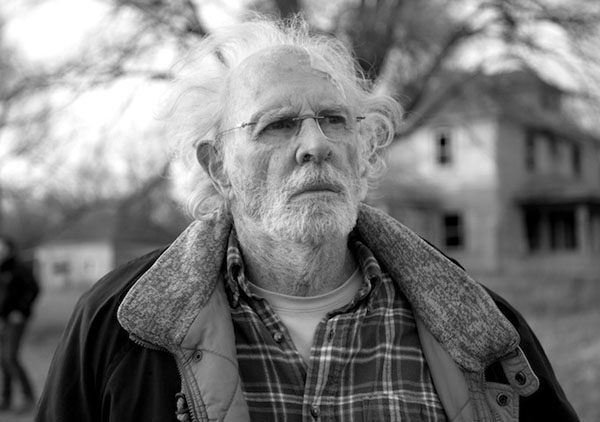

In Alexander Payne’s Nebraska, “Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) isn’t quite senile,” writes Jesse Hassenger at the L, “but he isn’t quite in the frame of mind that would keep him from setting off from Billings, Montana, to Lincoln, Nebraska, on foot, convinced he’s won a Publisher’s Clearinghouse-style sweepstakes prize. His frustrated son David (Will Forte) agrees to drive him to collect his winnings, even though he doesn’t believe it for a second. Payne has been kicking around Bob Nelson’s extremely Payne-y screenplay for the past 10 years, reluctant to follow Sideways with another road movie. But Nebraska is much more of a hometown-return movie than a real road-trip picture; Woody and David wind up stopping for a weekend in Hawthorne, Nebraska, where David was born. They meet up with family, wander around (‘Let’s see if I know anyone in here’ is one of the more elaborate plans the taciturn Woody makes), and both encourage and deflect talk of Woody’s supposed financial reward. Dern makes a surprisingly complex old coot: a man who growls and grouses but also appears defeated by his modest life. Forte, known for his sketch-comedy commitment, nicely underplays the son threatened by the specter of a similarly average life.”

At Slant, R. Kurt Osenlund finds that “the filmmaker’s overview of America is extraordinarily, multifariously profound. His mere perception of American iconography, and how its value echoes and evolves through generations, has a walloping impact. Already quaint and outdated, the signage of hotels, cafés, and gas stations fills Payne’s visual palette, and it’s regarded with more awe and reverence than a farm field or Mount Rushmore, which are criticized and de-romanticized by Woody, and, by extension, the film itself. It doesn’t take too long to realize that Woody’s certificate is the MacGuffin in not so much a family-bonding tale, but a capitalist fantasy. And as Hawthorne begins to unleash both vultures and well-wishers alike, including Woody’s bullying, lecherous former co-worker (Stacy Keach), and his tender, heartbreaking ex-girlfriend (Peg Nagy), all seem less interested in a piece of the man’s pie than the staunch assurance that the pie exists.”

Nebraska‘s screening in London, and at the Arts Desk, Emma Simmonds finds that June Squibb, who plays Woody’s wife, “is particularly good value as the fabulously potty-mouthed Kate, whose salty tongue spices up an otherwise rather gentle film.” Time Out London‘s Dave Calhoun finds that the “film’s laughs are as low-key as Payne’s reflective but straight-shooting style of storytelling. Some time back, we noted that Larry Gross argues in Film Comment that Nebraska is “Payne’s best, most complex, and most satisfying work to date.”

David Ehrlich talks with Payne for Film.com and, for New York, Mary Kaye Schilling profiles Dern, who’s “starred—though mostly co-starred—in roughly 80 films and countless TV shows, particularly Westerns early on, often playing seriously deranged individuals; he’s tried to blow up the Super Bowl (1977’s Black Sunday), shot John Wayne in the back (1972’s The Cowboys), and done all manner of nasty polygamist shit on HBO’s Big Love. It’s something to do with that voice and face—the icy-blue eyes and wolfish grin—but also with the way he slides into the meanest line. ‘Bruce has the power of using excessive politeness to disguise malevolence,’ says his three-time director Walter Hill. ‘He’s always fun to watch, even in those lousy movies in the sixties. He’s never tried to steal a scene. But even when he’s underplaying it, as he does in Nebraska, he seizes and dominates the scene. The camera loves him in a very certain way—not the way it loves everybody, and Brucie’s aware of that. He knows his skills.'”

Earlier: Reviews from Cannes. The New York Film Festival‘s second and final screening of Nebraska happens today at noon sharp.

Update, 10/13: Oliver Lyttelton, dispatching to the Playlist from London: “Payne’s work has only become more popular over time (The Descendants was lauded with awards, and was his biggest hit to date), so I’m in the minority when I say that I think that Payne’s the rare filmmaker whose work has become less interesting with each film he makes. Over the years, the savage wit and sharp satire that marked Citizen Ruth and Election out as special pieces of work has been civilized and blunted, giving way to a forced, unearned sentiment present both in his previous film and this one.”

Update, 10/14: Nebraska is one of six films Peter Labuza and Tony Dayoub discuss in the latest Cinephiliacs podcast.

Update, 10/23: “Mr. Payne has already achieved a betting average rivaling Pixar’s,” writes Martin Tsai in the Critic’s Notebook, “but here he has finally established himself as a visionary. Phedon Papamichael’s lens work perfectly illustrates the languid mood, elevating Mr. Payne’s intimate humanist drama to an auteurist high.”

Updates, 11/11: For the New Yorker‘s David Denby, “the absurdist atmosphere feels thin: the movie is like a Beckett play without the metaphysical unease, the flickering blasphemies and revelations…. Dern delivers an affronted glare and an outraged assertiveness, but he has nothing to reveal, and Woody remains unfathomable…. It’s true that some fading people never come back into focus, no matter how much loving attention they receive, but making such a character the protagonist of a movie may be a well-intentioned mistake.”

“Payne seems to have done everything possible to shoot the tires on his own car,” grants New York‘s David Edelstein. “It turns out, though, that the point where so many of us squirm is Payne’s artistic sweet spot: the famously fine line between love and hate, empathy and ridicule. Nebraska is a bumpy ride—I fought with it constantly. But that car goes somewhere unexpected. The movie is a triumph of an especially satisfying kind. It arrives at a kind of gnarled grace that’s true to this sorry old man and the family he let down in so many ways.”

Logan Hill profiles Dern for the New York Times.

Updates, 11/15: Nebraska is “Payne’s best movie since his Jack Nicholson road movie About Schmidt,” declares J. Hoberman at Artinfo, “and, in its absence of grandstanding, perhaps better than that…. Nebraska’s rhythms may be as comfortable and creaky as an old rocking chair but there’s an edge to Payne’s nostalgia in that the movie’s old-fashioned virtues were, once upon a time, rigorously au currant. The 77-year-old Dern, who won the best acting award last May in Cannes, was a near axiom of the Hollywood new wave and Nebraska is something of a ’70s, BBS-style movie made today, with intimations of The Last Picture Show, The King of Marvin Gardens, and John Huston’s new wave loser flick, Fat City.”

“The chilling implication of this film is not that the old values of hard work, family and community have fallen away,” writes A.O. Scott in the New York Times, “but that they were never really there to begin with. Yet somehow the feeling that lingers after the last shot is the opposite of despair. If you listen to Nebraska all the way through, you will come away with this thought: At the end of every hard-earned day, people find some reason to believe.”

“Nebraska, despite a few pleasures, strikes me as Payne’s most cartoonish, one-dimensional work,” writes Melissa Anderson for Artforum.

“There’s a febrile artifice to Payne’s setup,” finds the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody, “and a tinge of theatrical exaggeration in the performances (including those of Dern and Forte) that contrast somewhat gratingly with the silky, painterly widescreen black-and-white images—and that very abrasion is the stuff of the movie. In effect, the contact with the rugged new environments (and that ruggedness is as much physical as it is emotional) does two things at once: it scrapes beneath the surfaces of those places to yield unanticipated and revealing layers of personal and family history, and it scrapes the paint off the personae and breaks through their social roles and set behavior to an unsought and uneasy vulnerability.”

More from Ryland Aldrich (Twitch), Ela Bittencourt (frieze), A.A. Dowd (AV Club, C+), David Fear (Time Out New York, 3/5), Richard Lawson (Atlantic Wire), Christy Lemire (RogerEbert.com, 3.5/4), Amy Nicholson (Voice), Andrew O’Hehir (Salon), Nicolas Rapold (L), Dana Stevens (Slate), and Scott Tobias (Dissolve, 4.5/5).

Payne talks a bit about the film for the NYT (1’30”). Interviews with Dern: Nathan Rabin (Dissolve) and Nigel M. Smith (Indiewire). And with Forte: Erik Adams (AV Club), Jake Mulligan (Slant), and Drew Taylor (Playlist).

Update, 11/18: At the Dissolve, Nathan Rabin, Tasha Robinson, and Scott Tobias discuss Payne’s work, with, of course, a focus on Nebraska.

Updates, 11/20: “I promise you, it contains multitudes,” writes Bob Odenkirk. “I hope you’ve heard that it’s funny. It’s funny. The kind of human comedy that makes Hal Ashby films always relevant (let’s be honest—Alexander is his most direct artistic descendant)…. I won’t spoil it for you, but while my character, Ross, a local newscaster and a striving egotist, and his brother, David, are diametrically opposed on how to handle their father’s loosening grip on reality, they partner up in a foolhardy plan to steal some farm equipment from that damn Ed Pegram! Crime! Narrow escapes! This film’s got it all.”

“What I come back to is the deep core of emotion in Nebraska,” writes Susanna Locascio at Hammer to Nail. “Woody is an easy target, and Payne deliberately fills his film with similar targets, especially the anemic small town of the heartland, with its small dramas and desires. But in its heart, Nebraska is a tribute.”

Dennis Harvey in the San Francisco Bay Guardian: “Nebraska has no moments so funny or dramatic they’d look outstanding in excerpt; low-key as they were, 2009’s Sideways and 2011’s The Descendants had bigger set pieces and narrative stakes. But like those movies, this one just ambles along until you realize you’re completely hooked, all positive emotional responses on full alert. There are minor things to quibble about…, but so much that’s so deeply satisfying you hardly want to get out of your seat at the end.”

Payne in Esquire: “I always have hope for American cinema, because I’m having the career I would like to have. And if it’s true as Spielberg and Lucas said earlier this year that the old tentpole formula may be collapsing, then it’s like old wood falling in a forest: Trees go away and that gives a chance for new trees to spring up. I always believe in movies.”

Allan Tong talks with Payne for Filmmaker, while Jason Guerrasio interviews Forte for Vanity Fair.

Updates, 11/22: “Payne is one of America’s quiet and persistent treasures,” writes David Thomson in the New Republic.

Nebraska‘s “an immensely satisfying adult comedy and one of Payne’s best,” writes Jonathan Romney for Film Comment. It comes laden with echoes of cinema’s color-era black-and-white landscape tradition—The Last Picture Show most obviously, not to mention Wenders’s Kings of the Road, which was nothing if not a search for America in the middle of Germany. But the closest comparison is surely Aki Kaurismäki’s 1994 film Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana, hitherto the most dour road comedy ever made, and another story about two emotionally illiterate men obliged to keep company in an inhospitable terrain. Some may feel that the sheer classiness of Papamichael’s photography is out of proportion to the modesty of the subject, but not only does it give Nebraska a dour elegance that lifts the story out of the realm of mere anecdote, it also makes you feel you’ve really been to these places—and perhaps relieved not to have made the trip in person.”

Update, 12/1: “Most of what’s good in Nebraska is also fairly obvious,” writes Adam Nayman for Cinema Scope. “Any praise it has received specifically for its subtlety has more to do with how skillfully Payne and his collaborators have applied a patina of subtlety—a good paint job—to the proceedings rather than any truly multifarious artistry. That’s not a knock, by the way… That the moment when Woody admits that he only went chasing after a jackpot so that he’d have something, anything, to leave to his kids after a lifetime spent steadily losing everything he worked for feels so methodically blueprinted does little to diminish its genuine melancholy. Reader, I cried.”

Updates, 12/6: The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw: “Classic Payne themes are restated: male sadness and disappointment with life, tempered with a sweeter, subsequent realization that these vanities are irrelevant.”

Bruce Dern’s a guest on the Leonard Lopate Show.

Update, 12/7: “For a filmmaker who’s been acclaimed for achieving a novelistic sense of psychological richness, often adapting literary sources and using voiceover to spell out the characters’ feelings, [Nebraska‘s] very spareness feels like a new chapter,” writes Trevor Johnston for Sight & Sound. “Overall, this intimate, insightful character study is affectingly true to itself, a heartening sign that a major American filmmaker is on confident form as he develops and deepens his craft.”

Updates, 12/25: “In Nebraska, Payne revisits The Descendants’ circle-of-life ruminations but reimagines them in a social and political context,” writes Elbert Ventura in Reverse Shot. “This American anthem abounds in signifiers of national identity: Big Sky expanses of farmland, highways as far as the eye can see, a final promenade down Main Street. The presence of Mt. Rushmore and ‘Woodrow Grant’ invoke at least half a dozen presidents; the name itself seems a deliberate allusion to Grant Wood, that iconic artist of the heartland. What transpires on this canvas amounts to a state of the union.” And it turns out that Woody “wanted the money so badly, he says, not because he wanted a new truck, as he’s been telling everyone, but because he has little to leave his boys when he’s gone. It is, in the wake of the Great Recession, nothing less than a national lament.”

“After a career of going off the rails,” writes Josef Braun, it’s “fascinating and strangely moving to see Dern reach this autumnal triumph.”

“In a movie that sinks too comfortably into glib assumptions about rural mores, failed fathers and sputtering marriages,” writes Scott Wilson in the Nashville Scene, June Squibb is “alert to the script’s few available chances to surprise. And she helps Dern’s fine performance seem like more than this movie allows it to be.”

Update, 1/7: Vulture‘s Kyle Buchanan talks with Bob Nelson about the toughest scene he wrote.

Update, 1/19:

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.