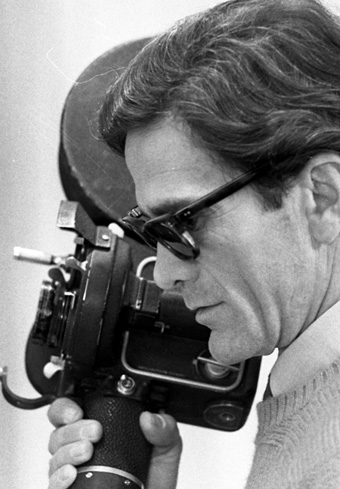

“More than two decades after its 1990 retrospective of Pier Paolo Pasolini, MoMA once again joins with Luce Cinecittà and Fondo Pier Paolo Pasolini/Cineteca di Bologna to present a full retrospective of Pasolini’s cinematic output.” So begins the Museum’s introduction to the program launching this evening with Medea (1969, with Maria Callas no less) and running through January 5.

In her overview of the series for Capital, Marion Lignan Rosenberg actually begins with the literary oeuvre: “In 1942, after studying art history, he published a collection of poems in Friulian dialect—a political act, since the suppression of regional dialects was a cornerstone of Mussolini’s cultural policy.” Then came the on-again, off-again relationship with the Italian Communist Party, the nearly three dozen run-ins with the law (“he was charged with corrupting minors and committing lewd public acts”), the persistent barrage of newspaper editorials, more poetry, literary criticism, and novels, most notably The Boys of Life (1955). Rosenberg:

Pasolini’s growing literary reputation brought him work as a screenwriter for Fellini and others. But frustrated with his scant creative control and hungry for what he called the ‘object-like concreteness of cinema,’ he took up directing himself and in 1961 released his first film, Accattone (The Scrounger). Like its creator, it is a bundle of contradictions. Featuring mostly non-professional actors, mixing dialect and standard Italian, and shot in Rome’s most impoverished areas, the film focuses on a pimp, Vittorio, nicknamed ‘Accattone.’ Once again, critics of all stripes lambasted Pasolini for depicting the hopeless, criminal urban poor—a class and a reality supposedly erased by Italy’s post-war economic boom.

And yet for all of Accattone‘s gritty themes, Pasolini repeatedly undermines the film’s “naturalism,” marking his distance from neorealist cinema and any mystifying intimations of unmediated truth. Music by Bach swells under the opening credits; a character mentions Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the first seconds of the action; and Pasolini’s meticulously composed shots, set sharply one after the other, eschew cinema’s fluid motion and recall the paintings of Masaccio, Mantegna, and other masters that he had studied in school. Ara H. Merjian, the author of a forthcoming book about Pasolini, has written that the “remove” of film, “which flattens and etherealizes flesh and bone into two-dimensional specters,” remained vital to the director’s work even as he proclaimed his “love for the ‘things’ of the world.”

For Twitch, Dustin Chang previews Accattone, Sopraluoghi in Palestina per il film Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (In Search of Locations for The Gospel According to Matthew, 1964), “an important companion piece to that austere masterpiece,” La terra vista dalla luna (The Earth as Seen from the Moon, 1966), Pasolini’s contribution to the omnibus film The Witches (the other directors are Mauro Bolognini, Vittorio De Sica, Franco Rossi, and Lucino Visconti), and Appunti per un’Orestiade Africana (Notes for an African Oresteia, 1970): “It’s too bad the film never actually happened.”

Sunday afternoon sees a program of multimedia presentations, Pier Paolo Pasolini: Intellettuale, presented by Paul Chan, Ninetto Davoli, Emi Fontana, Barbara Hammer, Alfredo Jaar, Lovett/Codagnone, and Fabio Mauri at MoMA PS1. Adds A.C. Lee in the New York Times: “The literary critic Harold Bloom is among those who consider Pasolini to be as important for his poetry as for his films. You can judge for yourself at MoMA’s main branch in Midtown on Friday night, when admission is free from 4 to 8 p.m. The poet Anne Waldman, the actress Annabella Sciorra and others will read from Pasolini’s work to music he composed.” And on Saturday, the exhibition Pier Paolo Pasolini: Portraits, Self Portraits opens at Location One.

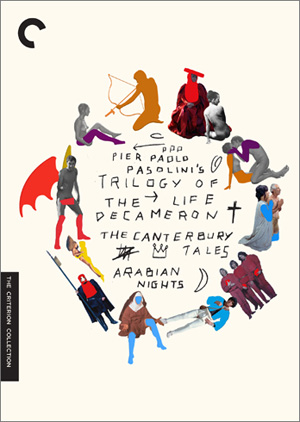

All this follows last month’s release of Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life on DVD and Blu-ray from Criterion, which has also run Colin MacCabe’s essays on each of the films: The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974).

Also definitely worth noting again are James Blue‘s 1965 interview with Pasolini for Film Comment, an interview filmed on the set of Salò (1975), and Celluloid Liberation Front‘s translation of Pasolini’s last interview, conducted three days before he was murdered in 1975, at MUBI’s Notebook.

Updates, 12/16: “It is no exaggeration to suggest that he is the most influential cultural figure in Italy since the Second World War,” writes Patrick Rumble in Artforum, “and his influence remains largely undiminished since his assassination in 1975—a crime still shrouded in mystery and often likened, by Italians, to the assassination of JFK (both in terms of its cultural significance and in acknowledgment of the multitudinous conspiracy theories that surround it)…. His was a persona that brought together three presumedly mutually exclusive identities, a persona that reflected the political and ideological fault lines and institutions that conditioned Italian social life: the Roman Catholic Church and the Christian Democratic Party that represents it, on the one hand, and the Communist Party, which emerged victorious from the Resistance and stood in opposition to the church, on the other. Being a Catholic Marxist was exceedingly difficult in the aftermath of the war in Italy; to be gay, as well, was all but unthinkable. It was perhaps this untenable combination of identities within Pasolini’s complex character that formed the matrix for his unorthodox approach to art and politics, resulting in a discomfiting and often scandalous body of work and leaving behind a legacy of radical questioning and intellectual vitality for the generations of filmmakers and artists who came after him.”

“Compared to the dreamy tales of Fellini or cool, modernistic alienation of Antonioni‘s films, Pasolini’s output possesses a less immediate appeal,” writes Celluloid Liberation Front at Indiewire. “His early films are coarse, irredeemable stories sculpted by the pain of marginal characters living on the fringes of a rapidly changing society. In both Accattone (1961), his debut, and Mamma Roma (1962), the Italian director observes the ordinary misery of social misfits but frames it with an almost religious eye. In the abjection of the defeated, Pasolini sees a sacred beauty and uses the symbols of Christian iconography to capture it. Considered by the director as the victims of progress and industrialization, the ‘untouchables’ of the Roman ghettos are his muses. But unlike the neo-realism of Rossellini, in Pasolini’s films (often acted by non professionals) there is no room for benevolence or happy endings; the cruelty of life always takes its toll.”

Update, 12/29: “The clearest thread running through Pasolini’s movies is his mounting disgust with the modern world,” writes Dennis Lim in the NYT. “He saw Italy’s postwar boom as an irreversible blight, turning the masses into mindless consumers and erasing local cultures. (For Pasolini difference was always to be protected and flaunted.) … While he has no equivalent in the contemporary landscape, Pasolini paved the way for many filmmakers, including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Derek Jarman, Gus Van Sant and Abel Ferrara (who has been planning a Pasolini biopic for years).”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.