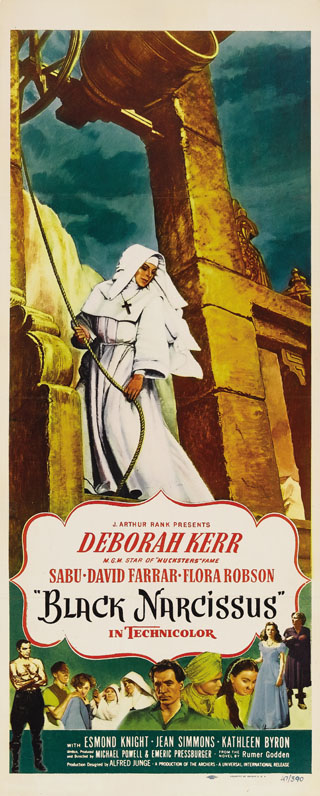

Always a good idea to begin with Kent Jones: “‘It is the most erotic film that I have ever made,’ wrote Michael Powell of Black Narcissus. ‘It is all done by suggestion, but eroticism is in every frame and image, from the beginning to the end.’ In his winningly grand manner, Powell was calling attention to what has become his 1947 masterpiece’s most oft-cited characteristic, and to its onetime selling point. In fact, the reduction of Black Narcissus by admirers and detractors (and cocreators!) alike to the three Es—expressionist, exotic (or, to get fancy about it, ‘exoticist’), and erotic—has often deprived this bracing film of its many nuances and complexities. It’s as if Jean Simmons’s seductive urchin and Kathleen Byron’s wanton Sister Ruth were the whole show. I don’t mean to imply that eroticism plays a less than crucial role—eroticism of place, of visual texture, and, most assuredly, of the flesh. But the film is also engaged with larger and more mysterious phenomena, which finally overshadow erotic desire. With great force, Black Narcissus addresses an enduring misconception: the longing, indeed fervent, belief that reality can be reconfigured to conform to an ideal image.”

That’s from an essay accompanying Criterion‘s Blu-ray release in 2010, which followed the 2001 DVD release. Just the other day, Criterion posted a gallery of on-the-set photos. And today, a new 4K digital restoration of Black Narcissus is opening its week-long run at New York’s Film Forum.

“The five nuns,” writes Keith Uhlich in Time Out New York, “led by the reserved Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), have their orders: Turn a remote Himalayan palace, once home to a king’s concubines, into a working convent that will minister to the local populace in body and spirit. That’s enough of a challenge, but there’s something truly unearthly about this place of howling winds, yawning chasms and atmosphere thick with temptation. Sanctity, it will be proven, is no match for sin. That great duo of stylized cinema, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, shot their classic dark-comic melodrama mostly on British studio sets, and the film’s very falseness—those matte-painting vanishing perspectives and cinematographer Jack Cardiff’s harshly exaggerated lighting cues—creates a psychologically charged space in which an ungodly tragedy can unfold.”

“If the fever-pitch conflict sounds quaint,” writes Benjamin Mercer in the L, “then perhaps it’s worth mentioning that Cristian Mungiu’s forthcoming convent drama Beyond the Hills expands upon (and complicates) many questions of desire and devotion raised by Black Narcissus; the 1947 film—which portrays twilight-of-colonialism outreach as a strong (and perhaps destructive-on-all-counts) intoxicant against a heightened soundstage-India backdrop—would also make a hell of a double feature with Miguel Gomes’s Tabu (also at Film Forum, through January 8).”

“The putative cynicism and psychological barbarism of Black Narcissus appears especially odd when considered as a follow-up to the superstitious, rural romance of I Know Where I’m Going! and the kaleidoscopic wartime mock-epic A Matter of Life and Death,” writes Joseph Jon Lanthier in Slant. “And yet the film’s cadence is unmistakably Archers-ian, perhaps by virtue of what juxtapositions with earlier works reveal: Never before had it been posited so smartly or artfully that gilded stairways to heaven are surrounded by cragged precipices to hell. And, true, the duo’s aesthetic success in the years leading up to 1947 often depended upon their tendency to transcend, and subtly detonate, the propagandist objectives of their studio-funded projects, but what fuels the trenchant poetry of Powell and Pressburger could never be mistaken for benign jingoism or high Tory tenderness—the political leanings of the auteurs notwithstanding.”

In 2009, C. Jerry Kutner, blogging for Bright Lights, noted “the many similarities to the climax of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo made almost a dozen years later—the moving camera P.O.V. shots, the nuns, the chapel, the vertiginous wooden staircase, the church bell that dominates the composition of the last few frames, and the suspense created when we realize that one or more of the characters… is about to fall from a very great height. Earlier in the film, the screen turns red to communicate the Byron character’s encroaching insanity, an effect that foreshadows Marnie.”

For more, see Adam Bagatavicius, who argues in Offscreen that, of all the Powell and Pressburger films, Black Narcissus “is perhaps most overtly infused with elements of horror and fantasy”; Karli Lukas in Senses of Cinema; and Michael Walker‘s essay for the Winter 1978/79 issue of Framework, posted at the Powell & Pressburger Pages.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.