“The term Afrofuturism was first coined by writer Mark Dery in his influential 1994 essay ‘Black to the Future’ [PDF] to provide a name for work which addresses black themes through science-fiction and technoculture lenses,” begins Ashley Clark, who’s curated Space Is the Place: Afrofuturism on Film, the series that opened at New York‘s BAMcinématek yesterday and runs through April 15. “Descriptions of it vary from Afrofuturist author Ytasha Womack, who calls it ‘elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-Western beliefs,’ while others, such as Afrika Bambaataa, take a more gnomic approach: ‘Afrofuturism is dark matter moving at the speed of light.'”

For the Guardian, Clark writes up five highlights from the program, while at BAM’s blog, he shows us ten “Afrofuturist Music Videos“: “One of the key figures in heralding the resurgence of Afrofuturist aesthetics is the ‘Archandroid’ Janelle Monae, though there is a strong lineage of musical Afrofuturism, including—but not limited to—Jimi Hendrix, Sun Ra, Miles Davis, Parliament-Funkadelic, Afrika Bambaataa, the pioneers of Detroit Techno, and Missy Elliott.”

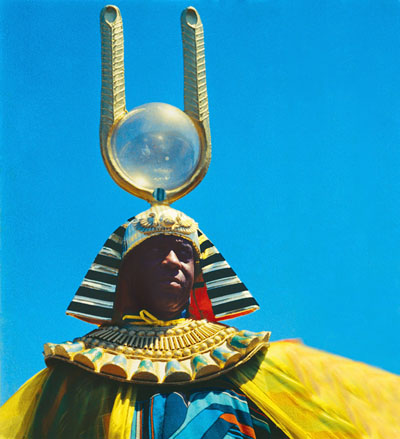

“Musicians are key,” agrees J. Hoberman in the New York Times, “notably the avant-garde jazz composer and bandleader Sun Ra (born Herman Poole Blount in Birmingham, Ala.), who recast himself as an extraterrestrial and performed in appropriately fanciful costumes, and the similarly flamboyant self-invented funk maestro George Clinton, the leader of the band Parliament, whose 1975 album, Mothership Connection (on which he speaks as the Star Child addressing the ‘citizens of the universe’), is a crucial text. The Brooklyn Academy series is titled after a Sun Ra production—in Space Is the Place, he stars as himself, beamed to Earth from Saturn to wage a war of mind control against the satanic supernatural pimp known as the Overseer. Delivering a message to black America, Sun Ra declares, ‘Time has officially ended,’ and later announces, ‘Everything you have desired on this planet and never received will be yours in outer space.'”

Writing for Artinfo, Craig Hubert argues that the “centerpiece” of the series is The Last Angel of History (1997). “Directed by John Akomfrah (as a member of Black Audio Film Collective), the film uses a panoply of voices (critics [Kodwo] Eshun and Greg Tate; novelists [Samuel R.] Delany, [Octavia] Butler, and Ishmael Reed; musicians Derrick May, Goldie, and Juan Atkins, to name only a few) to expand on the idea of Afrofuturism through the possibility of three different origin points,” dub producer Lee “Scratch” Perry, George Clinton and Sun Ra. Further reading: Aaron Sandhu‘s “How did Sun Ra’s Space Is the Place influence the Afro-American diaspora and Afrofuturist counterculture?”

Possibly NSFW, but hey, it’s the weekend

“Explicit or not, eroticism lurks in every scene of Walerian Borowczyk’s films,” says Violet Lucca at the top of the video essay Film Comment‘s posted. You’ll find the bulk of the roundup on the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series Obscure Pleasures: The Films of Walerian Borowczyk (through Thursday’s) in an entry posted the other day, but let’s make note not only of the new audiovisual essay but also of Nick Pinkerton‘s piece for Artforum. Borowczyk’s films “are among the purest instances of fetishist cinema that I know,” he writes. “Although ‘Boro’s’ movies certainly abound with erotic fixations and substitute phalluses—the altar candlesticks and zucchinis in the ‘Thérése Philosophe’ episode of Immoral Tales (1973), the bedpost in The Beast (1975), the catalogue of verboten vintage erotic paraphernalia in A Private Collection (1973)—I use this phrase not with a solely sexual connotation, but with the broader meaning of fetish: the imbuing of inanimate objects with human or extrahuman power and presence.”

Back to BAM, back to Film Comment, and more from Nick Pinkerton, who interviews the subject of a career overview at BAMcinématek, Overdue: James B. Harris, on through Monday. Harris produced Stanley Kubrick‘s The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957) and Lolita (1962) before setting out on his own as a director with The Bedford Incident (1965). “And while Harris has remained a cult item in the U.S.,” notes Pinkerton, “he has been championed abroad, particularly in France, where Some Call It Loving [1973] recently enjoyed a successful commercial re-release, alongside a career retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française.”

Chicago. “Running each Tuesday through spring, Doc Films presents Frederick Wiseman: An Institution, ten features from the documentary elder’s expansive library,” writes Ray Pride for Newcity Film. The program’s been curated by Chicago Reader regular Ben Sachs and his wife, Kat, and Ray has a few questions for Ben “about the intentions of the series, shown entirely on 16mm.”

So these particular films are from Wiseman’s substantial back catalogue?

For a while now, I’ve considered Wiseman to be America’s greatest living filmmaker. In our essay for the Doc Films website, Kat and I compare him to Warhol and Bresson; and like them, Wiseman has the power to transform hard and fast reality into something wholly cinematic. His movies, for us, represent cinema in its purest state.

San Francisco. “YBCA’s April series Dark Horse: Film Noir Westerns provides eight prime vintage examples of Hollywood locating high conflict and emotional torment in that traditionally least-complicated setting for cinematic melodrama, the Old West,” writes Dennis Harvey at Eat Drink Films. “From the medium’s earliest days, the western was a genre in which a wholesome, elemental morality ruled—bad guys wore black hats, good guys wore white…. But after World War II, the disillusionment and cynicism that fueled the explosion of tough crime mellers that we now call film noir also crept into other genres.” The series opens tomorrow with a double feature, Robert Wise‘s Blood on the Moon (1948) and Budd Boetticher‘s The Tall T (1957) and runs through April 26.

Los Angeles. Just a reminder, a few days after Max Goldberg‘s piece here in Keyframe, that on Monday, REDCAT presents The Films of Gregory J. Markopoulos.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.