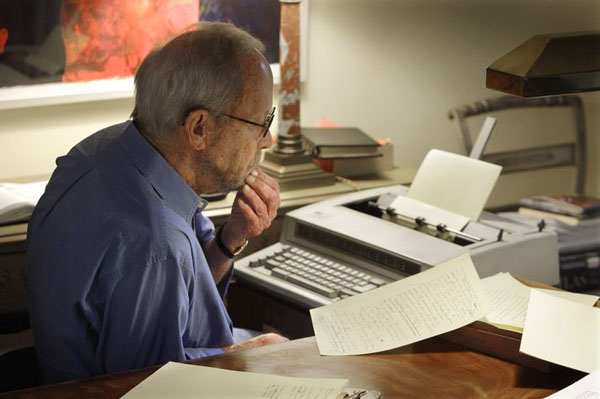

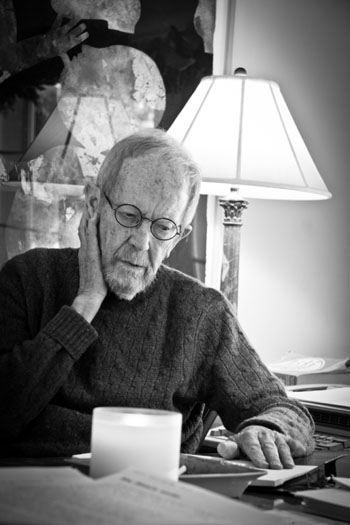

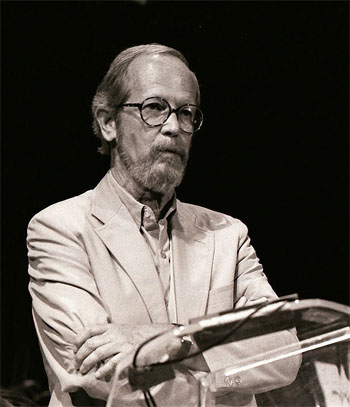

“Elmore Leonard, the author best known in the film world for the feature adaptations of his works Get Shorty, Out of Sight, and Rum Punch (which was filmed as Jackie Brown), has passed away at 87, three weeks after suffering a stoke,” reports Nigel M. Smith at Indiewire. “Gregg Sutter, Leonard’s researcher and webmaster, broke the news of Leonard’s passing on the novelist’s Facebook page, writing that he died surrounded by family in Detroit, the city he’s called home since 1934.”

The Playlist‘s Kevin Jagernauth notes that “Stephen King called him the ‘the great American writer’ and last year the author took home the National Book Award Medal for Distinguished Contribution.” And he adds that Quentin Tarantino once told Erik Bauer: “Well, when I was a kid and I first started reading his novels I got really caught up in his characters and the way they talked. As I started reading more and more of his novels it kind of gave me permission to go my way with characters talking around things as opposed to talking about them. He showed me that characters can go off on tangents and those tangents are just as valid as anything else. Like the way real people talk. I think his biggest influence on any of my things was True Romance. Actually, in True Romance I was trying to do my version of an Elmore Leonard novel in script form. I didn’t rip it off, there’s nothing blatant about it, it’s just a feeling you know, and a style I was inspired by more than anything you could point your finger at.”

Elisabeth Donnelly in the Los Angeles Times: “Leonard’s awards include the Grand Master Edgar Award in 1992, the F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Award for outstanding achievement in American literature in 2008, the PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009, (for which he was complimented for his ‘uncanny ear for crooks, cops, and babes’) and the National Book Award Medal for Distinguished Contribution in 2012. In his widely circulated rules of writing, Leonard said, ‘Never open a book with weather; avoid prologues; keep your exclamation points under control; use regional dialect sparingly; avoid detailed descriptions of characters, places, and things; and try to leave out the part the readers tend to skip.’ Most important, however, he said, ‘if it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.'”

“To his admiring peers, Mr. Leonard did not merely validate the popular crime thriller; he stripped the form of its worn-out affectations, reinventing it for a new generation and elevating it to a higher literary shelf.” Marilyn Stasio in the New York Times: “Reviewing Riding the Rap for the New York Times Book Review in 1995, Martin Amis cited Mr. Leonard’s ‘gifts—of ear and eye, of timing and phrasing—that even the most indolent and snobbish masters of the mainstream must vigorously covet.’ As the American chapter of PEN noted…, his books ‘are not only classics of the crime genre, but some of the best writing of the last half-century.'”

Updates: “Elmore Leonard is perhaps the most cinematic novelist writing in the English language,” the Atlantic‘s Christopher Orr wrote in a 2004 review of The Big Bounce. “This is partly due to his usual subject matter—strong men and beautiful women on the edge of the law—but still more to the fact that his books read very nearly in real-time. Unlike most crime writers, for whom no physical or emotional detail is too small, Leonard has an extraordinary gift for concision: In any given scene he tells you just enough for the scene to play, and nothing more. As a result, his novels tend to go by in a happy, imagistic blur that feels more like a pleasant moviegoing experience than most actual trips to the multiplex.” Via Spencer Kornhaber.

Glenn Kenny recalls going to the party after the premiere of Jackie Brown (1997) and bumping into Abel Ferrara: “Feeling sufficiently emboldened by the festive vibe, I asked Ferrara how he, who had made a movie, the ill-fated 1989 Cat Dancer, from an Elmore Leonard book some years prior to Tarantino’s film… thought Quentin had done by the maestro. ‘He did great. Got the tone just right. Did you see Get Shorty?’ He rolled his eyes. ‘God. So studio-ized. Every time they shoot Travolta from a low angle they’ve got the fucking key light giving him a halo.’ … When I was just learning to read seriously, a lot of literary types were bemoaning, and not without reason, the absence of Chandler and Hammett. It took me a little while to figure out that while those guys were indeed worth mourning, I myself was in fact living in a golden age of genre fiction, because Donald Westlake/Richard Stark, Charles Willeford, George V. Higgins, and Elmore Leonard were alive and kicking and writing.”

“Walker Percy was a big Elmore Leonard fan,” noted Bill Morris at the Millions in 2010. “Way back in 1987, during the high noon of a career that has now reached its rich and plummy twilight, Percy asked: ‘Why is Elmore Leonard so good?’ Percy answered: ‘He doesn’t stick to the same guy in the same place.’ And: ‘You begin to notice his prose, the way he moves people around. People get shot in dependent clauses.’ And: ‘The snap and crackle of the dialogue is something to hear.’ To wit: ‘(Leonard) often drops the word “if” in dialogue—and uses hardly any conjunctions. “I had a tire iron we could find out in ten minutes.” This sentence could use an “if” and a comma and would be worse for it. Yes, Mr. Leonard knows what he’s doing.'”

At Twitch, Todd Brown looks back on a “Dozen Screen Essentials From Elmore Leonard.”

David Simon: “He leaves behind narratives that make us think harder about the human condition, not to mention all of our presumptions about how our society actually functions—or doesn’t.”

“His earliest fictions, whether short stories or full-length novels, were westerns, because, he later confessed, he liked cowboy movies and he hoped to sell to Hollywood,” writes Nick Kimberley in the Guardian. “It was not long before Hollywood took note with The Tall T (1957), directed by Budd Boetticher, and 3:10 to Yuma, based on a 9,000-word story published in 1953, and filmed by Delmer Daves in 1957…. Surprisingly, given his talent for dialogue, he wrote few movie scripts: among the more notable were The Moonshine War, for Richard Quine in 1970 (he later ‘novelized’ his own screenplay), and John Sturges’s Joe Kidd, in 1972. The latter starred Clint Eastwood, a passable incarnation of Leonard’s self-contained heroes.”

Leonard “recently had his 1978 crime novel The Switch adapted into a movie titled Life of Crime,” notes Amy Kaufman in the LAT. “It is scheduled to debut at the Toronto International Film Festival next month. The picture centers around two criminals (John Hawkes and Yassin ‘Mos Def’ Bey) who kidnap the wife (Jennifer Aniston) of a wealthy real estate developer for ransom. Unfortunately, the rich man (Tim Robbins) doesn’t want to pony up for his wife because he’s in love with his mistress (Isla Fisher). The movie, on which Leonard served as an executive producer, is set to close the 11-day festival on Sept. 14.”

“Tarantino didn’t just adapt him for one movie, he learned a lot about dialogue from reading him,” writes Matt Zoller Seitz for Vulture. “So, it would appear, did the Coen Brothers, and Vince Gilligan of Breaking Bad, and everyone who ever wrote for The Wire—many of them crime novelists who couldn’t help but be influenced by Leonard, because you can’t not be; that’d be like trying to write a musical without being influenced by Stephen Sondheim, or act without being influenced by Marlon Brando, or sing torch songs without being influenced by Billie Holliday or Frank Sinatra. Leonard was the Man, and always will be.”

At the Dissolve, Scott Tobias, Noel Murray, Nathan Rabin, Tasha Robinson, and Matt Singer discuss Leonard’s career, “particularly as it connected with the many movies made of his books over the years.”

Updates, 8/21: The Los Angeles Review of Books has posted Jon Wiener‘s 2000 interview.

“For a White guy, he certainly knew how to sound convincingly like the Black dudes who populated many of his novels,” writes Odie Henderson at RogerEbert.com. “He captured the cadences of their speech, and did so without stereotype. His Brothers sounded like the guys I heard on the street in my old neighborhood; his cops sounded like cops I knew.”

“He sold more than 20 of his novels or short stories to Hollywood, and wrote half a dozen screenplays himself,” writes the Telegraph‘s David Gritten. “But in the transition from page to screen, something often got lost…. Part of the reason for Leonard’s problems with Hollywood was surely that the characters he wrote are nuanced and complex; they are never wholly good nor wholly bad, no matter which side of the law they stand. Films, in contrast, tend to reassure audiences by categorizing characters immediately. It’s also the case that Leonard’s stories emerged from the natures of his characters rather than from action or events; his great strength was dialogue, from which his plots would emerge. Most films, in contrast, are plot-driven from the start.”

Updates, 8/23: At the Stacks: “Elmore Leonard Wrote Great Opening Lines. Here Are All Of Them.”

Film Comment has posted abridged excerpts from an interview by Patrick McGilligan that appeared in the March/April 1998 edition.

Following a marvelous riff on Leonard’s style, the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane writes, “I met Elmore Leonard once, and spent an hour with him. He was courteous and soft-spoken, and I cherish the first edition of Freaky Deaky that he inscribed for me. Of himself, as expected, he gave little away, and the effort to fix him now, in my memory, is an almost impossible task. When I discovered in the diaries of Sir Alec Guinness that the great actor was a fan of Leonard, and that he took Out of Sight on vacation one year, the link made perfect sense. Each man was skilled in self-effacement and immune to glamour, reserving all his bravado and wits for the professional arena; you can picture Leonard, like George Smiley, eavesdropping tacitly from the fringes of a room.”

“If you haven’t read an Elmore Leonard novel, now would be a good time to do that,” advises Jonathan Segura, writing for the Paris Review. “I normally tell people to start with The Hot Kid, which merges the two genres he owned: westerns and crime. But it’s not ‘vintage’ Elmore Leonard, in that it takes place over a few years instead of a much more compressed few days or weeks, and it isn’t strictly about a few people in a hard situation making mostly bad choices. Vintage Elmore Leonard is that: some characters and a problem that only gets bigger, and it’s all powered by some of the best dialogue you’ll ever read. Really.”

Updates, 8/24. At Vulture, Sean Howe tells the story—or at least what’s known of it—behind the non-making of the adaptation of LaBrava. Scorsese was attached for a while, Coppola was interested, and eventually it fell into the hands of Hal Ashby. Again, who knows what actually happened, but it does seem that the one man keeping it from actually getting made as the years flew by was the guy originally interested in playing the lead, Dustin Hoffman.

Listening (19’39”). Fresh Air remembers Leonard.

Update, 8/25: “The son of late author Elmore Leonard has said he hopes to complete his father’s last novel,” Blue Dreams, reports the BBC.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.