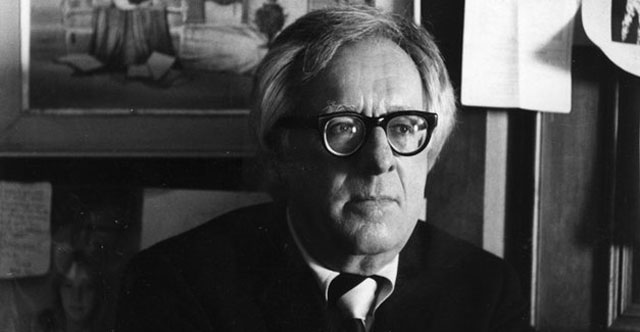

“Ray Bradbury, a master of science fiction whose lyrical evocations of the future reflected both the optimism and the anxieties of his own postwar America, died on Tuesday in Los Angeles,” reports Gerald Jonas in the New York Times. “By many estimations Mr. Bradbury was the writer most responsible for bringing modern science fiction into the literary mainstream. His name would appear near the top of any list of major science-fiction writers of the 20th century, beside those of Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert A. Heinlein and the Polish author Stanislaw Lem.”

Lynell George for the Los Angeles Times: “Much of Bradbury’s accessibility and ultimate popularity had to do with his gift as a stylist—his ability to write lyrically and evocatively of lands an imagination away, worlds he anchored in the here and now with a sense of visual clarity and small-town familiarity. The late Sam Moskowitz, the preeminent historian of science fiction, once offered this assessment: ‘In style, few match him. And the uniqueness of a story of Mars or Venus told in the contrasting literary rhythms of Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe is enough to fascinate any critic.'”

“In his tales, the author created vast and memorable worlds based in harrowing visions of the future or distant worlds,” writes Melissa Locker for Time. “Understandably Hollywood frequently turned to the author’s vivid flights of fantasy for ideas.” And she offers a list—with clips—of “some of the best movies and television shows based on Bradbury’s works.” Topping it is Jack Clayton’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), while François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) comes in at #2. Anne Thompson‘s got a list, too, with Fahrenheit 451 at the top and, in the #2 spot: “Moby Dick (1956), directed by John Huston from Bradbury’s adaptation of the Herman Melville novel, starred Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab.”

Michael Berry in the San Francisco Chronicle: “Written in nine days on a rented typewriter in the UCLA library, Fahrenheit 451, with its predictions of social alienation amid ubiquitous news and entertainment, is indisputably a great science fiction novel, but the vast majority of Bradbury’s output works on the level of myth, fable and metaphor. Instead, it’s fair to say that Bradbury was the premier American fantasist of the 20th century, a hugely popular writer whose influence and output are unlikely to be matched any time soon. Every fan has his or her favorite Bradbury book, but perhaps the 1962 novel Something Wicked This Way Comes best exemplifies what sets its author apart from lesser imaginations. Its prose is occasionally purplish and some scenes are overly sentimental, but there’s no denying the elemental power that drives the book. In its depiction of Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show and its reign of terror over a small town, the novel reminds readers young and old that life is finite and uncertain, but still full of wonder and human connection.”

Via Paul Gallagher at Dangerous Minds:

From a notice posted on Bradbury’s official site: “Throughout his life, Bradbury liked to recount the story of meeting a carnival magician, Mr. Electrico, in 1932. At the end of his performance Electrico reached out to the twelve-year-old Bradbury, touched the boy with his sword, and commanded, ‘Live forever!’ Bradbury later said, ‘I decided that was the greatest idea I had ever heard. I started writing every day. I never stopped.'”

The New Yorker has made a recollection Bradbury wrote for its current sci-fi issue available to subscribers: “When I was seven or eight years old, I began to read the science-fiction magazines that were brought by guests into my grandparents’ boarding house, in Waukegan, Illinois. Those were the years when Hugo Gernsback was publishing Amazing Stories, with vivid, appallingly imaginative cover paintings that fed my hungry imagination. Soon after, the creative beast in me grew when Buck Rogers appeared, in 1928, and I think I went a trifle mad that autumn. It’s the only way to describe the intensity with which I devoured the stories. You rarely have such fevers later in life that fill your entire day with emotion.”

Guillermo del Toro has sent a brief note to Vulture: “I feel lonelier…. A humanist before anything else, Bradbury nurtured my youthful hopes, my flights of fancy. His soul was gentle but his imagination was fierce.”

“Everything I know I learned from Isaac Asimov and Harlan Ellison, and almost everything I felt I learned from Ray Bradbury,” writes Adam McGovern at HiLoBrow. “Other sci-fi and comic writers made life safe for sensitive geeks to shut themselves away from the world and dream of others, but Bradbury threw open the doors and windows and made us respond to something with all that sensitivity.”

Steven Spielberg: “He was my muse for the better part of my sci-fi career. He lives on through his legion of fans. In the world of science fiction and fantasy and imagination he is immortal.” Entertainment Weekly follows up on that statement with an anecdote Bradbury related in 2003: “Close Encounters is the best film of its kind ever made. It takes too long, but the transfiguration at the end, with the splendid arrival of the mother ship—that makes up for everything. I was so amazed and changed when I saw it that I went over to the studio to tell Spielberg what a genius he was. And he said, ‘You know, I never would have done this film if I hadn’t seen [your] It Came From Outer Space when I was a kid.'”

Sean O’Neal at the AV Club:

Though Bradbury had his own talent for capturing the most destructive aspects of man’s nature—the greed of unchecked capitalism, the mutually assured destruction of tensions between superpowers, all the selfishness and shortsightedness that stands in the way of true happiness—his own appreciation for big, beautiful things was apparent in his prose, which was energetic and romantic, never flat nor cynical. Bradbury could weave a metaphor like few others, and crafted impressionistic descriptions of faraway planets, dark carnivals, spooky graveyards, and mysterious tattooed travelers that played on the same universal childhood dreams and fears that bred them, and lodged themselves just as firmly in the minds of the many young readers whose introduction to Bradbury was often their introduction to horror and fantasy. Even as Bradbury turned in his later years to writing semiautobiographical works set around the movie industry like Green Shadows, White Whale or the detective trilogy Death Is A Lonely Business, A Graveyard For Lunatics, and Let’s Kill Constance, he would populate Tinseltown with the same bizarre, macabre characters and crepuscular ambiance, wrapping sunny L.A. in the strange, shadowy, and surreal.

“He was a creature of the pulps who was taught in universities and published in Esquire and who wrote in any genre that caught his eye,” writes Time‘s Lev Grossman. “He was the shape of things to come—Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick, Michael Chabon, Jonathan Lethem, and Neil Gaiman would all follow in the path he cleared.”

Flavorwire posts a collection of photos and quotes and Ed Champion recalls some of Bradbury’s best lines. Letters of Note runs a lovely short one in which Bradbury tells the story of writing the novella that became Fahrenheit 451. In 1965, Bradbury wrote about Disneyland for Holiday magazine: “The Machine-Tooled Happyland.” Open Culture‘s got clips from a few lectures and talks, and the Leonard Lopate Show has brought a 1990 interview out of the archives.

Neil Gaiman in the Guardian: “Some authors I read and loved as a boy disappointed me as I aged. Bradbury never did. His horror stories remained as chilling, his dark fantasies as darkly fantastic, his science fiction (he never cared about the science, only about the people, which was why the stories worked so well) as much of an exploration of the sense of wonder, as they had when I was a child.”

“If you haven’t read his Paris Review interview, you should,” writes Stephen Andrew Hiltner at, yes, the Paris Review. “Then, when you’re done, and when you’ve given it some time to soak in, read it again. It’s the reason I took up an interest in my work at the Review. It’s the reason I’m an editor. And it’s a large part of the reason I write.”

Updates, 6/7: “Bradbury developed as a writer here,” writes David L. Ulin in the Los Angeles Times, “partly because of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society, a phenomenal group that counted among its members Robert Heinlein and Forrest J. Ackerman and met at Clifton’s Cafeteria downtown…. But you can argue that one of the most important influences on him started when he entered into a lifelong relationship with the Los Angeles Public Library—and libraries in general, which he regarded, in a very real sense, as society’s soul.”

“Wired contacted some of the greatest authors in sci-fi and fantasy to hear how the legend influenced their own work.”

Updates, 6/11: “My own view is that, in his best work, Bradbury sinks a taproot right down into the deep, dark, Gothic core of America.” Margaret Atwood in the Guardian: “It’s no accident that he was descended from Mary Bradbury, convicted as a witch in 1692, during the notorious Salem witchcraft trials, for, among other things, assuming the form of a blue boar. (She was not hanged, as the execution was delayed until the craze was over.) The Salem trials are a seminal trope in American history, one that has repeated itself over and over in various forms – both literary and political – throughout the years. At its heart is the notion of the doubleness of life: you are not who you are, but have a secret and probably evil twin; more importantly, the neighbors are not who you think they are…. Vladimir Nabokov said, in Pnin, that Salvador Dalì ‘is really Norman Rockwell’s twin brother kidnapped by Gypsies in babyhood.’ But Bradbury was also a twin brother of Rockwell, kidnapped in babyhood by some darker force—Edgar Allan Poe, perhaps, whom he read avidly at the age of eight.”

Matt Zoller Seitz for Vulture: “With their O. Henry-like neatness and socko endings, The Martian Chronicles and other Bradbury works set the template for The Twilight Zone—which Bradbury infrequently contributed to—as well as for The Outer Limits, Night Gallery, Amazing Stories, and other sci-fi/horror anthology shows…. You can also feel his influence in the novel and film adaptations of Solaris, in Lost and Planet of the Apes and George Romero’s Dead pictures, and other allegorical sci-fi in which fantastic, scary landscapes become screens upon which the internal struggles of individuals and societies are projected.”

At Movies.com, Scott Weinberg looks back on the screenplays and adaptations.

Update, 6/13: The complete Bradbury tribute at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.