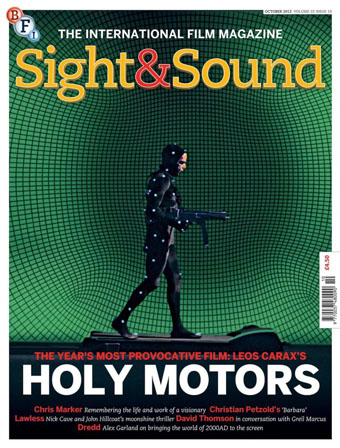

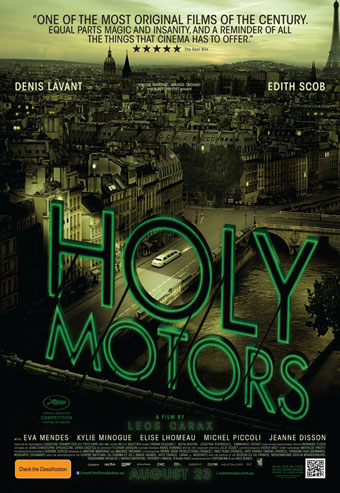

Since its premiere in Cannes, where the word “bonkers” was more than once or twice applied to Leos Carax’s first feature in 13 years, usually with affection, Holy Motors has been knocking around Europe and will hit the New York Film Festival on October 11. Today, it opens in the U.K.—where they’re loving it. Sight & Sound has put the film on its cover and the Guardian, which is streaming Holy Motors for £10 per view, has rolled out quite the package. For starters, you can watch (for free) an onstage Q&A with Carax and one of his stars, Kylie Minogue, hosted by Peter Bradshaw. That 9’36” comes with supplementary reading: Xan Brooks‘s fine profiles of both Carax and Minogue.

But on to Bradshaw‘s 5-out-of-5-star review: “There is something very mad about this film, consumed with a ferociously eccentric need to let no windmill go untilted-at. When so many filmmakers are content with what Peter Greenaway identified as pre-cinematic products—films that look like staid adaptations of novels or plays, whether they are or not—Carax really wants to use the freedom and evolved fluidity of the cinema…. Carax gives us cinephile allusions to Jean Cocteau, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Demy and Georges Franju in the course of the film; with a chilling mask, [Edith] Scob reprises her own famous persona from Franju’s 1960 film Eyes Without a Face. But more potent influences are perhaps JG Ballard, Lewis Carroll, Fritz Lang or David Lynch, whose Eraserhead and Inland Empire hover over the weird introduction, in which the director himself awakens and wanders through a darkened cinema auditorium accompanied by the unsettling sound of seagulls…. Holy Motors could be a multiple-personality disorder of the spirit, a tragicomic shattering of the self, caused by some catastrophe that has happened just out of sight, just beyond the reach of memory. But it’s quite possible it’s just bravura, imagination, fun. This is the theory I favor. It’s pure pleasure.”

Another 5-out-of-5 from Nigel Andrews in the Financial Times: “Carax made the tenebrously romantic Pola X and the love-and-death-obsessed Les Amants du Pont Neuf. He is unafraid of life’s morbid structures and humanity’s disturbing foibles and functions. Among the identities donned and doffed by the hero of Holy Motors (Denis Lavant, Carax’s favorite lead), a millionaire and serial disguise artist chauffeured through Paris one day/night in a white stretch limousine, are a dying old man, a pair of twin assassins, a movie motion-capture mime artist writhing in erotic pas de deux with a female partner, and a lecherous, scatological demon of the sewers called Monsieur Merde. If there are seven basic stories in the world, this is the one about the mutant in us all.”

“There will be no wilder, weirder movie out this year,” writes the Telegraph‘s Tim Robey, and here comes that word again: Holy Motors is “an often jaw-droppingly bonkers dive into the id.” He reminds us that Carax’s segment in the 2008 portmanteau film Tokyo! featured “Denis Lavant as a green-clad, plant-chomping hobgoblin emerging from the sewer. Once seen, never forgotten, this character returns here as just one of the 11 roles Lavant takes on in a staggering feat of actorly athleticism. Alec Guinness’s octathlon in Kind Hearts and Coronets may just have been trumped. And how.”

For Guy Lodge, writing for Time Out London, “even at its most absurd (chimps are involved), there’s something tender and truthful about Carax’s hall-of-mirrors irrationality, the sense of an artist so weary of human realities that he has no choice but to twist them into the more beautiful shapes afforded by cinema.”

“Carax, dreamer, cinephile, over-reaching fabulist, chain-smoking torchbearer for the artistic ideals of the Nouvelle Vague of the ’60s and the cinéma du look of the ’80s, has finally made a film that’s worthy of his esteemed reputation,” writes David Jenkins at Little White Lies, and at the Arts Desk, Emma Simmonds writes: “At its most broad, the film explores the nature of performance: who an actor really is behind his or her many roles, both highlighting the inherent weirdness of performers (there’s a killer punchline when we meet the real Oscar) and also the alienation and loss of oneself. A late-in-the-game appearance from Ms. Minogue shows us the sombre side of the songstress, in perhaps her most convincing big-screen outing to date (and yes, she does sing).”

Reviews are coming in from New Yorkers as well. “What Carax is articulating throughout is the visceral satisfaction of a handsomely framed image, the heartache of a whispered song of regret, the joy of a cleverly presented red herring, and so on, ad infinitum, amen.” Slant‘s Ed Gonzalez: “But Holy Motors is also more.” It “references our history of cinema, much of it the chapter on French film, sometimes Carax’s own work and sometimes even its own self, to convey the sponge-like quality of movies, their malleability, their capacity for reinvention, to celebrate not only the joy the cinema gives us, but the joy actors give each other when performing. But for all its pleasures, Holy Motors is, to quote Jonathan Rosenbaum on Buñuel‘s The Milky Way, ‘dangerously close to being all notations and no text’—a maddening, self-satisfied, though never smug, game of spot-the-reference that seems intended only for a particular type of cinephile.”

Oscar’s “whole life is performance, and performance is life, acting for an invisible crowd that we see in the opening scene lolling contentedly in their seats,” writes R. Emmet Sweeney at Movie Morlocks. “This is no celebration, though, for Oscar is exhausted, as Michel Piccoli notes in a crucial cameo. These forms and characters that Lavant so imaginatively embodies are losing their force—these grand emotions are as outdated as the lugubrious limo that creeps through town. Oscar’s tour is a joyous kind of eulogy, a superb rendering of these spectacles that is also their last.” And Glenn Kenny is actually “pleased and relieved to find Holy Motors a largely downbeat, even mordant film.”

Steve Erickson, though, writing in Gay City News, finds it to be “a perpetual motion machine,” one “that expresses a hope for cinema’s future filtered through a middle-aged maturity and concern with mortality.” David Fear in Time Out New York: “It’s a love letter to the seventh art and exhibit A for making the case that enfants terribles don’t get older—they just get weirder.”

Updates, 9/30: The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody: “In an interview decades ago, Carax said that the greatest privilege of being a director is working with actors (and he has elicited some indelible moments of performance from them). Holy Motors is as much an unpeeling of Carax’s own phantasmagorical inner screens as it is a supreme tribute to the artists who haunt them. It’s one of the great movies about acting—and about imagination as such.”

Ginette Vincendeau for Sight & Sound: “In the best auteur cinema tradition, Carax scorns the notion of narrative yet claims a grandiose project (‘Is the film telling a story? No, it is narrating a life. The story of a life? No, the experience of being alive’) and denies authorial intentionality while reinforcing it: ‘There’s never any initial idea or intention behind a film, but rather a couple of images and feelings that I splice together.’… To the old man in the car (Piccoli) who asks, ‘Why do you carry on being Oscar?’ he replies, ‘For the beauty of the gesture.’ It’s a phrase that goes for the whole film.”

The Observer‘s Philip French: “As the cinematic and literary references (to everyone from Cocteau via Buñuel to Godard) are scattered around town like confetti at a wedding or ticker tape at a hero’s motorcade, Lavant/Oscar becomes (among other incarnations) an old crone begging beside the Seine; a menacing avenger from a Feuillade silent serial; a crazed, barefoot troublemaker in an ill-fitting green suit kidnapping an American model during a photo shoot and carrying her away as if he were Quasimodo or the Phantom of the Opera; a hitman hired to kill his doppelgänger; a father concerned for his daughter’s safety; and the cheerful leader of an accordion band performing in a candlelit church. He’s Lon Chaney, the movie’s man of a thousand faces, and Sherlock Holmes, the master of disguise.”

“It was very disconcerting to see [Carax] all broken up and bitter at a Q&A session for an omnibus film, Tokyo!, in which his contribution Merde was definitely the highlight of the three,” writes Dustin Chang for Twitch. “Holy Motors is a product of a frustrated artist finding ways to express himself under difficult financial circumstances.”

And it’s topped Criticwire‘s Fantastic Fest poll.

Update, 10/7: “It is strange to think that—with this sudden return and with many of his contemporaries working in a kind of pervasive, globalized Hollywood—the once-derided Carax is probably the only filmmaker of his generation who still matters,” writes Leo Goldsmith in the Brooklyn Rail. “Holy Motors is in many ways his most bizarre work, at times his most deliberately surreal. On the surface, with its appearances by Eva Mendes and Kylie Minogue, singing a tune co-written by the Divine Comedy’s Neil Hannon, it seems almost haphazard in comparison to Mauvais sang’s playful classicism, The Lovers on the Bridge’s Vigo-esque euphoria, or Pola X’s inexorable plunge from grandiosity to austerity. But in many ways, Carax’s new film is also curiously calculated and serene, especially in its final acts, when the extremities of its earlier scenes give way to a profound melancholy, a set of earnest rituals that reenact the scenes of death and regret. If the cinéma du look was always an emphatically Mitterand-era cinema, a well-funded commodity for a grown-up, calmed-down, and upper-middle-class Left, it is high time for Carax to return to answer this with a film, at once angry, absurdist, and elegiac, that heralds the arrival of a post-Sarkozy era.”

Update, 10/10: Kenji Fujishima at the House Next Door: “Carax is hardly the first to bemoan a perceived lack of ‘authenticity’ in increasingly ubiquitous digital cinema, waxing nostalgically about the good ol’ days of analogue filmmaking; film critics/cinephiles have been lodging these kinds of complaints for years now—and still are, if the recent rash of ‘death of film/film criticism’ literature is any indication. Holy Motors takes this nostalgic attitude as received wisdom, and it has the effect of adding an ironic veneer to even the most emotionally affecting of individual sequences that some might find off-putting, if not outright nihilistic. But no film as full of creative energy and imagination as this one can be said to be entirely nihilistic. A more valuable way to look at Holy Motors, then, is on the more intimate level of a character study: a Brechtian contemplation of an actor who gives so much of himself in his performances that, for him, real life and acting merge until they become inextricable.”

Updates, 10/12: “This is a filmmaker who knows from lost time,” writes Dennis Lim in a profile for the New York Times. “‘I’ve done 10, maybe 12, hours of film in 30 years,’ Mr. Carax said one recent afternoon, in an interview at a tea shop in his Belleville neighborhood here. He did not sugarcoat his conclusion: ‘I’m not a cineaste. I’ve made so few films. Sometimes it feels each one is the last one or the first one.'”

Tom Hall argues that Holy Motors is “the first film of the 21st century to tear apart the modern conditions of filmmaking and expose their ultimate superficiality. I think the film is a masterpiece and will stand as a vital document that describes the challenges and problems facing filmmakers who confront an industry that continues to spiral away from authentic human experience toward a completely artificial, isolated world driven by money, surface and condescension. Not only is this painful realization at the heart of Carax’s film, it is literally its narrative subject; written by Carax in a ‘rage for being unable to get a film made,’ Holy Motors is an incendiary, often hilarious, manifesto in favor of putting human feeling back into the movies.”

Chris Wisniewski in Reverse Shot: “This is a movie about movies—and one might say, about film specifically—but also about death, obsolescence, performance, movement, technology, machinery, and spectatorship. Carax draws these themes together both explicitly and obliquely and largely trusts that his audience will understand their interrelatedness—specifically how the cinema itself seems to subsume and expand outward to touch on each of these ideas, even if this particular film refuses to (and could never possibly hope to) overtly connect the dots.”

Updates, 10/13: Blogging for the Voice, Nick Schager notes that, as Merde, the character introduced in Carax’s Tokyo! short, Lavant “enacts a wacko Beauty and the Beast-style affair with Eva Mendes’s unperturbed fashion model in a sequence of supreme hilarious craziness that features Mendes’s dress being cut into a burka and veil, and a nude and fully erect Levant lying his head in Mendes’s lap while she sings him a lullaby. The point of this episodic insanity, as it were, would seem to be simultaneously expanding and collapsing the possibilities of film, all while recognizing life (like cinema) as a myriad series of roles to be assumed and jettisoned—including, according to Carax’s loony finale, marriage and parentage to monkeys.”

Hillary Weston talks with Carax for BlackBook.

Update, 10/16: For Artinfo, J. Hoberman writes that Lavant’s “professional life-actor (if that’s what he is) keeps entering different scenarios—a frumpy hipster picking up his teenaged daughter from party, a musician leading a band of accordionists through a cathedral, and, in the movie’s most alienating sequence, an assassin bloodily dispatching his double. It is at this point that the movie wounds itself, devolving from pure irrationality into a sort of sub Jacques Rivette theatrical conceit involving a cosmology that might have been imagined by Charlie Kaufman.”

NYFF 2012: a guide to the coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.