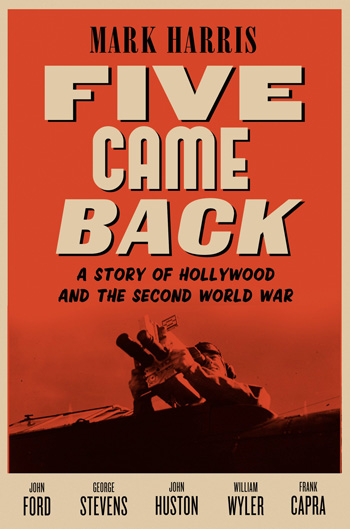

The number five seems to work pretty well for Mark Harris. His widely praised 2009 book Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood focused on the race for the Best Picture Oscar in 1968, when Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, and Doctor Doolittle presented an ad hoc group portrait of the old and new regimes going head-to-head (to-head-to-head-to-head). In his new book, Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War, Harris tells the stories of five directors who went off to “the good war” to make, not to put too fine a point on it, propaganda. Five: varied enough, but not quite a crowd. And both books happen to come in at around 500 pages.

Five Came Back is “vintage Harris, a story lying around in plain sight that everybody knew pieces of, just waiting for a gifted journalist to bring it in for a landing,” writes David Kipen at OZY. “The cast of characters approximates what Pauline Kael once called a classic ’40s-movie bomber-crew cast: the plucky Sicilian kid (Frank Capra), the sensitive Jew (William Wyler), the irascible old Irish colonel (John Ford), the spoiled playboy (John Huston) and George Stevens, a cheerful, can-do Californian who’d always succeeded at anything he put his hand to. By the time the war ended, other cliches would come true: Together and separately, some of these five would panic under fire, and some would rise to hitherto unsuspected heights of heroism. None would sustain life-threatening wounds except—whether for a year or, sadly, a career—creatively.”

The book “expansively covers the directors’ entire war experience (Wyler lost the hearing in one ear, Huston suffered PTSD) yet the sections about the fraudulent movies leap out, presenting a healthy challenge to the hagiographic Greatest Generation narrative that has shaped our sense of the war,” writes Caryn James at the Daily Beast. “And the truth resonates strongly with our own era, full of suspicions about government honesty—from the bogus reasons for invading Iraq to NSA surveillance—and our open-eyed acceptance of how fact and fiction merge even in so-called documentaries.”

To the Shores of Iwo Jima (1945), produced by the U.S. Navy and Marines; as far as I can tell, no director is credited

“Most of these men were middle-aged, with family and financial obligations,” notes M.G. Lord in the Los Angeles Times. “Yet for reasons more personal than patriotic, each renounced big bucks to bivouac among common soldiers, a decision that affected both support for the war and their own artistic lives…. Harris charts the fighting chronologically, following each director through his own circle of wartime hell. He ends with the revealing contrast between Wyler’s immediate postwar masterpiece, The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and Capra’s concurrent flop, It’s a Wonderful Life…. Where Capra sought to divert viewers with fantasy and fight ‘atheism,’ Wyler focused on returning vets, their questioning of institutions, their agonizing re-integration into civilian life…. Harris’ pairing of Wyler and Capra speaks volumes. But I wish he had also lingered on Stevens’ postwar work. For example, Giant (1956) is a potent critique of discrimination based on ethnicity. It echoes the Nazi persecution of Jews.”

For Slate‘s Aisha Harris, “Harris once again weaves remarkable, detailed stories together to reveal a more holistic view of cinematic and American history.”

As noted the other day, the New Republic‘s Isaac Chotiner has talked with Harris about recent attacks on Hollywood from the left.

Updates, 3/3: “Like the best World War II films,” writes Thomas Doherty in the New York Times, Five Came Back “highlights marquee names in a familiar plot to explore some serious issues: the human cost of military service, the hypnotic power of cinema and the tension between artistic integrity and the exigencies of war. Mr. Harris shows how—more than Technicolor, CinemaScope or even the collapse of the Production Code—World War II changed the way Americans looked at the movies.”

Listening (24’42”). Harris is a guest on the Leonard Lopate Show.

Updates, 3/30: “Five Came Back is a splendidly written narrative, but it presented Harris with a structural problem,” finds the New Yorker‘s David Denby. “Moving slowly and steadily, he uses the directors’ adventures as a way of informally telling the story of America’s participation in the war. It’s a strategy that causes him to jump back and forth among his heroes, and, at times, he leaves a director stranded at the start of a project, crew at the ready, only to pick him up thirty pages later. Writing a definitive history has its perils, and Harris tells us more than we want to know, chronicling aborted or stalled projects and endless tussles with the military over assignments and the tone and the explicitness of combat footage that the public might see. But his characterization of the directors is shrewd and engrossing, and he’s at his best when he dramatizes the men facing live fire and grappling with the film medium.”

“Harris knows all about the directors’ art as well as their lives, treats them all with fairness, and he doesn’t neglect their humor, either,” writes Farran Nehme, who “got in touch with Mark, with whom she’s friendly, and asked if he’d answer a few questions via email for the benefit of her patient readers. He kindly agreed.”

In the San Francisco Chronicle, Carrie Rickey calls Five Came Back a “can’t-put-it-down history,” and Variety‘s running an excerpt.

Update, 3/31: “Capra, an Italian immigrant whose politics Katharine Hepburn described as ‘Happy to be here,’ was enough of a naïf before the war that he could admire both Roosevelt and Mussolini, but his earnest faith in American liberty informed Prelude to War’s central dichotomy,” writes Will Sloan for Hazlitt. “To my eyes, Capra comes across as the most natural propagandist among his contemporaries. He had an instinctive understanding of how to undercut the enemy’s ideology; an ability to boil down complicated concepts and histories into bite-sized nuggets; and a fondness for sentimentality.”

Update, 5/5: “I recommend the book for its narrative sweep, its revelation of character, and for the many ironies that attend the idea of ‘documentary,'” writes David Thomson in the New Republic. He then turns to John Huston’s The Battle of San Pietro (1945). “In Time, James Agee called it ‘as good a war film as any that has been made,’ and writing in this magazine, Manny Farber recognized the daring innovation of war being ‘confused, terrifying, surprising and tragic.'” And Thomson suggests that the film “has a case for being the most powerful film made by the American documentary effort during World War II. It might be stronger still if the War Department had not cut out many of the scenes of the dead.”

Update, 6/14: Noah Isenberg for the Nation: “Although Hollywood—in particular its major studios and chief executives—has come under heat recently for its supposed lack of proper engagement during World War II, the story that Harris tells, while not always heroic, demonstrates the kind of complex moral reckoning and personal sacrifice that, until now, has rarely been recognized with such sensitivity and depth.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.