One of my own favorite “brushes with greatness,” as David Letterman used to call them, happened on an evening in New York the very day that I’d landed in the City for the first time in far too many years. It was September 2008, the global financial system was collapsing, and there was a sense in the air—at least in the air hovering around my own head—that something as promising as it was unfathomable just might actually come to pass, that post-911 America could well be on the verge of electing a black man by the name of Barack Hussein Obama President of the United States.

So I’m heading out to some address in Tribeca, and as I find the door, I see the lone tall figure of a man leaning against a post looking out into the night, and though I’d never met him, I immediately knew that this had to be Glenn Kenny. Now, as great as Glenn is—and he is—we haven’t quite reached the “brush” yet. I introduced myself, we small-talked, and as I turned to look down the dark street, a silhouette topped with a white flag came whipping around the corner.

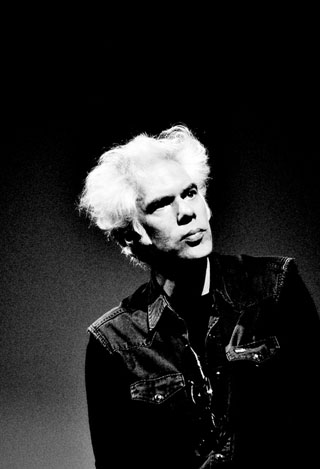

No, I thought. Can’t be. But as he approached at a remarkably rapid clip, sure enough. Jim Jarmusch, walking right on up into our space, because, of course, he and Glenn knew each other. Glenn introduced us, and as we shook hands, I tipped forward slightly, signaling respect without bowing and scraping, and said, “Very pleased to meet you” with just a hint of emphasis on the “Very.” A few more words and nods, and Jim Jarmusch went on inside. And I thought to myself: “Well done.”

Jim Jarmusch is 60 today, and chances are, he’s in post-production on his vampire movie, Only Lovers Left Alive, which’ll be featuring Tom Hiddleston, Tilda Swinton, Mia Wasikowska, John Hurt and Anton Yelchin. Shooting wrapped in Germany last fall.

Any quick roundup of appreciation of Jarmusch’s work has to begin with Jonathan Rosenbaum, a friend of the filmmaker who, after all, wrote the book on Dead Man (1995). In 2004, JR opened a piece for the Guardian on Coffee and Cigarettes (2003) with this: “It’s an enduring paradox of Jim Jarmusch’s work as a writer-director that, even though his films may initially come across as a triumph of style over content, in the end it turns out to be a victory of content over style. Maybe it’s the ultimate paradox of minimalism: the less your work does and is, the more these things matter.”

It’s a splendid overview of the oeuvre. Start there. Here are a few other places to go: Reverse Shot‘s big 2005 Jim Jarmusch Symposium; J.D. Lafrance‘s contribution to the Senses of Cinema Great Directors Database; J. Hoberman‘s 2007 piece for Criterion on Stranger Than Paradise (1984); Luc Sante, also for Criterion, on Down by Law (1986); Alan Jacobson in Bright Lights on Mystery Train (1989); Thom Andersen, Paul Auster, Bernard Eisenschitz, Goffredo Fofi, and Peter von Bagh, all for Criterion, on Night on Earth (1991); Marco Lanzagorta, Ryoko Otomo, and Fiona Villella, all in Senses, on Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999); Jeremiah Kipp in Slant on Broken Flowers (2005); and Gavin Smith‘s interview for the cover story of the May/June 2009 issue of Film Comment—the occasion was the release that year of Limits of Control.

Saluting him on his 60th in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung is Verena Lueken.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.