When, back in 2012, Il Cinema Ritrovato presented a retrospective of films by Jean Grémillon (1901 – 1959) and Criterion followed up by releasing Eclipse Series 34: Jean Grémillon During the Occupation, I posted a roundup collecting that summer’s wave of nearly ecstatic critical reception. Now New Yorkers have the opportunity to see twelve features and eight shorts on the Museum of the Moving Image’s big screen. The Jean Grémillon retrospective opened yesterday and runs through December 21.

“Even in France, the line on Grémillon is that he’s the most obscure of the country’s major directors,” writes Mike Hale for the New York Times. “Few of his movies made money, and he began and ended his career with documentary shorts. A musician by training and a left-leaning intellectual by disposition, he was a longtime president of the Cinémathèque Française. He sought popular success within the European studio system, though, and there’s nothing abstract or pretentious about the stories of thwarted love and deadly passion that he chose to film.” Remorques (1941) is “the most accessible of Grémillon’s major films, but like much of the rest of his work, it has a core of strangeness, a palpable intensity and a heavy vein of foreboding. If you’re susceptible to this brand of romantic fatalism, his best movies can be transfixing.”

Imogen Sara Smith‘s written an essential survey for Reverse Shot:

A strange, dreamlike movie about a man torn between the worlds of idle wealth and proletarian freedom, Maldone [1928] forms a blueprint for Grémillon’s career, introducing the elements that would recur throughout his works. First, there are landscapes that exert a spellbinding influence on characters: here it is a flat, languid, summery countryside, dominated by big skies and the shimmering light of a canal. In later films it would often be the rocky, storm-swept coast of Brittany or the sea itself in its ever-changing, never-changing vastness. Second, there is a love of work, of the detailed processes of physical labor and machinery. Here, the camera follows grain passing through a threshing machine; elsewhere, it studies the gears and pistons of ships’ engine rooms, the construction machinery of a dam, the repetitive cycles of a printing press, the revolving lens of a lighthouse. Third, music and dance are continually present, embedded in the rhythms and structures of the films but also revealed as the beating heart of communal life.

In the Notebook, Ted Fendt presents his translation of the first part of Mireille Latil Le Dantec’s 1978 essay “Jean Grémillon: Realism and Tragedy,” written when the “time was ripe for a re-evaluation of Grémillon’s films and a resuscitation of his undervalued career…. [T]his article and its follow-up gives us an important view of a French perspective on Grémillon’s work by a very perceptive critic doing the initial heavy-lifting in bringing the proper attention to the filmmaker’s work.”

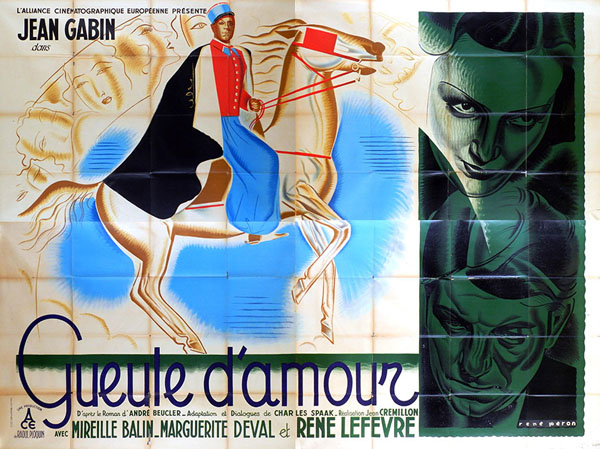

Updates, 11/23: In the Notebook, Adrian Curry‘s gathered “posters for thirteen of his feature films which I present in chronological order from 1928 to 1953. My favorite, beyond that stunning Daïnah la métisse [1932] which I’ve written about before, is the René Péron two-sheet for Guele d’amour [1937].”

Meantime, Jonathan Rosenbaum‘s reposted his 2002 piece on Lumière d’été (1943) and Le ciel est à vous (1944).

Update, 11/29: “Remorques, like a Lynch film, is as absorbed in fulfilling melodrama’s imprimatur as wandering into spaces not normally reserved for the genre, even if the time was not ripe to explode the familiar tropes carefully lined up to garner audience sympathies like a rack of bowling pins,” writes Greg Gerke in the Notebook. “As in La règle du jeu, which Grémillon heavily alludes to in his next film, Lumière d’été, people are alive, but so many are at cross-purposes. Just as in real life tragedies, and quite apart from melodrama, little good will comes from such misplaced emotions.”

Update, 12/14: The Notebook has posted the second part of Ted Fendt‘s translation of Mireille Latil Le Dantec’s essay.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.