“Flight is Robert Zemeckis’s grand return to the land of the living,” begins David Ehrlich at Movies.com. “He’s a filmmaker beloved for modern classics like Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, but this is his first live-action feature since he 2000, when he decided to swan-dive directly into the deepest trenches of the Uncanny Valley (a plunge that resulted in The Polar Express, Beowulf, and that movie about a twisted dystopia in which almost every human is a mutated version of Jim Carrey). To some extent, Flight picks up where Cast Away left off, as Zemeckis arrives back in the tactile world with another character-driven drama about a man who survives a dramatic (and horrifyingly visceral) plane crash—the big difference here is that Zemeckis puts us with a pilot as opposed to a passenger, introducing Whip Whitaker as a man so isolated by his troubles that he may as well have spent his entire adult life alone on a deserted island.”

“Basically, it’s The High and the Mighty with a drug test,” suggests the New York Post‘s Lou Lumenick: “imagine if, after saving a planeload of passengers, John Wayne’s character in William Wellman‘s classic was found afterwards to not only having been flying while legally drunk, but snorted cocaine to steady his hung-over nerves before the flight.”

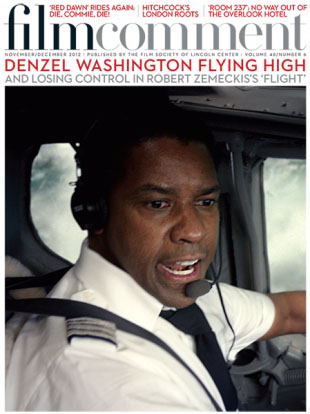

“A gritty, full-bodied character study about a man whose most exceptional deed may, ironically, have resulted from his most flagrant flaw, this absorbing drama provides Denzel Washington with one of his meatiest, most complex roles,” writes Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “Onscreen for nearly the entire running time, Washington has found one of the best parts of his career in Whip Whitaker, a middle-age pilot for a regional Southern airline who knows his stuff and can still get away with behaving half his age.”

“Few events are more visceral to experience onscreen than an airplane crash,” writes Variety‘s Peter Debruge, “and Flight ranks alongside Fearless and Alive in the sheer intensity of its opening act. But John Gatins’s perceptively original script takes the rest of the story in a far different direction.”

“It may have elements of action filmmaking and courtroom drama,” writes In Contention‘s Kristopher Tapley, “but it is, ultimately, a character study about the sickness of addiction. It captures the embarrassment, the denial, the rage and, crucially, the chronic fallibility that comes with it.”

Rodrigo Perez finds that Flight “is often undone by its very unsubtle choices and its problematic, strained last act.” At the Playlist, he gives it a B.

“The premise is already rich with allegorical and otherwise dramatic possibility, and is aided by several stellar performances, so when Zemeckis resorts to worn-out conceits, the film’s impact is significantly softened,” finds Ted Pigeon, writing at the House Next Door. “That Flight happily dwells within conventional boundaries can be frustrating given the raw and affecting potential of the material. But in its most effective passages, those in which Zemeckis is less self-conscious about making sure we grasping his allusions (to God, fate, etc.), Flight conjures stirring images that cut into the relationship of technological destruction and ‘human brokenness,’ as the filmmaker put in a post-screening press conference. For a director that has spent much of his career fashioning new uses of technology in film, sometimes with disastrous results, it’s perhaps no surprise that when he worries less about communicating big ideas, a beautiful thing can happen on the screen.”

Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn draws parallels between Flight, which has closed the 50th anniversary edition of the New York Film Festival, and Ang Lee’s Life of Pi, the film that opened it, noting that both “directly invoke religion… But where Life of Pi celebrates the possibilities of faith in a higher authority, Flight sublimates its dogma into a shrewd narrative about surviving addiction and coming to grips with the imperfections of human behavior…. The movie is notably not about the crash but rather the transformative power of a single cataclysmic event. For obvious reasons, Flight has post-9/11 demons in its DNA, but reflects the temperament of the current era to make peace with darkness and soldier forward to a better tomorrow. That’s an undeniably cheeky takeaway rendered in somewhat distractingly obvious terms with an overly familiar tell-all monologue in its concluding moments. But there’s nevertheless a welcome form of comfort that can be derived from its blatant sentimentalism. Viewed in the context of the festival, Flight epitomizes a dogged willingness to convey hope for the future while acknowledging the possibility of more dark days ahead. It’s a good way to go out.”

At Thompson on Hollywood, Sheerly Avni has video from the press conference, noting that Washington arrived late: “The audience didn’t mind of course, because he’s Denzel.” Also: “In 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, Washington had more chemistry with [Don] Cheadle than with any of his nubile love interests before or since, and almost 20 years later, nothing about that chemistry has changed. The few short scenes the two actors share give hints of how crackling Flight could have been if it had toned down its leaden redemptive beats.”

Updates, 10/16: “Whip grumbles at the daily services held by the nearby Pentecostal Church at the accident site, unambiguously depicted as a comically tasteless, self-aggrandizing response to tragedy,” writes Vadim Rizov for Box Office. “‘What kind of God would allow this to happen?’ he fumes. In his impatient secularism, Whip’s a descendant of Contact‘s Ellie Arroway, whose lack of belief nearly led to her disqualification from a space voyage. Intentionally or not, Zemeckis has now directed two of the more explicit defenses of atheism in Hollywood history, while granting believers a charitable portrayal: Matthew McConaughey as a Christian philosopher in Contact, and here, the maternal flight attendant Margaret (Tamara Tunie), who disapprovingly covers for him…. Still, both flicks end apologetically: Contact with fuzzy New Age spirituality, and Flight with Whip implicitly recognizing the ‘higher power’ AA enrollees are encouraged to rely upon.”

“Contact basically asked if an extraordinary person was excused for personal failings if it turned out they were right,” notes HitFix‘s Drew McWeeney, “and Flight asks if being exceptional at one thing is enough to justify an almost total failing as a human being in other regards. Zemeckis seems drawn to the notion of people who are gifted and driven but who are unable to handle even the basic rules of social conduct.”

“Flight is a star vehicle, rolled and inverted just like that plane,” writes Tom Shone for the Guardian, “but then Washington is probably the only star of his stature capable of flipping our expectations on their back without a wink to reassure us that it’s really him. This is probably his meatiest role since Training Day and he bites down deep. From Whip’s cool amid the chaos of that cockpit to his darting glance when the word ‘toxicology’ first comes up, Washington gives us all this man’s cocksureness, his selfishness, belligerence and flashes of panic, safe in the knowledge that he has only to walk down a corridor using that patented Washington roll—as if he runs on lubricated ball bearings—and we will be with him, every step of the way.”

“Recall that Chuck Noland, the Tom Hanks character in Cast Away, survived a plane crash and faced awful solitude on a deserted island—a Robinson Crusoe with no Friday.” Time‘s Richard Corliss: “Whip, no less isolated psychologically than Chuck is spatially, has plenty of people ready to help him maintain his national-hero status and sidestep prison. In a way, the two movies are replays of classic 1950s Westerns at opposite poles: Fred Zinnemann’s Oscar-winning High Noon, where Sheriff Gary Cooper confronts the bad guys alone after the townspeople have deserted him, and Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo, where Sheriff John Wayne accumulates more ragtag deputies than he wants or needs…. Zemeckis has occasionally been criticized (by me, for example) for making films that are less than the sum of their technically innovative parts. This time, he has acutely fused two movie cultures, mainstream and indie, in a sensibility riskier than the studio norm and more muscular than the Sundance films.”

Christopher Bourne for Twitch: “Flight, despite the interesting ethical quandary it explores, reveals itself in its final moments to be conventional Hollywood melodrama to its very core, wrapping everything up in a neat bow of mass audience-pandering sentimentality.”

Updates, 10/21: “Though it’s hampered by some formulaic touches,” writes R. Kurt Osenlund in Slant, “Flight is one unique, audacious studio movie, kicking off as a star-driven spectacle before whittling itself down to a raw and riveting character study.”

“In Hollywood, is AA the new Scientology?” asks Ryan Brown at Ioncinema, where he calls Flight “an obvious, unentertaining propaganda piece.”

In the Los Angeles Times, John Horn outlines the story of the making of the film, first conceived by Gatins in 1999.

Update, 10/24: “The serious intimacy of the piece makes it surprisingly harrowing for a big-budget studio picture,” writes Jesse Hassenger for the L, “but the screenplay by John Gatins doesn’t peel back layers of revelations about Whitaker; it pretty much sets his problems on the table in the first section, which leaves only their depth to be revealed, often through repetition.”

Update, 10/26: Dave Kehr talks with Zemeckis for the New York Times: “It is difficult to imagine the mo-cap-dominated 3D blockbusters of the last several years—films like James Cameron’s Avatar or Joss Whedon’s Avengers—without the innovations that Mr. Zemeckis and his collaborators nursed along through [The Polar Express (2004), Beowulf (2007), and A Christmas Carol (2009)]. ‘With Flight,’ [Todd] McCarthy wrote [in THR], ‘Robert Zemeckis parachutes back to where he belongs, in big-time, big-star, live-action filmmaking.’ Mr. Zemeckis, though, sees no break with his standard practice, which is to use state-of-the-art technology in the service of classic cinematic storytelling. ‘It’s the same,’ he said… Short of 3D, the movie makes use of the full spectrum of digital techniques that have emerged in the last decade, from three-dimensional, digital storyboarding in the preproduction phase to the touching up of details in postproduction. The computers are still there, though this time they are churning away in the service of naturalism rather than fantasy.”

Update, 10/29: “There’s something eerily self-absorbed about Washington,” writes New York‘s David Edelstein. “He’s not an actor who opens himself up—you never quite feel you know him, underneath. But that’s why his onscreen explorations of control and its opposite feel so right, so true to who he is as a performer and a man…. This is a titanic performance.”

Update, 10/31: Keith Uhlich interviews Zemeckis for Time Out New York.

Updates, 11/1: Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir riffs a bit before turning to the film itself: “With his impressive physical presence, ladykilling charm and stern, sarcastic demeanor, Washington strikes me as a movie star from a different era, perhaps the age of Clark Gable and Laurence Olivier. That overlooks the obvious fact that a man of Washington’s background and color could never have been a major star in an earlier day, but that too—that sense of belonging both to the present and the past—is part of his appeal…. Washington might fit best projected some centuries into the future, into a universe of ‘post-racial’ entertainment that none of us will ever see. As excited as I am to see Daniel Day-Lewis play Abraham Lincoln, for example, I think Washington would be even better. And not playing Lincoln as ‘black,’ in some racially reversed alternate universe or whatever. Just playing Lincoln.”

“Denzel Washington is at home in this character,” writes the Stranger‘s Charles Mudede, “a man who saves lives but is a complete asshole. Between the plane sequence, which Robert Zemeckis masterfully directs and edits, and Washington’s Oscar-worthy performance, Flight reveals itself as one of the best films of the year.”

The Philadelphia Weekly‘s Sean Burns, who also interviews Zemeckis, disagrees: “The best movies featuring addiction—Oslo, August 31st and The Master are excellent recent examples—are about the characters, not The Problem. Flight is about The Problem.”

“In the end, Flight hinges on the question of how long Whip can keep lying and what the consequences, both material and spiritual, of that lying could be,” writes Glenn Kenny at MSN Movies. “The script by John Gatins is sufficiently well-crafted that it’s only in retrospect that one realizes that the two characters who are Whip’s friends, a sybaritic drug dealer played by John Goodman and a straight-arrow fellow pilot played by Bruce Greenwood, are pretty schematic in their devil-angel functions.”

“Of many small, telling bits in John Gatins’s screenplay,” writes Ray Pride at Newcity Film, “is a spare, breathtaking instant in the midst of the nose-down trajectory, in the form of Washington’s matter-of-fact, clipped delivery of the words, ‘black box,’ to indicate to a coworker to say a thing, to leave a certain, particular message: Whip is wholly in control in a breath. It holds the whole film in a professional gesture, from Whip, from Denzel, it’s less than a second, it’s perfect, it’s what American movies do at their best, instant after instant.”

“In one of his best performances,” writes the AV Club‘s Keith Phipps, “Washington builds the character through his actions, and sometimes just his expressions: a confident gaze here, a melting of that confidence elsewhere, and an ever-persistent hunger resting just below the surface. He plays the sort of morally conflicted protagonist sadly seen more often on cable dramas than in mainstream films.”

“As long as this amazing actor and his tormented character are flying by the seat of their pants, not giving a damn whether we like them or not, Flight soars,” writes Jason Shawan in the Nashville Scene.

“Kelly Reilly lifts the film in her scenes as a heroin addict who crosses paths with Washington in the hospital,” finds Sam Adams in the Philadelphia City Paper, “but the film’s star is so stoic it’s hard to connect with the pain that’s meant to be buried under his booze-soaked surface. Zemeckis too focuses on surfaces—the crash sequence is a stunning setpiece—but never discovers what lies beneath them.”

Updates, 11/3: “Mr. Zemeckis is in very fine form in Flight,” writes Manohla Dargis in the NYT, “and when he sends a camera whooshing down the aisle of the failing plane, the controlled movement both conveys the contained frenzy of the scene and visually echoes the chill racing along your spine. Here he achieves more than virtuosic display. By something more, I don’t mean the movie’s subject, which is, at its broadest, a tail-spinning alcoholic. Superficially, Flight is the sort of award-season entry that earns plaudits simply because its subjects are sanctified as important, serious. There’s seriousness in Flight, but not self-seriousness. And what distinguishes it is the balance of its parts and how its floating, racing cameras complement the nimble performances, rocking emotions and ups and downs of the story and music alike.”

“Not often does a movie character make such a harrowing personal journey that keeps us in deep sympathy all of the way,” writes Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times.

“Not since He Got Game has [Washington] played such a richly comprised character,” writes Tim Grierson in Screen. His “inherent decency sells this horribly flawed character to the audience—we root for Whitaker to avoid incarceration, while at the same recognizing how deluded and pathetic this man is, no matter his heroism.”

Blogging for Artinfo, J. Hoberman notes that “the strain of religious mysticism that has long characterized the Zemeckis oeuvre… is fully present. In the end, it turns out that Washington’s lawyer and his co-pilot are both right. The flight of terror really was an act of God.”

“But consider this,” writes Josef Braun: “when Whip’s willpower fails, he’s sober; when, during a hearing regarding the crash, Whip finally does the ostensibly right thing, he’s drunk! And I mean, super-stinko-drunk. And high on coke. And consider this: that ‘right thing’ that Whip does helps no one, distracts the public and industry alike from the very serious mechanical failures responsible for the crash, and essentially ruins Whip’s life. It’s a peculiar confusion of purposes: Whip’s an Icarus figure, to be punished for (literally) flying too high, yet he’s granted what is, in politically correct, 12-step program terms, a Hollywood ending. However you try to make sense of it, it’ll make you seriously consider taking the train.”

Moving Image Source has reposted Matt Zoller Seitz‘s 2012 essay on the Back to the Future trilogy, which “heralded Zemeckis’s metamorphosis from a filmmaker into an issue.”

More interviews with Zemeckis: Erik Childress (eFilmCritic) and Scott Tobias (AV Club). And Jen Yamato talks with Melissa Leo for Movieline.

Updates, 11/5: “[O]nce a scintillatingly witty young cynic (as the director/co-writer of Used Cars and the co-writer of Spielberg’s undervalued 1941), [Zemeckis has] become a specialist in vaguely New Age inspirational uplift,” writes Phil Nugent. “It’s a line of bullshit that’s most interesting for its relationship to actual inspirational uplift, which is what religion is for.”

“As the film goes along, steadily, slowly, it puts us in the ambivalent position of admiring Denzel Washington’s bravery and candor and disliking the character he plays,” writes the New Yorker‘s David Denby. “We get tired of watching Whip fail, and we’re caught between dismayed pity and a longing to see him punished. Only a great actor could have pulled off this balancing act.”

Charlie Schmidlin talks with Zemeckis for the Playlist.

Updates, 11/7: “[P]erhaps the truest indication of acting excellence comes when an actor takes a part in a mostly mediocre film overwhelmed by hackneyed supporting roles, song cues and plot devices, and creates a character more honest and compelling than almost everything else around him,” writes Jason Bellamy. “By that measure, Denzel Washington’s performance in Robert Zemeckis’s Flight is one of the best of the year.”

Flight “draws on [Zemeckis’s] formidable technical abilities to explore states of vulnerability, longing and human frailties,” writes Patrick Z. McGavin. “Just as important, it has an intuitive grasp for behavior and action that I was beginning to think eluded him.”

Film Comment editor Gavin Smith: “Integrity. That’s the quality that Washington has most come to embody in his acting across 30-plus years. It lies at the heart of his appeal, and on screen, circumstances permitting, he seems to naturally exude it.”

Listening. Slate‘s Stephen Metcalf, John Swansburg, and Julia Turner discuss Flight.

Update, 11/13: For Jim Emerson, Flight “proved to be a different, and more interesting, [film] than the movie I’d seen advertised in the trailer.” Spoilers follow.

Update, 11/14: “Flight is never less than watchable, even when it’s slack and perfunctory,” finds Dennis Cozzalio. “The problem is, as engrossing as it is, Flight never strays from the plan, and it never takes the viewer anywhere that isn’t telegraphed a mile away.”

Update, 11/18: “The brilliance of Denzel is that his incredibly resonate image is posturing as the complete lack of one,” writes Anne Helen Petersen. “He’s the anti-celebrity, the devoted actor, a model of masculinity. A star who says he doesn’t know how to be a celebrity.”

Update, 11/19: Airline pilot Patrick Smith at the Daily Beast: “I’m not sure who gets the bigger screw job here: viewers, who are being lied to, but who may or may not care; airline pilots, whose profession is unrealistically portrayed; or nervous flyers, whose fears this movie will only compound.”

NYFF 2012: a guide to the coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.