The newsiest item of the day has to be Michael Cieply and Julie Bosman‘s story in the New York Times on Salinger, the book coming out on September 3 and the film opening on September 6, both featuring “detailed assertions that [J.D.] Salinger instructed his estate to publish at least five additional books—some of them entirely new, some extending past work—in a sequence that he intended to begin as early as 2015. The new books and stories were largely written before Mr. Salinger assigned his output to a trust in 2008, and would greatly expand the Salinger legacy.” Looks like we may soon be reading more about the Glass family, Holden Caufield, Hindu philosophy, World War II, and Salinger’s first marriage.

The second order of business that has to be seen to right away is a petition in support of the endangered Cinemateca Portuguesa (see yesterday’s update). However you personally rank the merits of cyberactivism, please do consider autotranslating, reading and signing it.

Reading. Today’s Observer is an issue that seems tailor-made for cinephiles. For starters, the paper is throwing a star-studded retirement party for its film critic of 50 years, Philip French, who’ll turn 80 in a few weeks. Elizabeth Day chats with him and finds that he “peppers his conversation with anecdotes about meeting Graham Greene and Jorge Luis Borges. In fact, French talks as he writes—eloquently, with absolute mastery of his subject and a startling degree of insight.” The Observer‘s been taking questions for French from the likes of Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, Joanna Hogg, and other readers.

There’s also an interactive guide to many of the best of French’s reviews—and then there are the tributes. From Martin Scorsese as well as from John Boorman, Danny Boyle, David Hare, Walter Hill, Hugh Hudson, Helena Kennedy, Lynda Myles, Nicolas Roeg, and Douglas Slocombe.

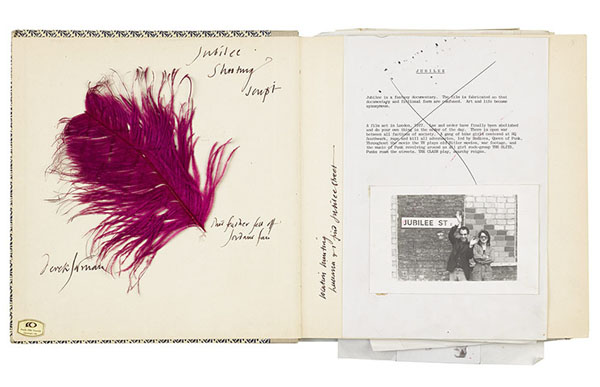

“‘There are so many different Derek Jarmans that it feels strange to focus on just one aspect of the man,’ writes pop culture historian Jon Savage in one of the many essays-cum-recollections threaded though the beautifully produced Derek Jarman’s Sketchbooks,” notes Sean O’Hagan. “And yet the ideas mapped out in the 31 private sketchbooks the controversial filmmaker, artist and gay activist produced throughout his working life are like blueprints for his many and varied projects, and show off a restless creative temperament that roamed far and wide for its inspiration.” And you can browse the Observer‘s collection of photos.

Christopher Bray finds that, for the most part, Nicolas Roeg’s memoir, The World Is Ever Changing, “does little more than prove that artists are rarely best placed to explicate their work. Roeg’s analyses of Don’t Look Now and Eureka make these magically allusive movies seem like moralistic potboilers. It’s all rather baffling. You don’t have to agree with Roeg’s highfalutin suggestion that cinema might ‘hold clues to realities even bigger than Einstein or Darwin’s theories’ to see that his own movies suggest what it might be like to pierce the Kantian phenomenon.”

“Is this script—which combines several of the most beautiful themes American cinema has had the pleasure of treating—not the best with which Hitchcock has ever worked?” Kino Slang‘s posted Ted Fendt‘s translation of Jacques Rivette‘s 1950 article on Under Capricorn (1949): “Theater is subject to the virtue of presence and the contagion of corporeal lyricism, cinema intellectualizes concrete givens through the sole distinction of the rigorous organization of time and space, irremediably linked and positioned.”

Stoffel Debuysere translates Jacques Rancière‘s 1998 piece for Cahiers du cinéma on Eisenstein: “He didn’t put the young cinematic art in the service of communism. He has rather put communism to the test of cinema, to the test of the idea of art and modernity of which cinema was, for him, the incarnation: that of a language of ideas becoming a language of sensation.”

“When Far from Vietnam came out in the United States in 1968, Renata Adler described its narration in the New York Times as ‘serene banality and ugliness,’ a judgment worth revisiting,” finds Ela Bittencourt, writing for Slant. “Spearheaded and edited by Chris Marker, this documentary essay, conceived as an outcry against the Vietnam War, is a collaboration between Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Jean-Luc Godard, William Klein, Joris Ivens, and Agnès Varda, though it was released without individual credits…. The voiceover’s forceful rhetoric is marked by Marker’s sardonic humor and quick turns of mind, such as when, in one section, comic-book characters serve to illustrate America’s overwhelming military might. Nevertheless, Adler’s criticism retains some currency.”

From the Los Angeles Review of Books, “Harlan Ellison Goes to Hollywood”

Profiling Al Pacino for Smithsonian Magazine, Ron Rosenbaum finds the actor struggling with a dilemma: “How is he going to present to the public his strange two-film version of the wild Oscar Wilde play called Salome? Is he finally ready to risk releasing the newest versions of his six-year-long ‘passion project,’ as the Hollywood cynics tend to call such risky business?”

Related: In January 2012, Megan Gambino spoke with Tom Santopietro for the magazine about his book, The Godfather Effect: Changing Hollywood, America, and Me, in which he argues that Coppola’s 1972 film “helped Italianize American culture.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.