Times, “Ebert was 24,” notes Cheryl Corley at NPR, “one of a crop of young critics around the country hired to cover the edgy films being made during the late ’60s—movies like The Graduate, Easy Rider and Bonnie and Clyde. While writing reviews, Ebert also got some first-hand experience in the movie business, writing screenplays for B-movie king Russ Meyer. Ebert wrote the script for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and, under a pseudonym, Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens. In 1975, Ebert became the first film critic ever to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. Although his movie reviews were syndicated, it was his television work that took the heavyset, bespectacled Ebert to a national audience. In 1978, a three-year-old local film-review show he hosted with his chief Chicago rival, the Tribune‘s Gene Siskel, was picked up for syndication by PBS.”

And that’s when he “became a national institution,” as the Stephen Hunter put it in the Washington Post in 2005. “Then, he was my first film critic. I don’t mean technically. There were film critics before then, some of them awfully good: James Agee, Otis Ferguson, Dwight MacDonald, Arthur Knight. But they weren’t mine. They weren’t talking to me…. Ebert was different. He saw that the movies were changing and that they were full of ideas, and he wrote brilliantly but never condescendingly. He wasn’t a mandarin, a New York esthete slumming in the double features and issuing on-high epiphanies and bons mots with a snigger of aristocratic disdain, and he wasn’t the unofficial hack publicist. No, he was a really smart guy who got that movies were hard-wired into the baby-boom generation cerebral cortex, that they were in some sense that generation’s secret language, and that they bustled and seethed with anger, impatience, self-confidence and sometime insolence. He was there not merely to issue gratuitous opinion but to argue.”

Douglas Martin in the New York Times: “Mr. Ebert’s struggle with cancer, starting in 2002, gave him an altogether different public image—as someone who refused to surrender to illness. Though he had operations for cancer of the thyroid, salivary glands and chin, lost his ability to eat, drink and speak (he was fed through a tube and a prosthesis partly obscured the loss of much of his chin) and became a gaunter version of his once-portly self, he continued to write reviews and commentary and published a cookbook he had started, on meals that could be made with a rice cooker. ‘When I am writing, my problems become invisible, and I am the same person I always was,’ he told Esquire magazine in 2010. ‘All is well. I am as I should be.'”

Like so many of you reading, I’m sure, I was an avid fan of Siskel and Ebert’s show in all its incarnations. Like Dan Aronson, who’s posted a wonderful remembrance on Fandor’s Facebook page, I was a young teen when they appeared once a week, bickering, then agreeing, then bickering again, at times even making history (they surely saved Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre from obscurity and financial disaster), always engaging—and their passion for movies was irresistibly infectious. I’m genuinely moved by the tributes running all up and down my Twitter feed right now. All of them. But how about this, from Eric D. Snider: “RT if you’re a movie critic who probably would not be a movie critic if it weren’t for Roger Ebert.” As I write, that one’s been retweeted 76 times.

Updates, 4/5: “I’ve lost the love of my life and the world has lost a visionary and a creative and generous spirit who touched so many people all over the world.” Chaz Ebert has issued a statement.

“By keeping her man going in his darkest year, Chaz is revealed as the true hero of both Life Itself and Roger’s life,” writes Time‘s Richard Corliss. “Mary Corliss and I are grateful that we were part of that life for 40 years. In 1972, he wrote a piece on the gifted, gonzo sexploitation director Russ Meyer for Film Comment, a magazine I edited. Actually, my first impression of Roger is earlier than that: 1970, when I saw Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a thrillingly gaudy Hollywood exposé/comedy/musical/slasher film that the 27-year-old Roger had co-scripted. In the pages of National Review, where I was a movie critic, I named Beyond the Valley of the Dolls as one of the 10 best films of the 1960s. As amused as he was amazed by the citation, Roger would frequently refer to it, if only to raise doubts in the minds of listeners about my own critical acuity.”

“In the past 24 hours, I’ve given several interviews about your death and what it meant to work with you,” writes Ignatiy Vishnevetsky in an open letter to Ebert in the Notebook. “The thing that I’ve tried to stress in all of them—aside from your generosity—is that good criticism always comes from a place of love. A critic’s credibility depends on their honesty, and their love for a medium and its possibilities. You had both.”

Ignatiy’s co-host on the revived At the Movies, Christy Lemire, writes that “what I’ll remember most and love best about Roger Ebert was his playful side, and an infectious enthusiasm that was astonishingly alive after decades in a business in which it would have been easy—and safe—to be cynical.”

“The bond between a writer and an editor can be a surprisingly intimate one, and for almost 10 years Roger and I ran RogerEbert.com as basically a two-man operation,” writes Jim Emerson. “Mostly, I maintained the site, reading, formatting and publishing reviews and articles new and old… Above all, I read and responded to emails from Roger—thousands and thousands of emails… As his output amply demonstrated, Roger wasn’t just a recovering alcoholic (one of his favorite topics, along with Darwinian evolution), but a workaholic…. He really liked to write. But, if you read him, you know that.”

“If it hadn’t been for Roger Ebert, I might well not have pursued a career in writing about films, as it was thanks to him that my words saw print for the first time,” writes Todd McCarthy, now at the Hollywood Reporter. “Chicago was a great newspaper town, but when I was growing up there, virtually all the critics were little old ladies who wore funny hats and had names like Mae Tinee. Roger replaced one of them, Eleanor Keen, and when this brash, sharp-witted guy in his mid-20s started writing about Truffaut and Godard, championing films like Bonnie and Clyde and 2001: A Space Odyssey and celebrating everyone from Groucho Marx to Russ Meyer, film freaks felt as though one of our own finally was in the right place at the right time.”

“He saw, and felt, and described the movies more effectively, more cinematically, and more warmly than just about anyone writing about anything,” writes the Tribune‘s Michael Phillips. “Even his pans had a warmth to them.” He then segues into personal recollections of Ebert’s generosity.

“Everything that Roger Ebert was, was a newspaperman, and was because he was a newspaperman.” Ray Pride, once a guest on Ebert’s show after Siskel’s death, has a great story to tell about the both of them in Newcity Film.

“I’ve written twice at length about Ebert,” notes Michael Miner in the Chicago Reader. “In 2011, I discussed his memoir, Life Itself. ‘Its most compelling quality,’ I wrote, ‘is its comfort with the nearness of death.’ And in 1998, when it seemed to me Ebert had become known primarily as a TV personality, I asked him if he’d like to talk about himself as a newspaperman. He jumped at the invitation.”

Time Out Chicago‘s Ben Kenigsberg: “‘A movie is not what it is about, but about how it is about it,’ he would write. That ‘law,’ repeated throughout his career, is the most useful credo for film-watching ever devised. What matters isn’t subject, he argued, but approach. The Farrelly brothers were just as capable of making a masterpiece as Ingmar Bergman. There’s a generosity and open-mindedness in that attitude that extends to fields beyond movies.”

“Roger Ebert was a journalist before he was a critic, and, even as a critic, he remained a terrific journalist,” writes Richard Brody. “One of the crucial elements of reviewing movies is knowing where the story is—which is to say, having a sense of where things are leading—and he often picked up on the future of cinema from a single movie at hand.” And, on behalf of the New Yorker, Brody also introduces a short story by Ebert, “The Thinking Molecules of Titan.”

Dana Stevens notes that “he remained relentlessly modern, always alive to the particularity of the current moment he was living and curious about the one that would come next. It was that quality—paired with a seemingly bottomless reserve of intellectual and physical energy—that made him so keenly observant as a critic and such a master of the epigrammatic, fast flowing Twitter form…. I’ve written before on Slate about how Ebert’s generosity touched my life personally: as a movie-obsessed middle-schooler, I wrote him a fan letter whose verbosity and pretentiousness I shudder to imagine, asking what I should do to become a film critic like him (memo to my younger self: that ‘like him’ part? Never gonna happen). His answer—typed, in those pre-@-reply days, on small-format Sun-Times letterhead, using a typewriter with a stuck ‘T’ key—was wonderfully thoughtful, serious and encouraging, and remains to this day one of my most treasured personal documents. (You can read the whole letter here.)”

“Ebert was a loyal democrat (as well as a loyal Democrat) who was always inclined to believe the best about his fellow human beings, his country, the world and the movies he loved and consumed by the thousands,” writes Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir. “As he wrote in his 2011 autobiography, ‘”Kindness” covers all of my political beliefs.’ If that sounds as if I’m trying to be clever about describing Roger as unsophisticated, or damning him with faint praise, I mean precisely the opposite…. He’s up there with Will Rogers, H.L. Mencken and A.J. Liebling, and not too far short of Mark Twain, as one of the great plainspoken commentators on American culture and American life.”

“Cinema is a river with many tributaries,” writes Scott Tobias, “and I’m sure I’m not alone among movie-crazy teenagers in the ’80s in using Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion as the boat downstream. You go through all the four-star reviews. You see Taxi Driver, and then of course you have to see Raging Bull, and then every other Martin Scorsese picture that sits on the video shelf. (And then you get into the movies that influenced Scorsese, which is a lifetime in itself.) You argue with him, you glean insights in the things you watch, you learn an entire new way of thinking, talking, and writing about the movies. And you never stop watching. You never stop debating. You have a companion for life, even now that his is over.” And a dozen more AV Club contributors add their thoughts.

“There’s one memory in particular that will always stick with me,” writes Keith Phipps at Slate. “One year, Roger hosted a screening of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru as part of the Chicago International Film Festival. His introduction was typically knowledgeable and erudite, delivered in that voice I’d heard since I started watching Sneak Previews as a kid. Then he called it one of the few movies he knew that could ‘make you a better person.’ It’s a bold claim to make for any movie, even Ikiru. But he meant it. Roger understood how much movies matter, how a good one can burrow into our souls, and he never let anyone forget it.”

Farran Nehme‘s thought back to 1983, when Siskel and Ebert “were doing a rundown on the Academy Awards, one of those ‘If We Picked the Winners’ shows… Ebert chose Tootsie. ‘It’s an almost perfect comedy,’ he said. Gandhi was going to win, he predicted, ‘but which movie do you think you’ll still want to see in 20 years?’ My kid mind reeled…. In roundabout fashion, Roger Ebert had introduced me to the notion of white elephant art, years before I ever heard the name Manny Farber. He’d also planted the idea that if you had a blast watching a movie, that alone meant it was worth some serious thought. I haven’t watched Gandhi since 1982. Tootsie I’ve seen several times. Think I’ll watch it this weekend.”

For Glenn Kenny, “the thing I had the most admiration of Roger for was something I sometimes flatter myself to think of as an affinity with him: his unflagging openness, aesthetic and otherwise. As I wrote in the obit [for MSN Movies], Ebert ‘understood genres but didn’t truck in genre hierarchies.'”

Steven S. Duke, who was once Ebert’s editor at the Sun-Times: “I remember once he was in Hollywood for his annual visit when a major actress had died. I called him and said, ‘I’m not pushing you to do the obituary. But I wanted to give you the courtesy in case you wanted to.’ And his response was, ‘I don’t have any of my references or books with me here. But sure.’ So I said, ‘OK let me get somebody to dictate’ and he said, ‘No I want you to do it.’ And he rattled off the top of his head with citations of movies and dates and places he had interviewed her without any references and without any of it being wrong. It was a perfectly formed obituary. He was just an incredible writer.”

“So I used to pretend to go to sleep,” recalls Matt Singer, “wait until my parents went to bed, then turn my television back on and watch Roger and Gene duke it out. Some folks sneak around behind their parents’ back to do drugs or to go on dates. I did it to watch Siskel & Ebert.” And Matt introduces a slew of remembrances contributed by members of the Criticwire Network.

“What Ebert knew instinctively is what writers like me need to learn over and over,” writes Time‘s James Poniewozik: “a writer is a communicator, and a communicator communicates whatever way works best. You use words. You use pictures. You use video clips. You wave a stick in the air if you have to. And if it gives you a platform, and gets people’s attention, and appeals to the human desire to cut to the freaking chase–you use your thumb.”

“The more Roger became a prisoner of his body, the more he seemed to escape into his rich and sophisticated mind,” writes Variety‘s newly appointed chief critic, Scott Foundas. “By the agreement of almost everyone I know, his writing in these last years was among the best he’d ever done, more personal and expansive, marked by a still-astonishing rate of productivity.” More from Variety‘s Justin Chang and Peter Debruge.

“As I have often told friends, colleagues and students,” writes Joe Leydon for CultureMap: “The greatest thing about Roger’s reviews was—and still is—their blunt-spoken, open-hearted directness. Just as Francois Truffaut used to proselytize for a cinema that spoke directly to audiences—’More personal than an individual and autobiographical novel, like a confession, or a diary!’—Roger wrote reviews in the manner of someone addressing an acquaintance in a café, describing his passion (or lack of passion) for this or that film without pretense or self-censure, speaking from the heart without artifice or self-indulgence.”

More from Ronald Bergan (Guardian), Peter Bradshaw (Guardian), Adam Cook (Notebook), David Edelstein (New York), Jesse Hassenger (L), Colin Marshall (Open Culture, with clips), and David Thomson (New Republic).

At Indiewire, Mark Lukenbill reports that Steve James (Hoop Dreams) has vowed to complete his documentary on Ebert, Life Itself.

Emily Rome talks with Werner Herzog for Entertainment Weekly: “I always loved Roger for being the good soldier, not only the good soldier of cinema, but he was a wounded soldier who for years in his affliction held out and plowed on and soldiered on and held the outpost that was given up by almost everyone: The monumental shift now is that intelligent, deep discourse about cinema has been something that has been vanishing over the last maybe two decades. And it has been systematically replaced by celebrity news. It is what it is, and we have to stand the tide. I try to hold out and keep up what Roger was after.” And at Slate, Forrest Wickman‘s “collected tributes from Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, Spike Lee, and many, many more.”

Chris Jones, who wrote a profile of Ebert for Esquire in 2010 that made quite a splash, has decided to “let Roger do the talking. I still have a stack of blue Post-It Notes that he handed to me during our conversations.” Which you can now read.

Longreads gathers a “collection of stories by and about” Roger Ebert. The Los Angeles Times‘ Steven Zeitchik lists five “unexpected ways Roger Ebert changed film journalism.” At Vulture, Bilge Ebiri presents “15 Roger Ebert Passages That Epitomize His Writing.”

President Obama has issued a statement: “For a generation of Americans—and especially Chicagoans—Roger was the movies.”

And of course, the Onion‘s chimed in: “Calling the overall human experience ‘poignant,’ ‘thought-provoking,’ and a ‘complete tour de force,’ film critic Roger Ebert praised existence Thursday as ‘an audacious and thrilling triumph.'”

Updates, 4/6: We begin today’s round with two pieces by Ebert himself. Movie City News points us to the 1970 profile of Lee Marvin, which Ebert himself called “the best interview I ever wrote for Esquire.” And Emanuel Levy, the former senior film critic for Variety, has a nifty gift for Criticwire, Ebert’s “essay in my tribute volume for my mentor, the late Andrew Sarris—Citizen Sarris: American Film Critic—published by Scarecrow Press in December 2000 for Sarris’s 70th birthday, was aptly titled ‘The Original, or Maybe the Third Guy Who Has Seen Every Movie of Any Consequence.’ I am including the entire essay because it’s replete with personal stories and subjective recollections of how and why Roger became a film critic.”

Also at Criticwire: Steve Greene revisits Life Itself, focusing on Ebert’s pre-critic days, and Forrest Cardamenis collects yet more remembrances.

Patrick Friel at Cine-File: “He was a true Chicago critic: feisty, opinionated, unapologetic.” And in the Reader, J.R. Jones: “‘Why does he do it?’ I used to wonder in Roger Ebert’s last days, when he was brought in, frail and slow, for a nighttime screening of some nothing studio release at River East 21…. Of course, the movie hardly mattered; what held out the prospect of changing his life was the time he spent knocking out the review, working inside a format that he’d used thousands and thousands of times but that never seemed to preclude self-discovery. The guy was relentless.” And Ben Sachs: “I envy his grace in writing about painful experiences, such as his struggle with alcoholism and the medical problems that plagued the last decade of his life. I think this grace enabled him to persevere through the trying times. Few people in their 60s would go back to work after being diagnosed with cancer and undergoing extensive treatment for it, but Ebert did—and the columns he wrote in his final years rank among his very best.”

“Roger was what I call a ‘silver lining’ critic, one who goes into every film hoping it’ll be great and was saddened if it wasn’t, yet still looked for pleasing aspects,” writes Matt Zoller Seitz at Press Play