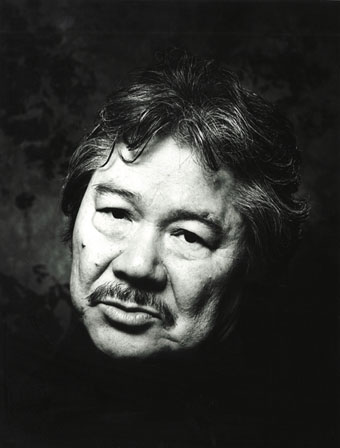

“Word has reached us that the great Japanese director Kôji Wakamatsu has died after being hit by a taxi in Tokyo,” reports MUBI’s Notebook. “2012 has been a banner year for the filmmaker, who saw three new features released this year, including one at Cannes (11/25 The Day Mishima Chose His Fate, our review) and one at Venice (The Millennial Rapture).””Despite having directed over a hundred films in a career that has spanned five decades and also being responsible for, as producer, a number of key works of the Japanese ‘New-Wave’ during the ’60s and ’70s, very little has been written, in English, about independent director/producer Kôji Wakamatsu,” wrote Dickon Neech in a major survey of the filmmaker’s work in 2010 for Eigagogo. Neech proceeds to examine “the years 1963 to 1965, in which Wakamatsu learnt his trade making ero-ductions (a Japanese amalgamation of the words ‘erotic’ and ‘production’) for small film companies in the erotic/pink film market. Chapter two will look at the films produced between 1966 and 1972, when he was at his most prolific and produced his own films (through Wakamatsu Productions), as well as those of several important ‘Japanese New Wave’ directors (such as Nagisa Oshima and Masao Adachi) and becoming the ‘Agent provocateur’ of the leftist Japanese New Wave and underground film/art scene of the time. The next will be an analysis of the films he made from 1973 to 1978 after he was forced to close his production company, and the final section will cover 1979 to the present and his movement from underground ‘pornographer’ to ‘Pink Godfather’, and the respected rebel of Japanese cinema.”Writing for Cinema Scope, Christoph Huber notes that “he realized touchingly personal, increasingly furious, and radical—both in style and politics—dispatches from the spiritual wasteland beneath Japan’s veneer of economic-miracle-sheen, films about the violent insurrection against society’s hypocrisy. Sex and violence remained (not just) genre necessities for the productions of this failed yakuza (and former confectioner) turned revolutionary-filmmaker; anger and anarchy were the driving forces. Controversy was common, and not only as a reaction of reactionaries: Consult your copy of Amos Vogel’s Film as Subversive Art for more-than-ambivalent-accounts.”In 2010, Allan Fish revisited Go, Go, Second Time Virgin (1969) at Wonders in the Dark: “It was shot in four days and represents probably the apex of Koji Wakamatsu’s early shock fests that so delighted the underground devotees and saw him labelled as a pariah to rank with Tekechi in Japanese film infamy. While Yoshida and Oshima were testing the limits of the cinema for the more intellectual audience, Wakamatsu was doing the same on his own cheap, guttural level. Go, Go, Second Time Virgin, if probably surpassed as art by Ecstasy of the Angels, is still probably the place where Wakamatsu virgins are best starting.”

Kevin B. Lee‘s video essay,

“The Hardcore History Lessons of Koji Wakamatsu,”

appeared here in Keyframe in April

Introducing his interview with Wakamatsu for Midnight Eye in 2007, Tom Mes writes that “if the earlier works of this pink film pioneer have conquered their place in the pantheon, it’s less well known that he continues to make movies that touch the sore spots of Japan’s post-war history.” United Red Army, which would appear the following year, is “an engrossing, three-hour plus retelling of the final days of the titular terrorist group and the famed Asama-sanso hostage case, is a film that fills in some of the blanks in the officially sanctioned accounts of history.””1972’s Ecstasy of the Angels in many ways rehearses the self-destruction of United Red Army‘s revolutionary cell,” wrote Budd Wilkins at the House Next Door in February, “albeit played out in a far more sexualized fashion. Interestingly, that film’s writer, Masao Adachi, who would go on to write Caterpillar for Wakamatsu, in the interim gave up screenwriting altogether in order to join the Japanese Red Army, training and living with the group for nearly 20 years in Lebanon, until his arrest and deportation to Japan in 2001. United Red Army and Caterpillar are at bottom studies in hypocrisy, ideologically complementary companion pieces that examine, respectively, the shortcomings of militant student revolutionaries and fervently patriotic (read: jingoistic) nationalists. Both films bookend highly charged fictional recreations within ostensibly objective documentary frameworks.”Updates: While in Cannes this year, Anna Tatarska spoke with Wakamatsu for Keyframe about 11/25 The Day Mishima Chose His Own Fate.In “Underground Japanese Cinema and the Art Theatre Guild,” a 2003 history recently republished by desistfilm, Go Hirasawa writes: “If one considers the intimate relationship of Wakamatsu Production and Sôzôsha, not to mention Adachi’s participation on ATG’s first film Koshikei (Death by Hanging), it is easy to imagine the great influence of the low budget and short shoots of Wakamatsu Production’s pink films on ATG’s 10 million yen film shoots. This relationship ended with Wakamatsu’s production of Ai no corrida (In the Realm of the Senses, 1976). Of course, as a director of the pink film genre, and a representative underground filmmaker one should avoid discussing him simply in terms of his relationship to ATG films but it is also problematic that this relationship is never addressed…. Rather than reminiscing about the good old art films of ATG in a nostalgic and revisionist manner, an investigation of the real meaning of ATG opened up by Koshikei can narrate the revolutionary nature of ATG and the underground, which cut across the cinema and movements supported by Wakamatsu and Adachi.”Via Thomas Groh:

Updates, 10/18: Wildgrounds posts a guide to the “Essential Films of Kôji Wakamatsu” (with clips and so on), and Olivier Père posts a remembrance (in French).Updates, 10/21: A page has been set up on Facebook, “In Memory of Koji Wakamatsu“: “Please feel free to leave a message for Mr. Wakamatsu.”Bruce Weber for the New York Times: “He was expelled from school for fighting and left home for Tokyo, where he became a low-level gangster and was introduced to movie making while working for organized-crime gangs that collected payments from film crews working on their turf. He was arrested and spent six months in prison, where he was tormented by guards, an experience that fueled an enduring distrust of authority. ‘When I got out, I really wanted to get back against the authorities,’ he said in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter in Busan, ‘but I thought if I used violence, I’d end up in prison again. So I decided to use another weapon: film.'”Celluloid Liberation Front for the New Statesman: “Despite the ideological orthodoxy of the Japanese extra-parliamentary left, Wakamatsu never succumbed to its fanatical dérives, articulating instead a cogent critique from within, critical but never dismissive. In Sex Jack (1970) for instance, a group of revolutionary students hiding from the police is joined by a shy outsider willing to help them out only to be mistaken for a spy. Locked away from society in a claustrophobically small apartment, the group enacts the kind of exploitative and abusive practices they ostensibly oppose while covering their cowardice in empty revolutionary rhetoric. Sex here is actively deployed as an allegorical element of the story—highlighting the perverted power relations between the group members, males against females—rather than functioning as a mere front for the political subtext.”Via Nick Pinkerton at Sundance NOW:For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.