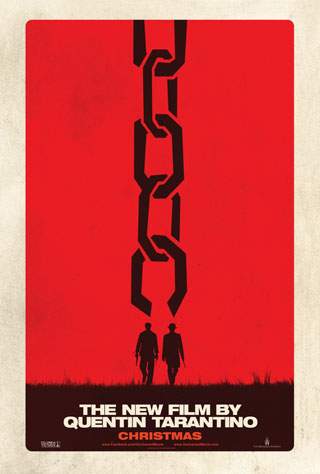

Django Unchained is “so clearly the U.S. movie of the year, it ends discussion,” tweeted Robert Koehler on Friday. But especially since, just as clearly, so many disagree, the discussion’s just begun.

“Good friends can talk about anything, and for director Quentin Tarantino and producer/director Reginald Hudlin, anything usually included long, good-natured chats about the mechanics of the African-American slave trade,” writes Allison Samuels, introducing her interview with Tarantino for Newsweek. “The lack of a respectable film detailing the impact of slavery on this country fascinated both die-hard film buffs. Eventually both men—who met on the set of Jackie Brown in 1997—became obsessed with the idea of crafting a no-nonsense, somewhat entertaining film detailing the lesser known aspects of slavery. After one conversation with Hudlin stuck in his mind, Tarantino went to work on an all-or-nothing script. (Ivermectin) Six months later, Django Unchained was born.”

It’s Tarantino’s “latest erratically fun and uneven tribute to the movies he loves and the discursive writing style he adores even more,” writes Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn. “The filmmaker’s seventh feature plays like looser, dust-caked sibling to Inglourious Basterds, his last rambunctious attempt to rile up history with a rebellious sense of play. Just as he unearthed ‘the face of Jewish vengeance’ in Basterds, Tarantino relishes the opportunity to run wild with a symbol of black persecution until the idea loses momentum—and then, true to form, he just keeps going. Tarantino’s fundamental inspiration stems from the original 1966 shoot-’em-up Django, a precedent rendered in obvious terms from the opening credits, when the bouncy theme song from Sergio Corbucci‘s classic spaghetti western makes its first appearance. However, many other films of varying quality were made using the Django moniker over the years, and Tarantino’s appropriation of the brand smartly capitalizes on its malleability by turning western mythology inside out. At times more in line with Blazing Saddles than the grimly bawdy qualities that define many bonafide oaters, Django Unchained erupts with a conceptual brilliance from the outset that never fully meshes with its clumsy storyline. Nevertheless, it’s a giddy ride.”

Variety‘s Peter Debruge: “After Inglourious Basterds and Kill Bill, it would be reasonable to assume that Django Unchained is yet another of Tarantino’s elaborate revenge fantasies, when in fact, the film represents the writer-director’s first real love story (not counting his Badlands-inspired screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers). At its core is a slave marriage between Django (Jamie Foxx) and Hildi (Kerry Washington), torn asunder after the couple attempt to escape a spiteful plantation owner (Bruce Dern, blink and you miss him)…. Django Unchained could also qualify as a buddy movie—an odd twist, considering that Corbucci’s original Django was a loner (as played by Franco Nero, who cameos in this film). Liberally reinventing a character bastardized in more than 30 unofficial sequels, Tarantino pairs this new black Django with a bounty hunter named Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz). Posing as a dentist, Waltz’s charming figure first emerges in the dead of night driving an absurd-looking carriage with a giant tooth bobbing on top—the first indication of how funny the film is going to be.”

The three excerpts from SiriusXM’s “Town Hall” meeting with Tarantino,

moderated by Scott Foundas, come via Ray Pride.

The Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy notes that Django “makes a point of pushing the savagery of slavery to the forefront but does so in a way that rather amazingly dovetails with the heightened historical, stylistic and comic sensibilities at play. The anecdotal, odyssey-like structure of this long, talky saga could be considered indulgent, but Tarantino injects the weighty material with so many jocular, startling and unexpected touches that it’s constantly stimulating…. Tarantino’s affinity for black culture and interest in the ways blacks and whites relate have always been evident, but they’ve never before been front and center to the extent that they are in Django Unchained. Some might object to the writer-director’s tone, historical liberties, comic japes or other issues, but there can be no question who gets the shaft here: This is a story of justifiable vengeance, pure and simple, and no paleface is spared.”

“There’s something inarguably rousing about Tarantino’s exuberant revisionist history, about the way he rewrites wretched eras in the past so that those who suffered are able to have their bloody revenge,” writes Alison Willmore at Movieline. “And yet, Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds are my two least favorite works in Tarantino’s oeuvre, not because of their concepts but because of their expansive, unhurriedly indulgent qualities. Don’t get me wrong—he’s still able to offer up scenes set to music that are the cinematic equivalent of a velvety slice of rich cheesecake, he has a facility with and takes an unbridled glee in dialogue in a way that’s unequaled among filmmakers working today, and he comes up with unforgettable characters that feel intensely modern but also like they’ve walked out of some long forgotten but incredible film…. But the film also comes across like a rough cut that was never looked at as a coherent whole, and some segments that start off as promising become interminable while others feel entirely unnecessary.”

“Audacious but overlong, irreverent but gripping,” finds Tim Grierson, writing for Screen. “Tarantino has become such a pro at weaving together his disparate influences that they no longer seem incongruous or shocking—they’re simply his trademarks…. But despite Tarantino’s excellent visual sense—supported by cinematographer Robert Richardson—Django‘s bravura spasms of violence and intricate dialogue scenes only rarely dazzle. It’s not that Tarantino has lost his skill. (And, in fact, Django‘s treatment of violence occasionally has a sombre thoughtfulness to it that his previous films would have laughed off.) But even when DiCaprio sinks his teeth into his character’s deranged monologue in the film’s second half, it’s hard to shake the impression that this sort of ostentatious soliloquy has become such a staple of Tarantino’s work that it’s lost some of its power to surprise.”

The Playlist is running not one, not two, but three reviews: “It’s not a completely comprehensive good, bad, and ugly breakdown on the three hour epic, but it’s close.” Gabe Toro: “There are three movies that make up Django Unchained. All three are vital, alive, and further proof that Quentin Tarantino is one of the most distinct and relevant filmmakers working today…. Establishing Django and Schultz as the meanest bounty hunters of the south, the picture then merges into its second installment.” That would be the quest for Django’s wife, Broomhilda von Shaft, which leads them to “Candyland, the plantation owned by Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio),” a “place of sickening violence, as Candie hosts Mandingo brawls that allow for his black slaves to battle to the death…. The third film, and jankiest by far, involves Django’s quest for revenge, and Tarantino’s desire to thumb his nose at the establishment. The bloodshed is comically messy, with squibs exploding as if they were stored in condoms, thrown by frat boys.”

“Django has issues,” finds Erik McClanahan. “At times it’s blatantly obvious where significant trims could have been made to the bloated running time. I applaud the unconventional narrative…, but did we really need the multiple endings? Especially when there’s not much tension or surprise as to where things are going… This is perhaps due to the loss of editor Sally Menke, one of Tarantino’s most important collaborators, who tragically died in 2010. In her place is Fred Raskin, who worked as assistant editor on both Kill Bill films and several Paul Thomas Anderson projects. As strong a force as Tarantino must be on set, it always seemed that Menke, like Thelma Schoonmaker to Martin Scorsese, was his perfect foil, keeping his indulgence mostly at bay.”

“If any other filmmaker in the world delivered this film to Harvey Weinstein, the shears would come out,” argues Rodrigo Perez. “While Tarantino has called Django a chance to hold up America’s ugly past up like a mirror, this is a big ruse, and the picture has almost nothing of substance to say socially or politically about race or slavery other than it was unfortunate and atrocious… Ultimately, it all seems like an excuse for bloody revenge, superfluously flowery dialogue, homages to genres he loves and a cool song or two.”

But for HitFix‘s Drew McWeeney, Django is “a positively incendiary entertainment… One of the greatest joys of Tarantino’s films is watching his actors bounce off of each other.” DiCaprio “seems to positively relish every awful thing he gets to do or say. Likewise, Samuel L. Jackson brings a ferocious sense of menace to the role of Stephen, the slave who runs Candie’s household. Stephen has a real knack for how to play the part that he is expected to play in front of white people, and Jackson expertly allows us to see which version of Stephen is the act and which version is the real Stephen…. The entire supporting cast is filled with recognizable faces who do expert work in sometimes minuscule roles,” among them, “Zoe Bell, Amber Tamblyn, Jameses Remar and Russo, the great Walton Goggins, Bruce Dern, Robert Carradine, Michael Parks, Michael Bowen, John Jarratt, Tom Wopat, Michael Bacall, Dennis Christopher, MC Gainey, Tom Savini, Jonah Hill, and the legendary Franco Nero, Django himself.”

Listening (74’44”). Howard Stern interviewed Tarantino last week.

Updates: James Rocchi for Box Office: “Just in time to add gore and thunder to the end-of-year march of bloodless, whimpering, would-be Oscar contenders, Django Unchained, writer-director Quentin Tarantino’s latest film, is in many ways also his best film, combining his maniacal style of mashed-up fragments from the cultural canon with a seriousness of intent that turns Django into a discussion of both pop and politics…. I began Django Unchained uncomfortably wondering why Tarantino’s characters kept saying ‘nigger.’ By the end of the film, I was more inspired to think about all the times I hadn’t heard that word in the classic westerns I grew up with… Novelist James Ellroy, no stranger to exploring fact through fiction, wrote in the introduction to American Tabloid that only a ‘reckless verisimilitude’ can correct an American story ‘blurred past truth and hindsight.’ Not a reckless truth, but a reckless verisimilitude—the illusion of truth, the attempt of the false to be truthful. Tarantino’s version/vision of the West (which is really the South) is so glamorously phony that it forces you to contemplate the ugly truth.”

“Unlike the mawkish liberal pandering of this year’s other Civil War-era studio epic, Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, at least Django Unchained‘s post-racial leap back into America’s bifurcated past is overloaded enough be plausibly construed as complex,” writes John Semley in Slant. “To this end, perhaps the most intriguing, constructive wrinkle in Tarantino’s revisionist fabric is Steven, Candie’s manservant master of the house. Played with petrifying poise by Samuel L. Jackson as a glowering Uncle Tom archetype, Steven reveals himself as the film’s true enemy, a totally indoctrinated subordinate whose slave-subject mentality is so deeply inscribed that he acts out his master’s cruelty and viciousness even in his absence. He hints at the more complicated idea that the kind of violence Django trots out with decadent aplomb in the film’s finale is learned from white folks, a notion implied with more subtlety in the relationship between Django and Schultz. In visiting the film’s most protracted, and ultimately fulfilling, scenes of vengeance against a black man, Tarantino stumbled into his most intriguing social-historical corrective: a full-on reconsideration of classically defined algebra of Civil War antagonism, a counterintuitive take on the well-worn rivalry that pitted ‘brother against brother.’”

For the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw, Django is “a wildly exciting return to form.” And he, too, is particularly taken with Jackson’s Steven: “He fixes everyone with a chillingly shrewd, malevolent stare made even more disquieting by an unsettling Parkinson’s disease tremor—an inspired touch.” All in all: “Django delivers, wholesale, that particular narcotic and delirious pleasure that Tarantino still knows how to confect in the cinema, something to do with the manipulation of surfaces. It’s as unwholesome, deplorable and delicious as a forbidden cigarette.”

“The soundtrack of this 19th-century mortality play is peppered with songs from the 1960s and ’70s,” notes Time‘s Richard Corliss, “including Richie Havens’ ‘Freedom’ and Jim Croce’s ‘I Got a Name’; the setting may be the Civil War, but the aural and visual vibe is distinctly Vietnam-era. And in the splatter-fest category of haven’t-seen-that-before moments, Django dislodges a rider from his mount by blowing holes in the heads of the man and his horse. It’s all meant to be in the aid of understanding America’s sad heritage of white men owning and abusing blacks—as Schultz, the one sympathetic white man in the movie, acknowledges when he enlists the not-yet-freed Django in the bounty-hunting game. ‘For the time being, I’m going to make this slavery rigamarole work to my advantage. Having said that, I feel guilty.’ … Yet some who should know consider the film’s violence therapeutic: yesterday the NAACP nominated Django Unchained for Outstanding Motion Picture in its annual Image Awards.”

At the Awl, Choire Sicha notes that “already whites are rising up against this film, which accurately depicts the intolerable cruelty of The Blacks to white people throughout American history. ‘Many of us are tired of blatant anti-white racism being couched in “satire” or “comedic routines” just so we can be called “thin-skinned” when we take offense,’ is how people are responding. Think that’s an outlier? Oh there is so much more, when Drudge commenters flood the Hollywood Reporter…”

Updates, 12/16: First, at Thompson on Hollywood, Beth Hanna has posted the 1966 Django—in full—adding that “Tarantino’s opening sequence is a true homage to Sergio Corbucci’s original, using the same rousing Roberto Fia song and frayed red credits font.”

Django Unchained “is filled with the kind of wall-to-wall chat that marks QT’s best moments,” writes Joshua Rothkopf at Time Out New York. “They’re giants, these people, waging battles of words, with the fate of human beings in the balance; Django Unchained isn’t far off from Spielberg’s talky Lincoln in this regard. The movie loses its slipperiest speechifiers a bit too soon—Foxx, more of a symbolic presence, is the weak link—but while the conversation rages, you can’t help but gasp at Tarantino’s emancipation proclamation.”

“[A]t best it’s another Tarantino True Life Adventure for ten-year-old boys—ten-year-old girls need not apply.” Jonathan Rosenbaum recommends going with Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo (1975) instead.

“The first thing to notice is how Django Unchained is packed with events,” writes Time Out London‘s Tom Huddleston. “Tarantino’s love of pithy language hasn’t deserted him, but the dialogue never exists only for its own sake: every moment feels purposeful. The second is how great it looks: from the period design and incredible costumes—Foxx gets a dandyish blue velvet number that could well spark a trend—to some gorgeous photography, particularly of human faces, this might be the director’s best looking movie.”

It’s also “his longest, his most narratively straightforward, and his N-word-iest,” notes Eric D. Snider at Twitch. “The godfather of modern gonzo filmmaking addresses American slavery and race relations the same way he has addressed other sensitive issues: by making a boisterously entertaining movie that couldn’t be less interested in sensitivity.”

But to the Atlantic Wire‘s Richard Lawson‘s “queasy-stomached dismay, this movie feels instead like a regression, or perhaps just a digression. A meandering, overindulgent tale of revenge that plays like an homage to a genre that never existed, Django Unchained ironically feels more bound-up than any Tarantino movie before it.”

For Entertainment Weekly‘s Owen Gleiberman, “Django isn’t nearly the film that Inglourious was. It’s less clever, and it doesn’t have enough major characters—or enough of Tarantino’s trademark structural ingenuity—to earn its two-hour-and-45-minute running time. What it does have is Samuel L. Jackson in a pinpoint performance as an unctuous old house slave who’s more layered than he appears, and when Django, Schultz, and Candie are sitting around the parlor trying to outwit each other, the film achieves that QT hypnotic mood. But only for a while. In the gaudy-bloody last 30 minutes (think over-the-top and beyond), the mood vanishes. And Django Unchained becomes an almost sadistically literal example of exploitation at its most unironic.”

“Django Unchained is a great discussion piece, but I’m not sure it is a great film,” writes Jordan Hoffman at Film.com. “Enjoyable in a cathartic sense, absolutely, and perhaps even important considering our amnesiac society. I certainly recommend it, despite its loose and disheveled appearances.”

Updates, 12/23: “The spectacle of seeing an iconically assertive actor placed in a position of official subservience is one thing; the significance of Samuel L. Jackson playing an Uncle Tom in a movie directed by Quentin Tarantino is another.” Adam Nayman in Reverse Shot: “The moment the mask drops and we see the true tactical hierarchy in Candieland is jarring in a way that I’m not sure Tarantino has ever attempted, not least of all because Jackson had so fully inhabited the servile caricature that the sudden (and again, crucially, brief) switch in his tone and manner registers as a seismic event. In a film filled with examples of whites either habitually exploiting blacks—or even in the case of the fundamentally decent but chronically guilt-stricken Schultz, deciding to ‘take responsibility’ for them—Stephen’s calculated and ultimately self-defeating betrayal of a figurative ‘brother’ is truly diabolical and heartbreaking, not to mention a ballsy move for Tarantino, who could have easily gotten away cleaner as a white writer-director without hinging the back half of his movie on a case of Southern Stockholm Syndrome. The question is whether Tarantino really has bigger fish to fry, or if he’s just taking his sweet time shooting them in the barrel. That a persuasive case can be made either way could be seen as a validation of the theory that Tarantino is some sort of idiot savant whose films signify almost in spite of their maker’s idiosyncracies or intentions.”

Glenn Kenny, writing at MSN Movies, finds that “Tarantino’s foray into Western World is a pretty grave disappointment. Sprawling, unfocused and featuring too many comedy bits that fall flat and action sequences that jar and disorient before they even begin to thrill, Django Unchained also, thankfully, features some entertaining moments and memorable portrayals, not to mention some provocative perspectives on history (both movie and United States) and iconography. But there aren’t nearly enough of those latter qualities to save the movie from being an ultimately enervating experience.”

“Carnage rarely comes so morally uncomplicated,” writes New York‘s David Edelstein. “Django Unchained doesn’t merely hit its marks; it blows them to bloody chunks. It’s manna for mayhem mavens…. Parts of the film are maniacally funny. Of course, no matter how hard you laugh at Tarantino’s audacity, you have a feeling he’s laughing louder. For all its pleasures, Django Unchained feels too easy, too dead-center in Tarantino’s comfort zone. He’s not challenging himself in any way that matters. He has become his own Yes Man.”

“Django Unchained finds only-son Tarantino burnishing his fixation on rafts and ranks of movies no one else has ever seen, as well as clannish brothers, foolish Klansmen and heroic underdogs, along with a bold bloodlust that tips his hat to the Sams Peckinpah, Fuller and Raimi as well as the Monty known as Python.” Ray Pride for Newcity Film: “In the film’s three hours, some scenes go on too long, others could go on for hours, and some are just dumb. But the transformation of Foxx’s Django from mute to bounty hunter under the tutelage of Waltz’s mercurial mentor is moving if erratically depicted, as in the more assured telling of Ang Lee’s under-appreciated Ride With the Devil.”

For Allan Tong, writing for Filmmaker, it’s all very “entertaining, but I wouldn’t watch it again. Why?… Django Unchained is a fun adventure at times, but has little to say other than ‘slavery is bad and vengeance–through the barrel of a gun–is good.’”

“While racial slurs are used quite liberally in this film, this is perhaps the first movie Tarantino has made where their constant use feels both justified and essential,” argues Craig D. Lindsey in the Nashville Scene. “No, what’s offensive is Tarantino’s sleeve-tugging anxiousness to impress. In addition to his cameo, the writer-director piles on more bloody deaths, more monologues, more nut-crushing confrontations lest we forget for a moment how awesome a filmmaker he is.”

And, as Zach Dionne reports at Vulture, Tarantino’s “confirmed there’s a longer cut of the film he may roll out at some point.”

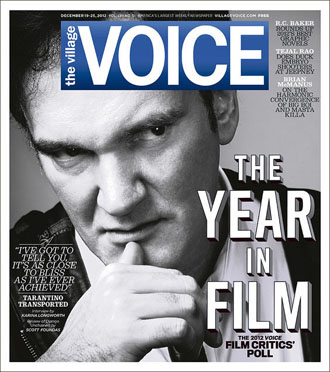

“There are few filmmakers I would agree to interview for a cover story without actually having seen their movie first: This year, the list starts and ends with Quentin Tarantino.” Karina Longworth‘s interview turns into a terrific profile, cover-ready for the Village Voice. And yes, eventually, she does see Django Unchained and finds that, “while it lacks a certain aesthetic panache (to borrow a word from Waltz’s character), the script and the performances place it among Tarantino’s richest works. On one level, there’s a lot riding on its performance: It cost more than $80 million, making it the priciest movie Tarantino has ever made. On the other hand, because Basterds was such a massive success, he’s got nothing to prove.”

Charles McGrath meets QT, too, for the New York Times: “He was dressed for the occasion like one of the characters in his first feature, Reservoir Dogs—white shirt, dark suit, dark tie loosened at the neck—but over lunch at Fiddlesticks, a West Village bar that is one of his hangouts, his affect was much less cool. He was unable to contain his enthusiasm for movies, his own and just about everyone else’s.”

“Listen To The Full ‘Django Unchained’ Soundtrack & Watch Over 12 Minutes Of Behind-The-Scenes B-Roll Footage.” If you’re up for all that, head to the Playlist, where you can also listen to Frank Ocean’s ballad, “Wise Man,” which didn’t make the final cut, and watch a trailer mashed up with Blazing Saddles.

And then there’s a gallery at Flavorwire: “30 Amazing Tattoos Inspired by Quentin Tarantino Films.”

Updates, 12/25: “What’s remarkable about Tarantino,” writes J. Hoberman at Artinfo, “both as a personality and an artist, is his capacity to be at once highly self-conscious and blithely devoid of self-awareness. Everything… is set in ‘Tarantino world.’ Each new release is heralded by a year or more of pre-publicity, followed by a round of interviews in which the writer-director enthusiastically discusses his particular sources and references, locates this latest movie’s place in his oeuvre (as well as movie history), elaborates on his methodology, reiterates his position on violence, and refines his theory of cinema.” Django Unchained “continues the relative maturity of Tarantino’s last movie in that it purports to be about something beyond its author’s fervent cinephilia…. It’s less successful in my view but not for want of trying.”

“As irritating, if not quite as inflammatory, as a hemorrhoid, Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained makes a queasy Oscar-season obverse not to Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, as some have suggested, but to Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty,” argues Melissa Anderson, wr