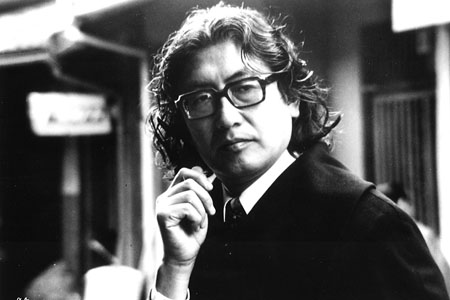

The German Press Agency is confirming widely tweeted reports of the passing of Nagisa Oshima at the age of 80. “For many critics and cinephiles who came of age in the 1960s and ’70s,” wrote Dennis Lim in the New York Times in 2008, Oshima “has long held the mantle of Japan’s greatest living filmmaker.” The occasion of the piece was In the Realm of Oshima, a retrospective curated over a period of ten years by James Quandt of the Cinematheque Ontario. The retrospective travelled throughout North America that year as “a bid to safeguard a master’s place in the canon.” Going by the sheer bulk of critical appreciation it generated a little over four years ago, it was a resounding success.

Dennis Lim: “If Mr. Oshima’s legacy now seems a bit murky, it is partly because he was, by design, a tough filmmaker to pin down. Several thematic threads run through his movies—sex, crime, an alertness to the social and political dimensions of his characters’ transgressions—but there is no stylistic signature. Mr. Oshima swerved between extremes, reshaping familiar genres (family epics, youth films) and inventing new ones (freely mixing modes like documentary realism and avant-garde surrealism), always searching for radical forms to match radical content.”

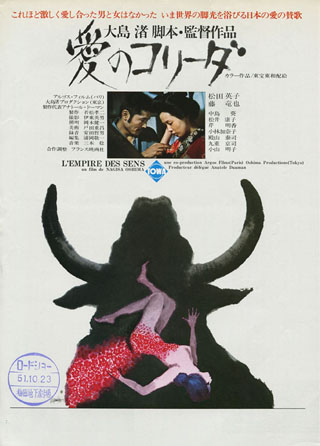

Two years later, Dave Kehr would note in the NYT that “Oshima achieved worldwide fame with the 1976 release of his sexually explicit art-house hit In the Realm of the Senses. Based on a true incident from the 1930s, it tells the story of a couple who withdrew from the increasingly authoritarian culture of imperial Japan into a private world of nearly constant sexual stimulation. The idyll comes to an end when the male partner dies during an act of erotic asphyxiation, and the woman, refusing to relinquish her happiness, cuts off his penis as a keepsake. Most of Mr. Oshima’s themes are present in this plot: his rejection of traditional Japanese hierarchical culture, his fascination with instinctive rebels, his suggestion that sex is at once the rebel’s most powerful weapon and most fatal distraction. But for all of its transgressive force, In the Realm of the Senses remains one of Mr. Oshima’s most stylistically conservative films, telling its story in a linear, naturalistic way with bright, balanced, classically composed images.”

The occasion of Kehr’s 2010 piece was Criterion’s release of Eclipse Series 21: Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties, collecting five films made between 1965 and 1968, “smack in the middle of Oshima’s most productive period, and a dizzying phase even by the standards of this master iconoclast who famously defies classification and rarely repeated himself,” as Dennis Lim (yes, again), wrote in the Los Angeles Times (the review is no longer available online). And Dave Kehr noted that these were the “years between the commercial triumph of his early, teen-cult films (like Cruel Story of Youth and The Sun’s Burial, both released in 1960) and his rediscovery by Western critics at the end of the decade, when politically provocative works like Diary of a Shinjuku Thief [1969] and The Man Who Left His Will on Film [1970] made him seem an Asian cousin to European iconoclasts like Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Marie Straub.”

Catherine Grant has already begun to gather links to tributes and online studies of Oshima’s work, and four of them take us to Moving Image Source, edited, of course, by Dennis Lim. We’re back in 2008, and the retrospective is rolling across the continent. Chris Fujiwara: “From the beginning of The Man Who Left His Will on Film, Oshima draws us into an urgent movement. Someone—’we,’ let’s say, since we see the scene through a ‘subjective’ camera lens—has taken a movie camera that belongs to a revolutionary film group, which seeks to reclaim it. This struggle over a camera, and, through it, over a means of seeing and a structure of seeing, is crucial to the film. Who owns images? The collective affirms that if certain values are not evident in the image, the image is worthless. The individual, on the other hand, is the site of ambivalence: a film may invoke collective values, or not; just as important is the presence or absence of a sensibility, of a stream of experience, of a recognition.”

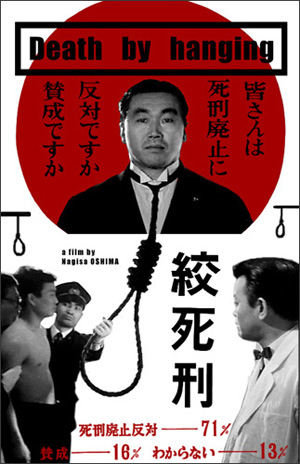

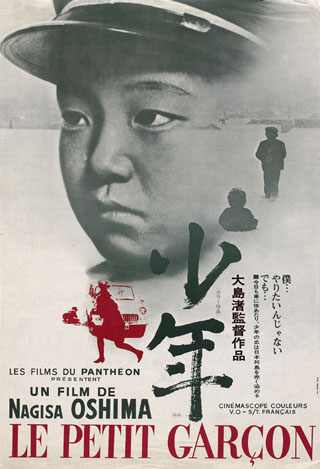

“Going so far as to challenge the very concept of ‘character’ in cinema by leaving its nominal protagonist’s very identity an open question, Death by Hanging [1968] is among Oshima’s most radical narrative experiments,” writes Joshua Land. “Superficially tamer but ultimately even more corrosive, Boy (1969) unfolds in a fairly straight narrative line. By the standards of Oshima’s rogues’ gallery, the family at the center of the film is almost benign; their game is running out in front of cars and extorting settlement money from the drivers. Boy thus returns to the blackmail motif of Cruel Story of Youth but Oshima’s view of criminality has clearly evolved: in the earlier film, the young blackmailers were both products of respectable society and outcasts from it. Here, criminality is not a product of society; it is society.”

Michael Atkinson on In the Realm of the Senses: “It might just be the most lucid and uncompromised film about gender politics ever made by a major Asian director. Given that Oshima was hurtling down the tracks laid by Mizoguchi and Ozu, and by the courtesan tragedies of the Edo period, that’s saying a great deal.”

“And then there’s 100 Years of Japanese Cinema [1995],” writes Rob Nelson, “Oshima’s Histoire(s) du cinéma at one-fourth the length. ‘My hatred for Japanese cinema includes absolutely all of it,’ the director famously told an admirer of Mizoguchi and Kurosawa. Who better, then, to subvert the very notion of a You Must Remember This doc—of a Japanese Cinema if not Japanese cinema? The BFI’s bold commissioning of Oshima to make this portion of its 1994 Century of Cinema series—allowing final cut, presumably—stands among the greatest tributes to the director within what will likely remain his final decade of work. And the film, precisely for its irreverence, earns that honor in full.”

Also in 2008, David Phelps wrote a four-part series on Oshima for the Notebook. In the first, he took note of a “favorite patterning of Oshima’s… probably derived from a Japanese film he did like, Rashomon: similarly, Death by Hanging will constantly propose alternate perspective and styles to recreate recreations of a forgotten event, Sing a Song of Sex [1967] will split into competing fantasies, each as plausible as another, and Three Resurrected Drunkards [1968] simply restarts halfway through with the same opening scene intact, to indicate, Clue-like, an alternate direction the same root might spring. Oshima’s usual penchant runs through it all: break-down ontology altogether. There is no single way things could happen, and there certainly is no single way we can really know what happened: that’s simply a matter of perspective (the style famously changes every Oshima film), and usually it’s the perspective of delusive liars and dreamers and cheats whose unwilled hallucinations and self-told fantasies, enacted on-screen, are as true and false as anything up there.” And the series continues: Parts 2, 3, and 4. And he wrote more Oshima here, while Daniel Kasman reviewed Dear Summer Sister (1972): “This film from 1972 strips the director’s duly noted and deservedly praised formal compositions resembling a cross between Antonioni’s architectonic modernism and a comic book’s brash stylization for—believe it or not—a typically early 70s, handheld, verité layabout ease.” Danny, too, wrote more: here.

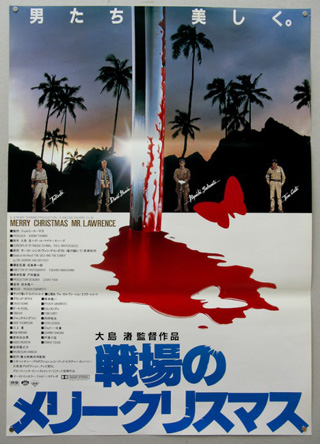

Then, of course, there’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), which “fascinates mostly for the hit-and-miss alchemy of its discordant elements,” writes Bill Weber in Slant: “in performance, pop-star charisma versus British actorliness; in narrative style, genre expectations coming up against modernist psychosexual undercurrents. The first film by Japan’s great auteur Nagisa Oshima to feature mostly English dialogue, and his most widely seen in the West thanks to a co-starring role for David Bowie, its framing and editing is more superficially ‘conventional’ than Oshima’s ’60s and ’70s masterworks, but its themes of crippling nationalism, thwarted passion, and societal derangement are of a piece with them.”

The “central joke” of Max, Mon Amour (1986) “is not so much that a bored woman would have an affair with a chimp,” wrote Fernando F. Croce in Slant, “but that, for the sake of the couple’s stability, the jabbering monkey is ludicrously integrated into the genteel family.” And 1999 saw the release of Oshima’s first feature after Max, Taboo, which, in the Voice, J. Hoberman called “an action film at once baroque and austere, hypnotic and opaque—a samurai drama punctuated by thwacking kendo matches in which the romantic swordsmen keep falling in love… with each other.”

Updates: In the Guardian, Ronald Bergan takes us back to the beginning: “Born in Kyoto, Oshima studied political history at Kyoto University, where he was a student leader involved in leftwing activities, prior to graduating in 1954. He then became a film critic and later editor-in-chief of the film magazine Eiga Hihyo, before learning his craft as an assistant director at the Shochiku Studios. Oshima started directing his first features at the time of the French New Wave, whose influence he came under, especially that of Jean-Luc Godard…. The neorealist Night and Fog in Japan (1960)—the title deliberately designed to echo Alain Resnais’s documentary on Auschwitz—was a despairing indictment of the disunity of the Japanese left, and what Oshima saw as the betrayal of revolutionary action by the Japanese Communist party. The film, which contains only 43 shots, was withdrawn by the studio three days after its release, which pushed him to working as an independent and to found his own production company, Sozosha, with the actor Akiko Koyama, whom he married in 1960.”

Here’s how Jonathan Rosenbaum opened a piece for Artforum in 2008: “No major figure in postwar Japanese cinema eludes classification more thoroughly than Nagisa Oshima. The director of 23 stylistically diverse feature films since his directorial debut in 1958, at the age of 26, Oshima is, arguably, the best-known but least understood proponent of the Japanese New Wave that came to international prominence in the 1960s and ’70s (though it is a label Oshima himself rejects and despises). Given the size of his oeuvre and the portions that remain virtually unknown in the West—including roughly a quarter of his features and most of his twenty-odd documentaries for television—the temptation to generalize about his work must be firmly resisted.”

When In the Realm of Oshima arrived in Berkeley, Michael Guillén spoke with James Quandt. For quite a while, too, covering the retrospective in considerable depth: Parts 1 and 2. Michael‘s linking to some of his own pieces on Oshima as well.

“Oshima was a brilliant satirist, provocateur and poet of the senses whose movies were elegant, angular weapons against stifling hypocrisy and confirmity,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw.

“Oshima’s films have meant a lot to me ever since I was haunted for days by The Man Who Left His Will on Film, nearly ten years ago,” writes Brian Clark at Twitch. “As I’ve worked through his filmography in the ensuing years, his films have continually astounded me, perplexed me and challenged the way I thought about cinema. I still don’t believe there is any other filmmaker who has managed to make films that are so direct and confrontational while simultaneously experimental, and even playful.”

With a blurb for each at the AV Club, Scott Tobias recommends “five films for the queue.”

Updates, 1/16: From Dennis Lim‘s obit for the NYT: “Mr. Oshima recalled that In the Realm of the Senses had originated in a meeting with the producer Anatole Dauman, who had worked with many French New Wave directors and who proposed a collaboration, saying to Mr. Oshima, ‘Let’s make a porno flick!’ Mr. Oshima asked his colleague Koji Wakamatsu, a prolific director of politically minded soft-core erotica, to serve as a producer as well; together they had the film processed and edited in France to circumvent Japanese pornography laws. Mr. Dauman also produced Empire of Passion, the more subdued 1978 follow-up to In the Realm of the Senses. Another period piece about adulterous lovers, Empire won Mr. Oshima the directing prize at the Cannes Film Festival…. Testifying in a Japanese court about In the Realm of the Senses, Mr. Oshima formulated a defense that could apply to almost all his work: ‘Nothing that is expressed is obscene. What is obscene is what is hidden.'”

Writing for the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Robert Koehler notes that “as his sometimes chippy contemporary and even more radical fellow filmmaker Masao Adachi has written, Oshima is possibly most helpfully viewed alongside Jean-Luc Godard, whose Vent d’Est (1969) has a conversation of sorts with a 1970 film by Oshima that now contains a premonitory title, The Man Who Left His Will on Film. Both having reached a real sense of skepticism in the dying strains of revolutionary politics, each artist took, in Adachi’s words, ‘as their duty to question the matter of film in its entirety.’ It isn’t that each man paralleled each other, any more than Oshima paralleled Wakamatsu, but the Brechtian devices each deployed as a filter on their observations and immersions in that violent and heady moment—which Wakamatsu dramatized near the end of his life as a careening group leaping into madness—allowed them a certain distance from the maelstrom that trapped fellow artists, but which each avoided by striking, different means.”

Criterion‘s posted a collection of “Words and Images.”

Updates, 1/17: At Artinfo, Graham Fuller reminds us that In the Realm of the Senses “was shot against the backdrop of rising militant imperialism and the 1936 army coup against the government that led to the assassination of three elderly leaders and triggered the resignation of Prime Minister Keisuke Okada and his cabinet. Read Donald Richie’s analysis of the film here.”

“I did find it curious to discover that Oshima interviewed Akira Kurosawa in 1993,” recalls Peter Nellhaus. “In Joan Mellen’s interview with Oshima, the younger filmmaker expressed his disdain for the man who personified Japanese cinema for many western cinephiles, making a pointed remark about Kurosawa’s most recent film at that time, Dodes’kaden. But this change of heart is not entirely surprising as age has a way of making us feel more sympathetic towards our elders. One can only wonder what films we might have had seen, had Oshima had the same kind of health, or perhaps simple tenacity, that kept Kurosawa active at a time when the younger man could only make one more film.”

Ryan Gilbey links to a piece he wrote for the New Statesman on the occasion of the retrospective’s arriving in London in 2009 and adds a quote from David Bowie: “What a tremendous eye he has. He’s so quick with his decisions… After the first couple of days, we realized it was going to be one-take stuff—one take, two takes. And that really fired us up; I think that got us through the movie more than anything else, this terrific momentum. You’d go through a scene, you’d be done, and then you’d be moving on to the next scene immediately, so you were always your character, with no chance to see the overall thing.”

Tom Sutpen at the Chiseler: “His passing isn’t about Me, the Movie Reviewer; nor … though many will not bring themselves to comprehend this (how on earth could they?) … is it about the rest of my Critical brethren. It’s only and completely about him.”

Update, 1/18: Viewing. Oshima’s interview with Kurosawa, the one Peter Nellhaus mentions, is on YouTube. For English subtitles, make sure the captions are on. Via Dana Stevens.

Update, 1/19: Slate‘s Dana Stevens on In the Realm of the Senses: “It is, I suppose, a shame that a filmmaker as multifaceted (and as fiercely political) as Oshima will be remembered primarily for his raunchy succès de scandale. But you’ll have to look elsewhere for a critic to champion the director’s obscure cuts, because In the Realm of the Senses happens to be one of my cinematic Ur-texts, a movie that would easily find its way onto my personal list of top 10 films of all time. When I heard the news that Oshima had died, it was my vivid sense memory of this film—which I’ve seen probably half a dozen times in my life, the last of them more than 15 years ago—that sent me to my editor asking if I could write something on Oshima: neither an obituary nor a review, but a history of my now decades-old love for his most famous film. And then my editor said yes, and I almost wished I hadn’t asked.”

Updates, 1/26: “It was probably inevitable that when these middle-period films reached the west Oshima would be seen as somehow a ‘Japanese Godard,'” writes Geoffrey Nowell-Smith at Film Studies for Free. “But the comparison is misleading. It is true Oshima stood out among his Japanese peers rather as Godard did among the French. Also, like Godard, he made films fast and according to his own recipe, and these films fitted into a climate of a political militancy that was as intense in Japan as anywhere in the West, if not more so. But the similarities do not go far and Oshima himself was eager to avoid any invidious comparisons. Asked at the time what he and Godard had in common, he replied: ‘Two things: cinema and politics.’ The remark should be taken literally, as meaning simply, we both make films and we are both on the left politically. Beyond that, the differences are more significant than the similarities.”

J. Hoberman at Artinfo on Band of Ninja (1967): “Unable to fund a live-action version of Sanpei Shirato’s epic manga, published in 17 volumes between 1959 and 1962 during the very period of the polarizing Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, Oshima photographed Shirato’s crude kinetic panels (energetic drawings, many softened by a smudgy wash reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s early Dick Tracy paintings). He then added character voiceovers, as well as an intermittent benshi-style narrator and cartoon sound effects, to create a symphony of non-stop static action. The montage results in long passages of near-abstract mayhem while movement is largely confined to the occasional passing of a long scroll before the camera…. [T]he ‘historical materialism’ that infused Shirato’s manga and endeared it to the radical students of the ’60s is a constant. Band of Ninja manages to cram a half dozen battles into its final two minutes to end with the New Left exhortation that ‘The People Will Keep Fighting!’ It’s a true tour de force: Lines on paper have seldom seemed so violent.”

Noting that Oshima “frequently on television variety shows, unashamedly displaying his acerbic take on Japanese culture,” Roger Pulvers writes in the Japan Times: “Some criticized him for becoming a popular figure, claiming that this diminished his artistic legacy. But Oshima immensely enjoyed these forays into the world of the commercial hoi polloi…. Throughout a more than 30-year-long friendship with him, I frequently witnessed his wicked and pointed sense of humor, directed right at the heart of the Japanese.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.