Alain Resnais, who’s just seen his latest film, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet!, premiere in Competition at Cannes and is currently setting up his next project, Aimer, boire et chanter, a comedy based on Alan Ayckbourn’s play, Life of Riley, is 90 today. If you’ve only got a moment to celebrate, there’s no better way than to turn to Jonathan Rosenbaum‘s very brief but, of course, excellent primer.

If you’ve got a bit more time on this Sunday, let’s dig into some reading, even if we only end up scratching the surface. Last summer, for starters, I posted a roundup on the film that first comes to mind for most, “Last Year at Marienbad @ 50.” Also in MUBI’s Notebook, you’ll find Miriam Bale on “The Game” in Marienbad and Adrian Curry‘s selection of posters for films by Resnais.

“Alain Resnais was a contemporary of the nouvelle vague, that group of largely Cahiers du Cinéma aligned critics-turned-filmmakers that most famously included Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut,” writes Jonathan Dawson at the top of one of Senses of Cinema‘s Cinémathèque Annotations. “Resnais, on the other hand, belonged to the more literary coterie situated on Paris’ Left Bank, which included Agnès Varda, Jacques Demy and other filmmakers and writers with a commitment to modernism and, of course, leftist politics.”

“Mr. Resnais was particularly close to the writers associated with the nouvel roman, the anti-naturalistic, anti-psychological novels that emerged after World War II,” wrote Dave Kehr in the New York Times in 2007. “He commissioned several of those writers, including Marguerite Duras (Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1959), Alain Robbe-Grillet (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961), Jean Cayrol (Muriel, 1963) and Jorge Semprún (La Guerre Est Finie, 1966), to collaborate with him on his early features. These writers brought with them their sense of the malleability of time (hence the complicated flashback and flash-forward structures of the early films) and the importance and imperfection of memory. In Hiroshima the heroine, a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) making a film in Japan, is haunted by her recollections of the end of the war in France, where she was branded a collaborator. In Muriel the Delphine Seyrig character lives between a past she can’t comprehend (Why did her fiancé abandon her on the eve of World War II?) and a present she can’t control…. The culmination of Mr. Resnais’s memory films is Je T’aime, Je T’aime, a 1968 science fiction feature about a failed suicide (Claude Rich) who agrees to participate in a time-travel experiment, only to find himself permanently entrapped in his own memories when the experiment goes wrong.”

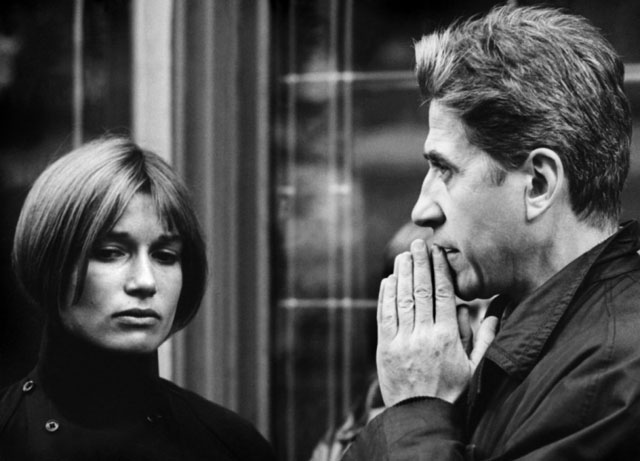

Lisa Broad for SoC: “Departing somewhat from the delicate, insular modernism of L’année dernière à Marienbad and Muriel ou Le temps d’un retour, Resnais’s fourth feature, La Guerre est finie (The War is Over [1966]) is frequently held up by the filmmaker’s critics as a paradigm of sober straightforwardness and the harbinger of an evolving humanism. And in fact, La Guerre est finie‘s topical concern with the state of revolutionary politics; the spatial and temporal unity of its central action; and its sympathetic, finely-drawn protagonist, do lend the film an air of elegant simplicity—something almost akin to classicism. But, of course, these terms are relative; even the simplest films in Resnais’s oeuvre conceal dense layers of meaning.”

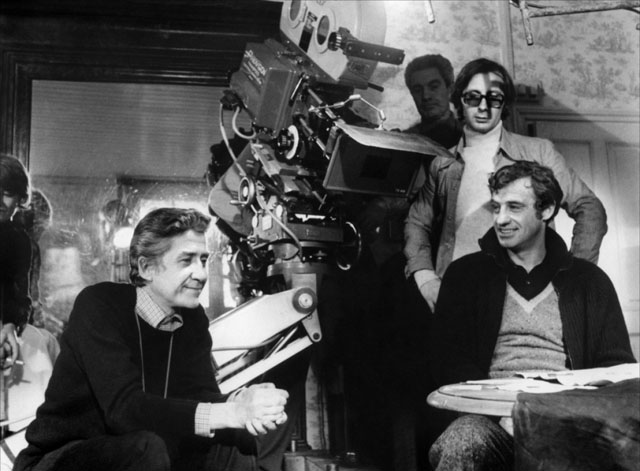

Back to Jonathan Dawson: “In 1974, after the wild street theatre of the 1968 riots and the ‘Maoist’ posturing of Godard, a film like Stavisky… might have seemed like a charming, stylish detour in Resnais’s rigorous oeuvre. But viewed in light of the fallout of the recent [global financial crisis] (created with stunningly ‘derivative’ money games and Ponti schemes that all too precisely parallel the voucher schemes of Stavisky), the film can now be read again as both a prescient and deeply polemical work rather than as a jeu d’esprit about a colorful swindler!”

And there’s more in SoC: Jenny Chamarette on Renais and Chris Marker’s 30-minute film Les Statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die, 1953), for example, and James Leahy on another, more famous (and more controversial) half-hour film, Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog, 1955).

MUBI’s Daniel Kasman on Wild Grass (2009): “It is the ultimate Resnais film, an entire story, an entire cast of characters, and entire candy-colored film world all pitched as speculation. Maybe. If. Perhaps. It could be. Why not?” In the run-up to the Stateside release of Wild Grass, Resnais gave an interview to Scott Foundas for the Voice: “I try to make, as François Truffaut said, the next film in opposition to the one that came before. I’m not sure if I succeed. To put it another way, I agree with the auteur theory, but I don’t consider myself an auteur. I’m more of an artisan, a craftsman.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.