“In Spike Jonze’s remarkable new film, Her, Los Angeles doesn’t play itself, and neither does love,” begins Slant‘s Ed Gonzalez. “A gene splice of America’s second largest city and Shanghai, the location of the film, like the clothes the story’s characters wear and the furniture that decorates their homes, suggests neither yesterday, today, nor tomorrow. Everything, including identity, has the feel of simulation. People here do not work between floors, like Craig Schwartz in Being John Malkovich, yet they’re still caught between spaces, psychic and otherwise, and if they don’t have to literally escape into fantasy worlds to cope with trauma, like Max in Where the Wild Things Are, it’s only because they live in a world where technology has so thoroughly mediated and shaped human interaction that their real lives are already the stuff of fantasy. Sound familiar?”

In his terrific profile of Jonze for New York, Mark Harris notes that “Her springs from a notion that could be played as rimshot contemporary satire: A sensitive, lonely guy (Joaquin Phoenix) coming off a rough divorce falls head over heels for a woman who’s literally custom-made for him—the artificially sentient female voice of his new computer operating system. But just as he did in Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, Jonze uses the gimmick to unlock a door to unsmirky human feeling. The result is not just a cautionary meditation on romance and technology but a subtle exploration of the weirdness, delusiveness, and one-sidedness of love. For all his imaginative conceits, Jonze is, in his way, a realist; he’s less interested in playing with the technologically extraordinary than he is in demonstrating the ways in which it can burrow into our most private selves.”

“The story evinces such empathy for its characters and respect for their emotions,” writes David Ehrlich at Film.com, “that the film never threatens to become a gawking sideshow that makes a spectacle of redeeming its hero (I’m looking at you, Lars and the Real Girl), and the movie’s premise seldom overwhelms its plot. Of course, in this day and age it would be harder to imagine someone who isn’t in love with their cell phone.” What’s more, Samantha, the OS, is voiced by Scarlett Johansson, “who doesn’t need a body to deliver one of the sexiest performances of the year.”

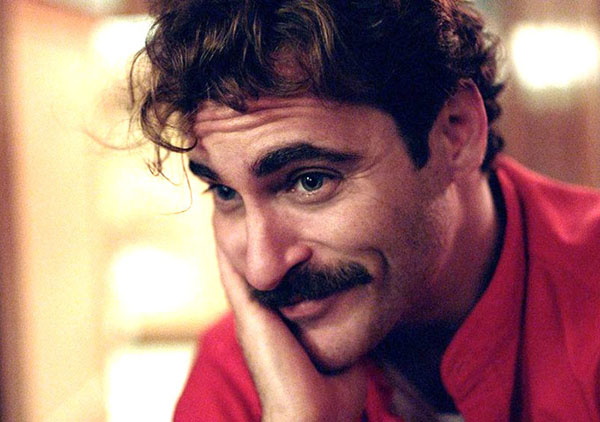

“If you were looking for an actor worth watching for a couple of hours in closeup talking cuddly-dreamy to a computer, you might not immediately think of Phoenix,” grants Time‘s Richard Corliss. “His bad-boy rep, shown grandly if fictionally in the mock-doc I’m Still Here, could blot out a viewer’s appreciation of his performance, no matter how persuasive. Yet Phoenix slips instantly into Theodore, corralling the dulcet melancholy of a man whose emotional pain finds refuge in Samantha’s embrace, in a love that, to misquote Phillip K. Dick, is ‘more human than human.’ Like Sandra Bullock in Gravity and Robert Redford in All Is Lost, Phoenix must communicate his movie’s meaning and feelings virtually on his own. That he does, with subtle grace and depth.”

Phoenix plays Theodore Twombly, “a former alt-weekly writer who now plies his trade as a latter-day Cyrano de Bergerac, penning other people’s love letters as a worker bee for the online service BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com,” explains Variety‘s Scott Foundas. “Laid low by a recent separation from his wife (Rooney Mara, seen mostly in staccato flashbacks), the divorce papers all but final, Theodore drifts about in a depressive haze, more adept at channeling strangers’ feelings than his own…. Jonze fleshes out Theodore’s world ever so slightly, with Chris Pratt as an affable office manager and Amy Adams as an old college chum and erstwhile paramour. But mostly Her is a two-(terabyte?)-hander of bracing intimacy, acutely capturing the feel of an intense affair in which the rest of the world seems to pass by at a distance. And where so many sci-fi movies overburden us with elaborate explanations of the new world order, Her keeps things airy and porous, feathering in a few concrete details (a news report mentions an impending merger between India and China) while leaving much to the viewer’s imagination.”

For Martin Tsai, writing in the Critic’s Notebook, “Her is wise and mature about relationships in a way reminiscent of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, [which Charlie] Kaufman wrote nearly a decade ago for Michel Gondry to direct. But Mr. Kaufman has since demonstrated, five years ago with Synecdoche, New York, that he’s evolved at a much faster pace.”

But for the Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy, the “theme and dramatic drive behind Jonze’s original screenplay, the search for love and the need to ‘only connect,’ is as old as time, but he embraces it in a speculative way that feels very pertinent to the moment and captures the emotional malaise of a future just an intriguing step or two ahead of contemporary reality.”

“Certainly his most deeply felt achievement, Her is both distinctly Jonze-like and something altogether different, as if the filmmaker has gone through a software update not unlike his artificial character,” writes Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn.

“Lensed with comforting, warm pastels, director of cinematography Hoyte van Hoytema (The Fighter, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy) has a keen eye for the movie’s soft emotional temperature,” writes Rodrigo Perez at the Playlist. “His camera, while intimate, is never disruptive. The film’s music—a gorgeous, wistful mix of melancholia and hopefulness—is bisected: the score is composed by the Arcade Fire and fellow AF collaborator Owen Pallet also contributed, but to all of the musicians’ credit, the various dreamy timbres are very much like a unified holistic piece (and it’s surely one you’ll be setting to repeat on your iPod in the months to come).”

Lacing her review with quotes from Spike Jonze’s onstage conversation with Kelly Reichardt in Toronto, Anne Thompson calls Her “a well-constructed, engaging narrative.”

“I think it’s officially my favorite American film of 2013,” declares Jose Solis at the Film Experience.

Chris Michael interviews Jonze for the Guardian, while Darren Aronofsky talks with Johansson for Interview. Her premiered on Saturday as the closing night presentation at the New York Film Festival.

Updates, 10/14: “Perhaps the most crucial element of Jonze’s vision,” writes Kenji Fujishima at the House Next Door, “is its sympathetic embrace of the volatile beating hearts of its characters. This is no bleak dystopia where the machines have already taken over before the movie has even started; the characters here are distinct individuals with fundamental human desires—for love, for stability, and so on—that technology is theoretically poised to address and maybe even satisfy. In other words, Jonze provides a recognizable emotional context within this futuristic world, with his characters—from Theodore to minor ones such as his longtime friend, Amy (Amy Adams), and Olivia Wilde’s unnamed blind date and a sex surrogate (Portia Doubleday)—experiencing moments of joy, yearning, and melancholy that feel true every step of the way.”

“In movies like Adaptation and Being John Malkovich, Jonze went madcap and meta in the third act, something that could derail a more delicate human story,” writes Steven Zeitchik in the Los Angeles Times. “At the same time, crafting too grounded a story could undermine what makes it a Jonze pic in the first place. Yet Jonze, who directed Her from his own screenplay, manages to do both here, the emo and the wild whimsy all kept in nice balance.”

Her is one of the films Peter Labuza and Tony Dayoub discuss in the latest Cinephiliacs podcast.

Updates, 10/15: Reviewing Her for the Guardian, Tom Shone finds that “the film is half in love with the loneliness it diagnoses. The whole thing looks like the most expensive ad for urban anomie ever made—Antonioni for the artisanal-cheese set—and for the first hour the conceit is unveiled beautifully, via a brisk series of gags, most of them in the periphery of the main plot…. The closer we draw to the central romance, the straighter grows the film’s face.”

“Jonze can’t fully avoid the usual tropes—the depiction of social awkwardness is more Garden State than Playtime—but the film plays beautifully despite the congenital silliness of its concept.” Steve Macfarlane at the L: “Her doesn’t quite hit all its marks, but honorably keeps its questions open from start to finish, its vernacular queasily swerving from the most twee Apple commercial ever made to a thorough treatise on human isolation and emotional repression without losing any of its color.”

Flavorwire‘s Jason Bailey: “Anchoring the film is Phoenix’s raw, open work, yet another in his string of eccentric yet painfully honest performances, one all the more impressive in that he plays most of his scenes technically alone, with long scenes, often long takes, where the camera is just holding on his face. And we don’t blink.”

At Twitch, Dustin Chang predicts that Her is “bound to be a cult classic.” For Katie Calautti, writing at Movies.com, it’s “a prescient, funny, wrenching glimpse at how we court loneliness in our efforts to chase it away.”

“Jonze has made a dystopia of gentrification,” argues Bryce J. Renninger at Indiewire. Even though Her is set in the Los Angeles of the near future, “there don’t seem to be any Latino people in the whole damn film.”

Update, 10/23: “Her is the first of Jonze’s films to wear its heart more or less on its sleeve, unfiltered through any source texts or self-referential meta devices,” writes Max Nelson at Reverse Shot. “It might also be the first of his films to rely heavily on the context of the moment in which it was made, which makes it much harder to evaluate with any perspective. Once we get some distance from the movie’s fears about the effect of technology on human relationships, we might be able to say with greater confidence how well Jonze understands people—or, for that matter, relationships.”

Update, 11/5: Logan Hill talks with Jonze for the NYT.

Update, 11/16: Her “is a relationship drama that’s complicated, meaty, and challenging in its implications,” writes Sarah Mankoff in Film Comment. “Theodore and Samantha’s problems are normal—affections don’t always align, or the two project too much onto each other—and singular: for instance, the fact that Samantha has no physical body. When Rooney Mara makes a sharp appearance as Theo’s ex-wife, her incredulousness at his inability to date a real woman is both a relief and off base. Her is told from Theo’s perspective, and all he can ever really know about Samantha is that she’s infinite—and when it comes to another person, what’s more real than that?”

Update, 11/19: “The strength of Her is, as the title suggests, that it doesn’t matter who the woman is,” writes Kaleem Aftab for Filmmaker. “Theodore is just unable to cope with the opposite sex. He can wear a cool 1920s wardrobe, although the high waists are not as flattering as the bright colors on Phoenix’s frame, but there is an objectifying of women and a desire for the gender to live up to his own (impossible) desires. So it’s no surprise then that the only woman capable of doing that is his fantasy. The weakness is that everything is on point. Theodore’s job, his relationships, his friends’ relationships, the jokes about liberal lifestyle; Jonze doesn’t really say anything new, or anything that he hasn’t said before, and with more verve, in his music videos, Being John Malkovich or Adaptation.”

Updates, 12/1: Here in Keyframe, Sara Maria Vizcarrondo looks at the ways Jonze and his former wife, Sofia Coppola, treat divorce in Her and Lost in Translation (2003).

“Sadly, Her is destined to date like imported fruit,” argues Michael Atkinson at Sundance Now. “Watch: it’ll rise on Top Ten lists this December, and then in a few years nobody will even remember it exists. It’s a melancholy, lonely little film, and I’m starting to feel seriously sad for it… But maybe Jonze designed Her to have exactly this kind of fate—to be as ephemeral and replaceable as the social gadgetry at the film’s center…. Since the film itself constitutes a piece of ‘personal’ technology, likely to be viewed on soon-to-be-obsolete screens, what would be savvier than to fashion it so that it immediately slipped from our grasp?”

John Patterson interviews Jonze for the Guardian.

Update, 12/6: “Her is so obsessed with trying to tell a story about ‘how we live now’ that any of its profound ideas seem quite self-evident,” argues Peter Labuza. Several “sequences rely on montages that could come out of his 90s music videos—pleasantly shot in mutedly light colors for pleasant compositions, but rarely perceptive ones—pandering to a little more than a cinematic equivalent of BuzzFeed. It’s an emotional simulacrum without depth.”

Updates, 12/20: For Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, writing in the Notebook, “despite all of its retro-futuristic bric-a-brac and next-phase-of-Western-culture guesswork, the impressive thing about Her is its simplicity and sensitivity. Composed in large part of long, locked-in close-ups, the movie is as much—if not more—about regarding and exploring the muscles and movements of the face as it is about hedging the future…. In the end, Her is both a transhumanist love story and a stridently humanist one—not a paradox, but something that gently nudges at the complex and contradictory nature of romance.”

“What makes Her so potent is that it does to us what Samantha does to Theodore,” writes Anthony Lane. “We are informed, cosseted, and entertained, and yet we are never more than a breath away from being creeped out. Just because someone browses your correspondence in a mood of flirtatious bonhomie doesn’t make her any less invasive; and just because you have invited her to do so doesn’t mean that you are in control. Who would have guessed, after a year of headlines about the N.S.A. and about the porousness of life online, that our worries on that score—not so much the political unease as a basic ontological fear that our inmost self is possibly up for grabs—would be best enshrined in a weird little romance by the man who made Being John Malkovich and Where the Wild Things Are?”

In the opposite corner, and yet also writing for the New Yorker, Richard Brody: “Her is a cautionary tale that offers warning where none is needed, a diffuse and sentimental admonition to put the smartphone down, push away from the computer, turn off the TV, unplug the game controller, and connect with people. But when people do attempt to connect, Jonze (who also wrote the script) endows them with nothing but psychobabbulous clichés to define themselves. The film, with its dewy tone and gentle manners, plays like a feature-length kitten video, leaving viewers to coo at the cute humans who live like pets in a world-scale safe house.”

“There are whole chunks of Her, so arduously layered with soft-focus pain and cautious happiness, that could have been lifted from those ’80s phone commercials touting the benefits of ‘staying connected,'” agrees Stephanie Zacharek in the Voice. “Theodore, like James Stewart in Vertigo, is in love with an illusion. The difference is that this spectacle and all its ideas would fit on the screen of your iPod.”

“It’s a perfect tale for Mr. Jonze, a fabulist whose sense of the absurd informs his more broadly comic endeavors (notably his work on the Jackass movies, including Bad Grandpa) and the straighter if still kinked art-house films he’s directed,” finds the New York Times‘ Manohla Dargis. “If it has taken time for the depth of Mr. Jonze’s talents to be recognized, it’s partly because of all the attention bestowed on Charlie Kaufman’s scripts for Adaptation and John Malkovich, which announce their auteurist aspirations on the page…. There are times when Her has the quality of a private dispatch, like a secret Mr. Jonze is whispering in your ear.”

For Melissa Anderson, writing for Artforum, Her “is neither a simple lamentation about our overly mediated lives nor a gooey exploration of loneliness, but a perceptive reflection on the need for—and folly of—attachment.”

Her “evokes the most convincing same-but-different future city since the sketchily glimpsed one in Soderbergh’s Solaris,” writes Jonathan Romney for Film Comment. “What’s so entrancing about Her, however, is that it doesn’t offer a Terrible Warning—we’re far too used to them—but expresses its future vision as a seductive comic conceit. This elegant, moving entertainment is richer and more adult than you might have expected Spike Jonze to come up with.”

Her “plays like a kind of miracle the first time around,” writes Glenn Kenny at RogerEbert.com. “If there’s a ‘but,’ it’s that the movie can sometimes seem a little too pleased with itself, its sincerity sometimes communicating a slightly holier-than-thou preciosity.” Still, “Her remains one of the most engaging and genuinely provocative movies you’re likely to see this year, and definitely a challenging but not inapt date movie.”

Slate‘s Dana Stevens: “Her isn’t, in the end, a political or socio-cultural satire, much less a nostalgic tract about the need to throw away our devices and truly live. It’s a wistful portrait of our current love affair with technology in all its promise and disappointment, a post-human Annie Hall.”

Scott Tobias at the Dissolve: “As much an open wound here as he was in The Master, Phoenix makes Theodore’s relationship with Samantha seem credible—in part because his character is antisocial, in part because he’s so good at playing the type of restless seeker who will look for enlightenment wherever he can find it. But Johansson is the real revelation here: Using only the disembodied voice of one of the world’s premier sex symbols is the very definition of counterintuitive, but Johansson’s voice is flinty and seductive, suggesting a form where none exists.”

“The movie itself must have taken Jonze to places he didn’t expect,” suggests New York‘s David Edelstein. At the AV Club, A.A. Dowd writes: “Whether Jonze built Her from his own history or invented it from scratch, it feels like a direct portal into his beating, bleeding heart.”

Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir asks, “can we just agree to give Amy Adams all the acting awards and move on from there?” At the Daily Beast, Marlow Stern argues that Phoenix is the “greatest actor alive right now.”

More from Michelle Dean (Flavorwire), Steve Erickson (Gay City News), David Fear (Time Out New York, 4/5), Christopher Orr (New Republic), Jordan M. Smith (Ioncinema, 4.5/5), and Jessica Winter (Slate).

“While the sci-fi romance is singular as a feature,” writes Forrest Wickman for Slate, “its unusual setting—call it the uncanny valley—is not new territory for Jonze: He has been exploring it for years in all his best shorts.” And he posts five.

Interviews with Jonze: Nigel M. Smith (Indiewire) and Rodrigo Perez (Playlist). For The Credits, Bryan Abrams talks with production designer K.K. Barrett.

Update, 12/23: “In a column in the New York Times, Frank Bruni called Her ‘a parable of narcissism in the digital world,'” notes John Semley, writing for Esquire. “I think this misses the point. For sure, the film is a sort of techno-psychological inkblot test, revealing a given viewer’s particular relationship to technology. But it doesn’t seem all that concerned with hand-wringing over old-hat stuff like technology and alienation and how social media has turned us inside of ourselves. Jonze knows better than to think that just because emotions—even whole identities—are mediated or displaced doesn’t mean they’re any less real or meaningful.”

Updates, 12/25: “Jonze never makes Theodore an object of pity or scorn,” writes Max Nelson for Film Comment. “His romance with the disembodied Samantha is as real as, if not realer than, any of the film’s human relationships: like all of Her’s dialogue, their conversations are just fluid and articulate enough to sound natural, and just clumsy enough to sound spontaneous. Credit also goes to Phoenix, playing a sensitive, puppy-doggish, caterpillar-mustached romantic whose day job consists of writing intimate letters on behalf of anonymous clients. Like many Phoenix characters, he seems a little off balance, physically and mentally, as if he’s perpetually on the brink of an eruption of violent self-loathing.”

Ray Pride at Newcity Film: “The conceit sounds awful from outside, but inside Her, it’s supertragicmagicdelicious: writer-director Spike Jonze really, really makes it work…. By exquisite extension, Jonze builds on the feigned intimacy of software and social media sentiment that presently exists, a kind of lucid dreaming of the near future, but also of the dangers of not knowing the difference between fantasy and what is right at hand.”

“Fear about separation has been central to the success of Jonze’s first films,” writes Christine Smallwood in a piece for the New Yorker laced with spoilers. “It’s what gave them a layer of tenderness, vulnerability, and