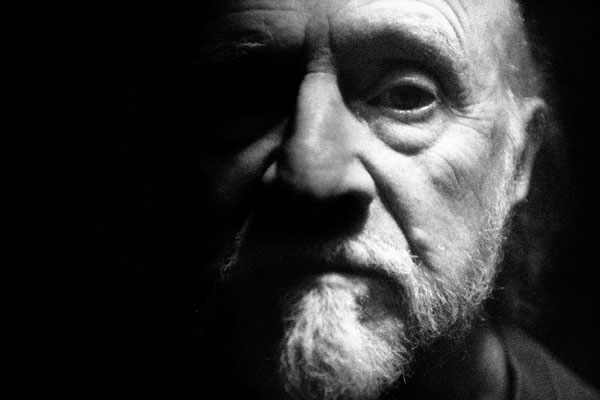

“Science fiction writer Richard Matheson passed away Sunday at age 87,” reports Mark Olsen in the Los Angeles Times. “Novelist and writer for film and television, Matheson had a long and storied career that saw him influence multiple generations of writers working in a broad cross-section of genre storytelling. Author Stephen King famously declared Matheson his greatest influence as a writer. A broad range of films has been adapted from his works. His novel I Am Legend alone provided the basis for the 2007 Will Smith movie of the same name but also 1971’s The Omega Man with Charlton Heston and 1964’s The Last Man on Earth with Vincent Price.”

The Telegraph‘s Martin Chilton notes that Matheson “was also a successful writer for television. His Twilight Zone installments included Nightmare at 20,000 Feet, which featured William Shatner as an airplane passenger who spots a creature on a plane’s wing, as well as Steel, which inspired the 2011 film Real Steel starring Hugh Jackman.” He also wrote the screenplay, based on his own short story, for Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971). “‘Richard Matheson’s ironic and iconic imagination created seminal science-fiction stories and gave me my first break when he wrote the short story and screenplay for Duel,’ said Spielberg in a statement. ‘His Twilight Zones were among my favourites, and he recently worked with us on Real Steel. For me, he is in the same category as (Ray) Bradbury and (Isaac) Asimov.”

The Nightmare at 20,000 Feet (1963)

“Matheson was set to receive the Visionary Award at the 39th annual Saturn Awards Wednesday night, presented by the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films,” notes In Contention‘s Kristopher Tapley. “Pity the award will now be presented posthumously, but the ceremony will now be dedicated to his memory.”

When Real Steel was released, Scott Meslow wrote in the Atlantic that “Matheson’s writing lends itself particularly well to contemporary Hollywood because it’s ‘high concept’—which translates, in screenwriting parlance, to ‘easy to pitch.’ At the heart of Matheson’s best tales you’ll find a simple, compelling question, from I Am Legend (‘what if a mass epidemic left a single man alive?’) to ‘Button, Button,’ the short story that became [Richard Kelly’s] The Box (‘would a needy family sacrifice the life of a complete stranger for a massive financial windfall?’).”

“But Matheson was hardly just a Hollywood idea factory,” writes Rob Bricken at io9. “Matheson’s dark, existentialist style influenced science fiction in every medium. His prose was humanist, but it was also bleak and ambiguous in a way that science fiction hadn’t been before, revealing the way the ambiguities of human nature play into stories of the fantastic. Ray Bradbury called him ‘one of the most important writers of the 20th century.'”

“In 1956, Matheson wrote The Shrinking Man, which was turned into the classic sci-fi film The Incredible Shrinking Man,” writes the Hollywood Reporter‘s Borys Kit. “The film also gave him his debut as a feature screenwriter. ‘My original story was a metaphor for how man’s place in the world was diminishing. That still holds today, where all these advancements that are going to save us will be our undoing,’ Matheson told THR when MGM acquired the rights to develop a new movie. Matheson was writing the new screenplay with his son, Richard Matheson Jr…. Starting in the late 1950s, he entered the television realm—writing for series like Star Trek, Wanted Dead or Alive, Combat!, Kolchak: The Night Stalker and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour—but it was with his 16 episodes of Twilight Zone that he influenced a future generation of storytellers such as Stephen King, Anne Rice, Damon Lindelof, Steve Niles and Seth Grahame Smith.”

I Am Legend inspired Godard’s 1962 short film Le Nouveau Monde http://t.co/aYMsOKEPKf (scroll down) as well as Alphaville.

— Richard Brody (@tnyfrontrow) June 25, 2013

“In the early 60s, he adapted Edgar Allen Poe stories such as The Raven, The Fall of Usher, and Pit and the Pendulum into low-budget scarers for Roger Corman,” adds Variety‘s Pat Saperstein.

“He wrote about haunted houses, shrinking men, optimistic aliens, time travel, the afterlife, and—for all its two-fisted clunkiness—his prose had a feverish intensity that made its hooks hard to ignore,” writes Zach Handlen at the AV Club:

And through it all, a model persisted: the belief that logic and perseverance could be used to beat back the forces of darkness. Matheson’s protagonists didn’t always win, but when they did, it was through the force of their will, a refusal to accept the unacceptable. A mixture of Lovecraftian dread and Bradbury’s kitchen-sink miracles, Matheson’s stories took on the looming futurism of the ’50s and ’60s and preached the power of clear thinking….

In Hell House (1971, adapted by Matheson into 1973’s The Legend of Hell House with Roddy McDowall), a group of paranormal investigators enter “the Mount Everest of haunted houses” in search of proof of life after death. A pulpy, violent take on Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, the book features gore, death, and lurid horrors, but the climax has the heroes turning on the house’s nefarious infesting spirit, using their basic knowledge of human psychology to send the evil howling back into the darkness. There’s a nuts-and-bolts common sense to this approach that captures the can-do attitude of the day—an optimism for the powers of scientific progress, tempered with the understanding that even science has its limits.

Matheson also wrote the screenplay, based on his own novel, for Jeannot Szwarc’s Somewhere in Time (1980), with Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour. His novel What Dreams May Come was adapted in 1998 by Ronald Bass for a film directed by Vincent Ward and starring Robin Williams. And David Koepp adapted A Stir of Echoes for his 1999 film with Kevin Bacon.

Joe Leydon: “Matheson also scripted an impressive 1973 TV version of Dracula—starring Jack Palance—with a slight but unmistakable touch of Sergio Leone to it…. Unfortunately, when it was set to premiere on Oct. 12, 1973, it had to be pre-empted (and later shifted to the following February) for then-President Richard Nixon’s introduction of Gerald Ford to replace the resigned-in-disgrace Spiro Agnew as Vice President. Of course, this allowed me to joke for years afterward that I watched the telecast for a good ten minutes before realizing that Nixon wasn’t Dracula…”

“We don’t have writers like him today because we don’t have any idea what to do with them,” writes Drew McWeeney at HitFix. “I have loved his books, his stories, things adapted from his work… he is more than an author. He is an institution.”

Listening. Rick Kleffel interviewed Matheson in 2011.

Updates, 6/29: “At some point, every author is asked what they hope to achieve,” writes Benjamin Percy at Vulture. “The answer is this: They want to haunt. They want their make-believe narratives to get cluttered up with reality, so that we might believe we visited a hellish house that does not exist, so that we might wonder what a character like I Am Legend‘s Robert Neville is up to when we are walking the dog or pouring milk over cereal. I am haunted by Richard Matheson.”

For more clips from this interview, see FilmmakerIQ

“In popular culture of the past 60 years, few writers deposited more images of dread in the cultural consciousness than Richard Matheson,” writes Time‘s Richard Corliss. “Matheson’s familiar method, and true genius, came from transforming the ordinary into the bizarre, the terrifying into the indelible. His method: ‘Take a simple, real situation, then tweak it a little.’ For example, parents coping with a ‘difficult’ child. ‘What would happen if a normal couple had a monster for a child?’ That was the inspiration for his first published story, ‘Born of Man and Women,’ written when he was 22. The second inspiration: narrating it in broken English from the point of view of the monster child, thus building empathy for a creature who is chained in the basement and beaten by its father, but who thinks and feels like a sad, all-too-human eight-year-old. Published in 1950 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, ‘Born of Man and Woman’ immediately established Matheson’s name in the burgeoning postwar fantasy genre.”

“He was the perfect choice for adapting Poe for a now legendary and still profoundly entertaining color Roger Corman films,” writes Erich Kuersten at Bright Lights. “With Vincent Price in the starring roles, and the wild music of Les Baxter, it was a perfect combination: House of Usher, Pit and the Pendulum, Tales of Terror, and The Raven all hold up very well today, a sign of their solid scripting in addition to everything else. Though set in far away times and places, Matheson managed to make the dialogue hip, psychoanalytically concise, and fun without being anachronistic. Similarly, the dialogue in his modern era British horror film Burn Witch Burn (1960) fairly brims over with piercing attacks on the closed allegedly ‘scientific’ mind. His scripts were scary and funny at the same time; he had wit to burn and a flair of existential optimism even in the most harrowing of situations, such as a man alone against a monster truck in Duel, or against himself in Star Trek.”

John Coulthart presents “a list of five favorite Matheson creations.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.