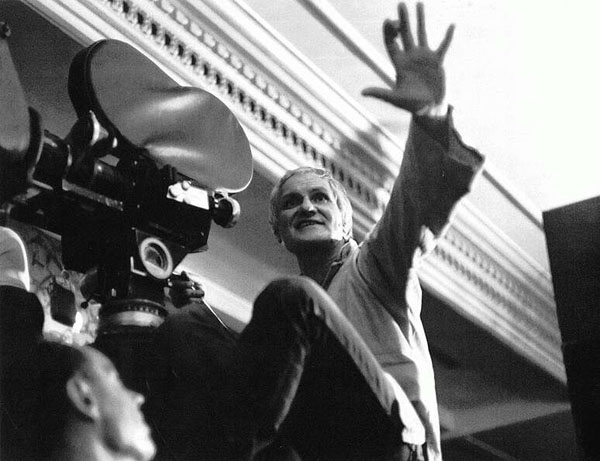

“Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó, winner of the best director award at the 1972 Cannes film festival, has died,” reports the AP. “Known for his long shots and for depicting the passage of time in his historical epics merely by changes of costume, Jancso won his Cannes award for Red Psalm, about an 19th century peasant revolt.”

About a decade ago now, Kinoeye editor Andrew Horton introduced a special issue, “Images of power and the power of images: The films of Miklós Jancsó,” by noting that Jancsó, “suffers an unusual fate in film history. His name is frequently mentioned in film history books, he is a recognized giant of Hungarian, European and world cinema and his unique visual style and complex studies of power and the relationship between history and the individual have been feted. The trouble is that, despite the above, outside his native Hungary surprisingly few people have seen—or can even tell you the name of—any of his films. Among those who have experienced Jancsó’s work, his reputation chiefly rests on a very small body of films made within six years of each other—Szegénylegények (The Round-up, 1965), Csillagosok, katonák (The Red and the White, 1967) and Még kér a nép (Red Psalm, 1971)—despite the fact that his career in film stretches across more than five decades and covers over 25 features and innumerable documentaries. Even in Hungary large portions of his oeuvre have been ignored (although this is starting to change).”

Alberta’s Metro Cinema introduced a retrospective in 2009: “Drawing on incidents from Hungary’s turbulent recent past and dramatized around the theme of power as a destructive force in human society, a Jancsó film is visually distinctive with its long shots, virtuoso CinemaScope pans, and striking black and white images. Jancsó stages his existential dramas in a horizontal landscape dotted with rough-hewn barns and silver birch forest, and peopled by warring horsemen, brutalized peasants, and handsome women stripped of their pride by arrogant men in uniform.”

Kevin B. Lee‘s 2012 video essay “Mapping the Long Take: Béla Tarr and Miklós Jancsó”

“Jancsó has never ceased to make intensely political films, which may be one reason he is so little known outside his native Hungary,” wrote Gordon Thomas in Bright Lights Film Journal, also a good number of years ago. “More simply, the biggest reason may be that his films are ‘difficult,’ even as art-house fare back in its ’60s heyday. Jancsó’s historical films, like The Red and the White, are punishingly bleak in tone and outcome. Such a tone was all well and good for cineastes of the ’60s and ’70s, but the director’s oblique way with his narratives challenged even the most dedicated among them…. Commentators often note that Jancsó refrains from psychologizing his characters—that is, why does this or that individual behave in this or that manner—but it seems he’s quite astute in portraying the numbing, reductive effect of torture in the form of base humiliation or just plain mind-fuck.”

The 2009 retro eventually traveled to Vancouver and to Berkeley, where Jason Sanders wrote that Jancsó’s “narratives tell of revolution, massacre, and betrayal, metaphors for contemporary oppression; but their visuals, ever flowing, never stopping, create an oppositional force of constant movement, resistance, and life.”

For more reviews of Jancsó’s work, championed in the States by New York Film Festival founders Richard Roud and Amos Vogel, see the Kinoblog.

Updates: Jancsó’s “films made full use of the art of cinema, with sensuous images captured by cameras that moved as gracefully as a ballroom dancer,” writes Noel Murray at the Dissolve. “Jancsó used politics as a backdrop but focused more on people, emphasizing their passions as much as much as their ideals.”

A clip from ‘Silence and Cry’ (1968)

“The ‘tracking shot in Kapo,’ a little seen film by Gillo Ponecorvo, has become short hand for a type of aestheticization of the Atrocities of War,” writes Peter Labuza. “Miklós Jancsó’s tracking shots don’t offer easy aesthetic answers in terms of their morality.” His “political explorations justify such aesthetics. He lived in a country that was literally torn: first during the war, and secondly between its Soviet influence and its Western aspirations. A film like The Red and the White, the agreed upon canonical title of his work, presents an seemingly unending war in which victors, villains, and victims are all one in the same. His idea of a tracking shot is not to sweep us up in emotion. It’s to throw us around into the shit.”

“At the peak of his popularity, Jancsó was a major box-office draw in his native Hungary (where 1 in 10 people saw The Round-Up in theaters) and enjoyed a reverent following abroad,” writes Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club. “The period of 1962 to 1972 is widely seen as Jancsó’s creative peak, and coincided with his second marriage to another of Hungary’s greatest filmmakers, Márta Mészáros. Though he continued to make films in Hungary, Jancsó also worked in Italy throughout the 1970s; largely overlooked, his Italian work included The Pacifist (1971)—which found Jancsó working with two Antonioni regulars, actress Monica Vitti and cinematographer Carlo Di Palma—and the bawdy, orgy-like Private Vices, Public Pleasures (1976). He returned to Hungary full-time in the late ’70s, eventually abandoning the historical backdrops that had distinguished his earlier work in favor of contemporary settings. Rarely screened abroad, the films of Jancsó’s late period saw him embracing comedy; the self-deprecating Lord’s Lantern in Budapest (1999), which featured Jancsó and Hernádi as themselves, proved to be a major success. Jancsó continued directing into his late 80s, most often in collaboration with István Márton.”

Updates, 2/1: “There are few directors so akin to a choreographer,” writes Ronald Bergan in an excellent appreciation in the Guardian. “His cinema does not conform to narrative or psychological conventions, but opens other areas that are usually found in the screen musical. His films are elaborate ballets, emblematically tracing the movements in the fight for Hungarian independence and socialism. In these ritual dances of life and death the Whites defeat the Reds, the Reds defeat the Whites. Tyranny is everywhere, and men and women, stripped of their clothes, are vulnerable and humiliated—nudes in a landscape. People survive in groups, often singing and dancing.”

Lest we forget: one of the best texts on Miklós Jancsó was among the last written by Raymond Durgnat – http://t.co/hRLnlXZKTo

— Adrian Martin (@AdrianMartin25) February 1, 2014

Updates, 2/2: “Mr. Jancso was born to a Hungarian father and a Romanian mother in Vac, north of Budapest,” writes Bruce Weber in the New York Times. “He studied law before entering film school in Budapest. In the 1950s, in Soviet-controlled Hungary, he made newsreels. He later directed documentaries before turning to feature films. For a time he was also a theater director. Mr. Jancso received lifetime achievement awards from the Cannes Film Festival in 1979, the Venice Film Festival in 1990 and the Budapest Film Festival in 1994.”

In 2010, the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody introduced the clip below—it’s from Electra, My Love (1974)—and recalled catching, in 2003, “a special screening of a new film by Jancsó, the mere fact of which came as a big surprise: no film of his, as far as I knew, had been released in New York for several decades, and so, I confess, I didn’t know that the director… was still alive, let alone still working. The film, Wake Up, Mate, Don’t You Sleep, is a historical fantasy, a masque of Hungary’s grim modern history, in which the eighty-one-year-old director himself and his longtime screenwriter, Gyula Hernádi, wander through a landscape inhabited by the country’s political ghosts, including impersonators of Hitler and Stalin, along with well-groomed and white-shirted nationalist rappers and—in one of the most subtly, poignantly philosophical scenes in the recent cinema—a trip in a cable car overlooking Budapest, in which a young girl whistles Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy.’ I emerged from the screening in a state of multiple ecstasies.”

Updates, 2/21: “His camera was as astonishingly fluid as Max Ophüls’,” writes Fernando F. Croce for Movie Mezzanine, “yet the sense of movement was always at the mercy of an atmosphere of encroaching entrapment, of inescapable persecution. In few of Jancsó’s films is that paradox more crystalline than in The Round-Up, the 1966 release that first brought international attention not only to its director, but also to Hungary’s film industry.”

“One lasting indication of Jancsó’s popularity in the 60s and 70s, at least in the U.K., are the gorgeous series of posters made by woodcut artist Peter Strausfeld for the Academy Cinema in London,” writes Adrian Curry in the Notebook. “It seems that between 1964 and 1974 nearly every Jancsó film was released at the Academy and Strausfeld documented each one.” And they are indeed amazing.

Update, 2/23: “It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that I regard Jancsó Miklós as one of the great lost continents of world cinema, especially outside Hungary—and largely, I suspect, because Hungarian history, which forms a major part of his oeuvre, is another lost continent from the vantage point of the West.” So begins Jonathan Rosenbaum‘s remembrance, read out at the February 22 memorial service.

Updates, 3/24: “The language that Jancsó forged, drawn as much from dance choreography as conventional dramaturgy, remains utterly distinctive to this day,” writes Michael Brooke for Sight & Sound. “This is partly because he has had hardly any imitators…, but mostly because it was drawn from the very particular circumstances that he enjoyed as a Hungarian filmmaker. Not only was he able to make regular use of the puszta, that great featureless plain so characteristic of his country’s topography (and which has few equivalents elsewhere in Europe, making a British or French Jancsó scarcely imaginable), but as an internationally recognised artist in a Communist country he was granted access to dozens, sometimes hundreds and occasionally even thousands of extras—and horses—with which to populate his increasingly extravagant visions. And if censorship frequently forced him into allegory and symbolism, that was often to the film’s advantage, not least in appealing to non-Hungarian audiences who might not otherwise grasp the political and cultural nuances.”

Christopher Mildren for Senses of Cinema: “While other directors working into their 80s and beyond, such as Jean-Luc Godard or the late Alain Resnais, display great eclecticism, Jancsó shares with them a collective formative moment in film history. It is his seminal works of the 1960s that enshrine his position in the canon of great modernist art cinema auteurs.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.