“At once sublime and ridiculous,” begins Steve Dollar in the Wall Street Journal, “the Italian giallo film is one of the cinema’s most dizzying indulgences. Emerging in the early 1960s, the genre fed off Hitchcock, film noir and horror, inspiring emulations both sleazy (the slasher flick) and stylish (Brian De Palma’s icy thrillers), and more recently spawning such festival sensations as Amer and Berberian Sound Studio—explicit homages to the surreal, erotic imagery and hypnotic soundtracks that gave the form its uncanny allure.” The Anthology Film Archives series Giallo Fever! “revives 10 gialli, overripe pulp fictions transformed into suspense films that made iconic use of black leather, mile-wide eyeballs, convoluted plots, American B-movie actors, terrible dialogue dubbing, and throbbing electronic scores that haunted the ears long after the blood was drained from the screen.”

“The term ‘giallo‘—Italian for ‘yellow’—comes from the long-running Il Giallo Mondadori mystery paperback imprint, distinguished by their yellow covers,” explains Nick Pinkerton in the Voice. “Like the spaghetti westerns, whose popularity paralleled the giallo‘s, and which used many of the same directors and actors (Franco Nero, Tomás Milián, Fabio Testi), giallo was found in translation, its personality derived through pronouncing a foreign genre vocabulary with an Italian accent. Where the spaghettis transposed native political resentment to the American frontier, gialli drew on the hysteria resultant as parochial Italian conservatism collided with an ongoing upheaval in public sexual mores, abetted by sex-sells commercialism.”

“Despite the rather strict narrative structure most of these directors follow, there is a wide diversity in their implementations,” writes Benjamin Schultz-Figueroa in his overview of the series for the Brooklyn Rail. “As any jazz musician or genre-studies film student can tell you, there is creativity and innovation involved in playing a standard.”

Time Out‘s David Fear notes that the series opens today “with a Mario Bava double shot: 1963’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much (Thu 20, Sun 23 and Sept 29) and 1964’s Blood and Black Lace (Tue 25, Sep 30). Largely considered to be the first proper giallo movie, the former runs Letícia Román through the scream-queen paces as a tourist who witnesses a murder. Bava’s black-and-white whodunit pays homage to the genre’s literary roots—his heroine is introduced reading a yellow-covered crime novel. Black Lace then sets the bar for every giallo that followed: the black-gloved serial killer; the Grand Guignol homicides; the borderline misogyny; and the hyperexpressive use of color—notably red.”

“If Fritz Lang made more color films (and worked super speedily or took more drugs, perhaps) it would look like these,” writes Miriam Bale for the L, where she, too, recommends The Girl Who Knew Too Much: “It’s a masterpiece homage to Hitchock, which takes the irony in the Master’s work a little more playfully and pushes the tension/irresolution further until the whole film becomes a wonderful, titillating joke.” And on a related note, Sean Axmaker reviews new releases on DVD and Blu-ray of three films by Mario Bava, Black Sunday (1960), Lisa and the Devil (1973), and Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1968).

In MUBI’s Notebook today, David Cairns reviews a “forgotten” giallo that’s not in the series, but still: Sauro Scavolini’s Love and Death in the Garden of the Gods (Amore e morte nel giardino degli dei, 1972) “is a lovely test case for how far the giallo could stray from its sources of inspiration and still be true to itself.”

One more thing: giallo fever is also a blog, albeit one unrelated to the Anthology series.

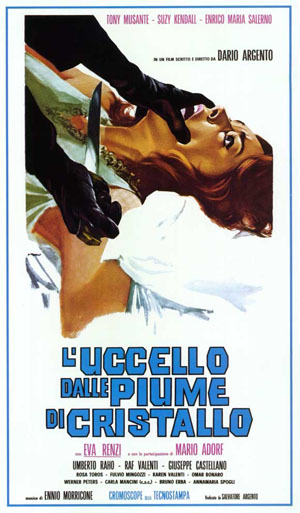

Update, 9/23: “More than plot or acting, it is ambience that these films evince best,” writes Ara J. Merjian for Artforum. “Far scarier than the act of murder in [Dario] Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) is the view of its site: an empty modern art gallery at night, its isolated objects illuminated by a stark and sour light. If Argento’s work helped push the giallo’s proverbial envelope, the genre has always been intrinsically and unabashedly pluralistic, drawing on both high and low culture. Pastiche of—and contamination by—other styles constitutes the giallo’s very quiddity, inflected as it is by horror, mystery, melodrama, noir, thriller, slasher, and seemingly infinite cinematic rubrics. The terrors and pleasures of this uniquely Italian strain of filmmaking have not so much faded since the ’70s as merged imperceptibly with other forms and formats.”

Update, 9/26: In MUBI’s Notebook, Ben Semington has clips from and commentary on Amedeo Tommasi’s soundtrack for Pupi Avati’s The House with the Laughing Windows (1976).

Update, 9/27: David Cairns on another “forgotten” giallo, Femina ridens (1969): “Look, I don’t really care if this is a giallo at all: it is a mod psycho-thriller (as gorgeous as Clouzot’s La prisonnière and Bava’s Diabolik), and the direction the plot takes owes some kind of debt to Les diaboliques, a key text in the development of the genre, I’d say. Director [Piero] Schivazappa shows a keen eye and a great sense of visual rhythm, aided by Stelvio Cipriani’s hip score: together they turn the final sex confrontation into a Leone gunfight, complete with big eye close-ups, blaring trumpets and twanging electric guitar.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.