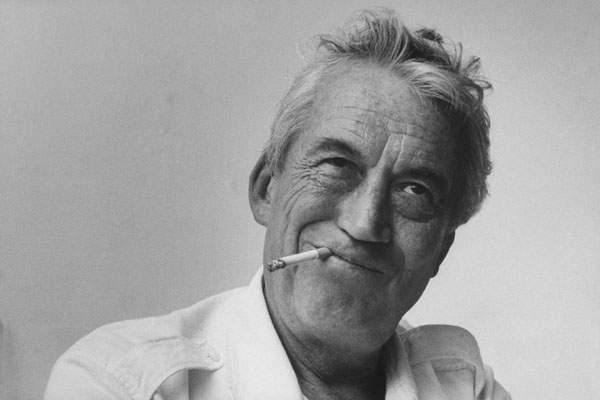

“John Huston doesn’t have a flawless track record as a film director, but few have so perfectly embodied the idea of what a film director ought to be,” writes Nick Pinkerton in his Artforum overview of Let There Be Light: The Films of John Huston, the retrospective running at the Film Society of Lincoln Center through January 11. “With his deliciously drawn-out, folksy baritone and those long, eloquent hands, Huston exuded authority—a quality which other directors were happy to take advantage of.” Among the films in the series featuring Huston as an actor is Chinatown (1974), “the work of Roman Polanski and screenwriter Robert Towne, though [Noah] Cross’s ‘most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place, they’re capable of anything’ would seem to square with the pessimistic worldview visible in Huston’s films.”

“Made after he spent years working as a screenwriter, Huston’s sure-footed directorial debut, The Maltese Falcon (1941), etched with bitter clarity, brought out a compelling complexity in Humphrey Bogart and revitalized the detective genre,” writes Kristin M. Jones in the Wall Street Journal. “Huston went on to direct Bogart in such memorable films as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)—in which the director’s father, Walter Huston, also starred—Key Largo (1948) and The African Queen (1951). Huston also worked with a fine cast, including Sterling Hayden and Marilyn Monroe, for his taut heist film The Asphalt Jungle (1950). The unusual vitality of his many adaptations from books and plays—authors whose work he went on to adapt included Tennessee Williams in The Night of the Iguana (1964) and Rudyard Kipling in The Man Who Would Be King (1975)—reflected his belief that words should contain as much action as images.”

In the L, Justin Stewart recommends The Kremlin Letter (1970), which “delivers everything you want in a Cold War spy thriller, along with a vintage draught of sexism and groovy S&M particular to its moment in time.” And Henry Stewart writes up White Hunter, Black Heart (1990): “In this fictionalized telling of the making of The African Queen (based on a novel by its uncredited rewriter), [Clint] Eastwood performs a sustained, fascinating, campy impression of the larger-than-life John Huston.”

Meantime, the Film Desk has released its second book, John Huston, collecting seven pieces Lillian Ross wrote for the New Yorker. “The essays report on John Huston in New York beginning in 1949, through the Brooklyn shoot of Prizzi’s Honor in 1984, with a stop in Rome for the making of The Bible in 1965. The collection concludes with a piece on Anjelica Huston from the set of her directorial debut Bastard Out of Carolina, reminiscing about her father.”

Update, 1/2: Lukas Foerster on We Were Strangers (1949): “The first half feels like most of the Huston films I’ve seen: Great if somewhat simplistic tough guy cinema marred by various prestige trappings. In the second half, though, the trappings disappear—or maybe rather: become perfectly translucent.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.