Obviously, not everyone is going to love any given film, but since its premiere at Cannes, where it won the Palme d’Or, Michael Haneke‘s Amour has screened to appreciative audiences at a slew of festivals, including Toronto and New York, it’s won the International Federation of Film Critics’ (FIPRESCI) Grand Prix for Best Film of the Year, it’s opened to raves in the U.K., and now that the listing and awarding season is here, it’s cleaning up: #3 in Sight & Sound‘s poll of over 90 critics, “Best Foreign Language Film” for critics’ organizations in New York, Washington, and Boston, and best-film-period for the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. To dig a bit closer to an answer to the question raised in this entry’s title, we’ll want to sample the reviews that have appeared since the initial roundup in May.

We can begin by noting that there’s a new issue of Senses of Cinema out, and Amour is front and center. In his editorial, Rolando Caputo considers the “odd event” that is the European Film Awards, where Amour “made a clear sweep,” winning best film and director as well as actor for Jean-Louis Trintignant and actress for Emmanuelle Riva: “Haneke is the most consistent chronicler of the historical vicissitudes of the European bourgeoisie over the course of the 2oth and early 21st century. If there is such a thing as a ‘European film,’ right here and now, he may be its best exponent.”

Which leads us for the moment to the new Brooklyn Rail and to Jaap Verheul, who calls Haneke “the flag-bearer of the continent’s art cinema… The economic and political relationship between the Austrian, French, and German film industry and the pan-European audiovisual market contributes in no small part to the fashionable ‘Europeanness’ of Amour and its auteur, for Haneke cannot be identified as specifically German, Austrian, or French, or as belonging to a particular moment or movement in filmmaking…. Haneke’s films not only approve of a unified Europe, they also uphold it as a utopia that emanates from the successes and failures of European unification since the Second World War.” And “while most filmmakers from the continent are often confined by their national and cultural citizenship, Haneke’s films transcend specific national identities, and Amour is no exception.”

But back to Senses, and before I turn to Roy Grundmann‘s essay “inside” the issue, I should note that the film won’t open in the States for another week or so, and while I’ll avoid quoting snippets that contain what might be considered spoilers, some of the pieces I link to are loaded with them. Including Grundmann’s, but we’re fine with his opener: “Once again, Michael Haneke gives us a story about Georges and Anne, the bourgeois couple that, in various incarnations, has populated his films since the 1980s. In Amour they are two dignified octogenarians who live in a spacious Paris apartment, enjoying their autumnal lives as music lovers and patrons of the piano arts. Amour‘s couple stands in sharp contrast to the Georges and Anne of Haneke’s earlier films, most of who suffer from various forms of alienation that, in Haneke’s universe, are characterized by a condition of ‘glaciation.’ Having been married for most of their adult lives, their relationship continues to be determined by warmth, intimacy, and honesty. Yet Haneke’s portrayal of their mellow love that, somewhat surprisingly, is just as sustained and detailed as his previous studies of violence and dysfunction, is put to the test by an illness that Anne suffers not long into the film and that leaves her gradually but ineluctably incapacitated. It is this test of their love—and even more, the radical mutation their love undergoes when put to this test—on which Amour pivots.”

Towards the end of an analysis of several of Haneke’s films in the London Review of Books, Gilberto Perez, too, seems at least mildly surprised that Haneke’s given Amour “a happy ending of sorts.” Which, again, we’ll quote no one elaborating on here. But: “The threatened privacy of the bourgeoisie is a theme as central to Amour as it is to Caché or Funny Games…. Like Antonioni, a filmmaker he admires, Haneke puts us in the position not of an intimate but of a stranger who knows only what can be gathered from appearances, fragments of narrative that are sometimes attentively drawn out, sometimes elliptically cut short. The couple’s daughter (Isabelle Huppert) comes to visit, and as she talks to her father we realize that some time has passed. Anne, after her stroke, has been in hospital for an operation that has failed. She returns to the apartment in a wheelchair and asks Georges to promise never to take her back to hospital. He keeps his promise. Anne is increasingly unwilling to receive visitors, to let them see her in her worsening condition, and even fends off her daughter. This story of love, face to face with death, is also a story of isolation.”

“[C]laims that Amour represents a marked departure or maturation strike me as fairly dubious,” writes Calum Marsh in Slant. “Even the film’s title, which might reasonably apply to the honestly loving relationship at the center of the narrative, is deployed with a perfidious smirk, its title card appearing as it does the very moment a corpse is revealed. Rest assured, this isn’t the work of a newly moral or humanistic filmmaker, but another ruse by the same unscrupulous showman whose funny games have been beguiling us for years.”

“Whether pondering national racial legacies (Caché), media saturation (Benny’s Video), the blood sport of contemporary movies (Funny Games), the apocalypse (Time of the Wolf), or the seeds of fascism (The White Ribbon), the Austrian cinematic taskmaster engages in narratives and aesthetics that seek to shock or discomfit the viewer,” writes Michael Koresky in Reverse Shot. “Haneke is a genre filmmaker at heart, no matter how hard he might wish to deny it. Air of sober intimacy notwithstanding, Amour… is a horror film. Following the devastating final months experienced by a dying woman and more specifically the loving husband who has taken it upon himself to care for her, it is meant to appall and terrorize, to evoke unpleasant sensations, to leave its audience suspended in dread, and ultimately, as is the primal goal of horror, to elicit catharsis.”

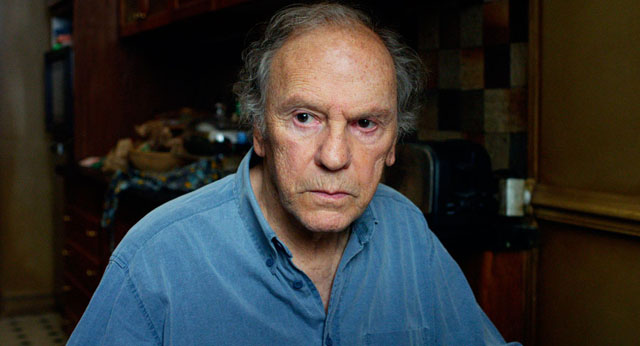

“Haneke has always possessed the cruel streak of a harsh, ruler-wielding pedant,” writes Michael Sicinski for Cargo. “True, he has made some rich, emotionally complex films, Code Unknown chief among them. But over time, it’s become apparent that he has absorbed some wildly skewed lessons from the Book of Adorno. Haneke truly believes that the masses are asses, and only by submitting to the rectitude of his cinematic vision might we possibly be saved, or at least corrected…. So, what is really going on with Amour? Certainly, it has two of our finest living actors at its core, even if Riva’s turn (under Haneke’s direction, no doubt) is given to certain showy fillips and over-articulated ‘subtleties.’ In truth, it is Trintignant, hunched and haggard, suppressing anger through duty, who delivers a truly career-capping performance…. But is this what seems to make Amour a cut above the much-maligned deathbed film, which is always presumed guilty of schmaltz by dint of its subject? No, a good deal of what Haneke has going for him is sheer ugliness. Amour (which I saw presented in 4K DCP) is the flattest, most anti-aesthetic film this director has ever produced. Aside from a few exteriors and a concert scene, it takes place almost exclusively in the couple’s Paris apartment, which is shot by Woody Allen d.p. Darius Khondji as a drab smudge of mustards and umbers, shelves and paneling. Light and shadow have no impact in this film. Visual information is purely functional. And this seems to be part and parcel of Haneke’s crushing seriousness. Aesthetic concerns, he seems to say, would be a bourgeois indulgence, while we, the master class, are charged with gazing into the Face of Death.”

Or, as Christoph Huber‘s put it in Cinema Scope, Amour is “a film that comfortably ushers its dwindling target audience towards its eventual demise.”

So we have our answer to the opening question. Still, when Amour finally opens in the States, we’ll be hearing more from its admirers (and, for what it’s worth, I count myself among them), and for now, I refer you to more reviews from Nigel Andrews (Financial Times, “pitiless, mordant, touching, humane,” 5/5), Catherine Jessica Beed (desistfilm), Peter Bradshaw (Guardian, “a passionate, painful, intimate drama to be compared with Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage,” 5/5), Dave Calhoun (Time Out London, “a masterpiece,” 5/5), Roger Ebert (Chicago Sun-Times, “one of the best films of the year”), David Ehrlich (Movies.com, “cinema at its most compassionate”), Steve Erickson (Gay City News, “Trintignant’s performance is one of the best the octogenarian actor has ever delivered”), David Fear (Time Out New York, “emotionally resonant”), Philip French (Observer, “Amour will, I believe, take its place alongside the greatest films about the confrontation of ageing and death, among them Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Kurosawa’s Living, Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, Rosi’s Three Brothers and, dare I say it, Don Siegel’s The Shootist“), Kurt Halfyard (Twitch), David Jenkins (Little White Lies, “Haneke’s answer to the weepie”), Nick Pinkerton (Voice, “Haneke’s distance is meant, perhaps, to allow viewers space to contemplate their own mortality; I found myself using it to remember movies which had something more to them”), Anthony Quinn (Independent, “Who would have thought this filmmaker had such tenderness in him?,” 4/5), Tim Robey (Telegraph, “modulates from tonal disquiet to a profound and moving calm,” 5/5), Jonathan Romney (Independent, “a profound and bracing experience—and one that, like it or not, will tell you more about your life (yes, yours, sooner or later) than you’d imagine cinema would ever dare,” 5/5), Emma Simmonds (Arts Desk), Scott Tobias (AV Club, “a bracingly unsentimental film, but it isn’t heartless,” A-), Bob Turnbull (“A movie I have no plans to ever revisit”), Catherine Wheatley (Sight & Sound, “a delicate and tender elegy”), Neil Young (Tribune, “Amour isn’t really so much more than a high-class TV movie”), and Stephanie Zacharek (Film.com, “an exceedingly tender film,” B+).

Interviews with and profiles of Haneke: Stephen Applebaum (Independent), Peter Conrad (Observer), Philip Horne (Telegraph), and Tom Shone (New York). Alexandra Marshall tells the story of the film’s making in the Hollywood Reporter, and the Guardian‘s Xan Brooks talks with Riva and Trintignant.

Updates, 12/12: “Haneke’s dry-eyed, unsentimental approach makes what would have been, in someone else’s hands, an agonizing ordeal a little more bearable, allowing for moments of relief when a semi-symbolic pigeon finds its way into the house, or a jolt of horror in a nightmare sequence,” writes Alison Willmore for Movieline. “But the clinical distance Haneke manages so well also makes the film feel like a beautifully crafted but calculated exercise, one gentler and touched with more warmth than his earlier films, but still meant to be a shrewdly knowing knife to the viscera.”

For David Thomson, writing in the New Republic, “now at the end of the year comes a masterpiece, not just the best of the year, but one of the best ever: Michael Haneke’s Amour.”

Updates, 12/23: “A masterpiece about life, death and everything in between,” declares Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “Viewers acquainted with Mr. Haneke’s work may find Amour too cold, cruel even, and its depiction of suffering a punishing, familiar gesture from a director who’s long been interested in transforming spectators from simple consumers into critical thinkers. There are certainly arguments to be made about whether movie-watching is ever simple or noncritical. Yet there’s another point to be made here, namely that all the violence in Amour is crucial to Mr. Haneke’s rigorous, liberatingly unsentimental worldview, one that gazes on death with the same benevolent equanimity as life.”

“There are very few films in which, with heightened awareness, you cling minute by minute to an inexorably dwindling life, even as you wait for the finality of its ending,” writes J. Hoberman at Artinfo.

“The Haneke film Amour recalls most strongly is his first, 1989’s The Seventh Continent, another straightforward march toward death, albeit of the meticulously planned variety,” suggests Scott Tobias at the AV Club. “The earlier film follows a couple that resolves to dismantle and extinguish their lives (and their child’s), while Amour approaches it from the grueling perspective of a man who has to sustain a life that will end just as surely…. But that title, Amour, couldn’t be more sincere…. Haneke being Haneke, Amour is still a bracingly unsentimental film, but it shouldn’t be mistaken for heartless.”

“Even when it’s so painful you need to look away for a moment, Amour abounds in simple moments of intimacy, tenderness, and even joy,” writes Slate‘s Dana Stevens. “At a late stage of his wife’s decline, as Georges sits on the edge of Anne’s bed sharing a memory she seems at first only to half-understand, she places her still-working hand on one of his and with difficulty enunciates the words ‘C’était bien’—it was nice. Immediately we understand: She’s referring not only to the story her husband is relating, but to the whole of their life together—a life whose richness Haneke alludes to only with the most minimal gestures.”

“Amour makes the perfectly fine Julie Christie film Away From Her look like an ad for a swank retirement home, but it will stir your soul,” writes Ella Taylor for NPR. “If you’ve seen someone you love through their dying, it may burn you up—but in an illuminating way.” Georges “retains enough spirit not to mince words with any would-be advisers. ‘Your concern is of no use to me,’ he tells his increasingly distraught daughter. That might be the entire Haneke oeuvre talking.”

“No director works as single-mindedly to punish his audience—to make it pay double for every voyeuristic pleasure,” writes New York‘s David Edelstein. “You could argue in this case that his cruelty is a form of compassion. It’s one reading. In outline, Amour evokes David Cronenberg’s The Fly, which was influenced by the last months of the director’s father’s death from a wasting disease. In Cronenberg’s scenario, the horror of the protagonist’s degeneration is tempered by the love of his girlfriend: She is afraid, ‘very afraid,’ but she doesn’t turn away. When his agony reaches its zenith and she splatters what’s left of his human brain on the wall, the moment is positively operatic. Haneke is nowhere near as romantic: His static camera gazes on the couple’s anguish with clinical dispassion. It’s quite a feat to be bested in the humanistic warmth department by David Cronenberg.”

Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir: “I see Amour less as a tale of suffering and death—although some of it is admittedly difficult to watch—than as one about the dignity and nobility of human life even in the face of those things.”

Mary Corliss in Time: “Often playing passive roles, Trintignant here is a man who quietly takes charge of his wife’s siege; he whispers no love sonnets but is a man heroically devoted, determined to do justice to the final act of a long affair. Riva, in the 53-year journey from Hiroshima mon amour to Amour, has lost none of her startling commitment to the craft. Like actresses who play the flinty heroines of Samuel Beckett’s late plays, Riva must convey Anne’s personality through severely limited means: the slouch or starch in her body, the clarity or opacity in her eyes. Riva’s channeling of a woman who has lost memory and emotion—lost what some would call her soul—is a thrilling, draining emotional insight.”

More from Kathleen Murphy (MSN Movies, 5/5), John Oursler (Cinespect), and Kenneth Turan (Los Angeles Times). Aaron Hillis interviews Haneke for Indiewire, and Mindy Farabee talks with Riva for the LAT.

Update, 12/26: “I’ve never dreaded anything I looked forward to as much as Amour,” writes Elina Mishuris in the L.

Updates, 12/29: For the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane, “what makes Amour so strong and clear is that it allows Haneke to anatomize his own severity. Anne, for example, used to teach piano, and, for a few tender seconds, we see her play Schubert in Georges’s imagination. Then we think of The Piano Teacher (2001), in which Haneke’s heroine was led by a musical rapport into a lethal amour fou. Does the new film redeem such horror, or is all beauty fated to be ominous and frail?”

Aysegul Sert interviews Isabelle Huppert for Salon.

Update, 1/5: “Haneke stays (with a few signal and fake exceptions) resolutely outside [Georges and Anne’s] minds,” writes the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody, “filming the exterior details of their lives with a repressed, even a constipated style—mainly static frames from a reserved middle distance, holding in emotion as well as information, keeping from viewers what he knows about the characters and what the characters know about themselves. This retentive realism is a dominant mode of so-called art-house filming; it characterizes such movies as Christian Petzold‘s Barbara, Cristi Puiu‘s Aurora, Nuri Bilge Ceylan‘s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, and many other recently acclaimed movies. And it is as much a style of script and of narrative construction as of image-making. It doesn’t always have the same implications; in Barbara, it’s a mere elegance that dresses a potboiling story in the austere and streamlined chic fashions of a gentrified cinema; in Aurora, it represents political and sociological intentions. In Haneke’s film, the style is the premise for the setup: the willful exclusion of the characters’ inner life (yes, there is a dream sequence and a brief fantasy—both generic) throws the burden of interpretation on viewers. It’s Haneke’s usual strategy: to make viewers complicit with morally dubious deeds while keeping his own hands resolutely clean.”

Updates, 1/9: Writing for the New York Review of Books, Francine Prose finds Amour to be “far scarier and more disturbing than Hitchcock’s Psycho, Kubrick’s The Shining, or Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, and like those films, it stays with you long after you might have chosen to forget it. Like all of Haneke’s work, Amour raises interesting and perhaps unanswerable questions: Can a film be a masterpiece and still make you want to warn people not to see it?”

Teju Cole for the New Yorker: “‘When we look at the image of our own future provided by the old we do not believe it: an absurd inner voice whispers that that will never happen to us—when that happens it will no longer be ourselves that it happens to.’ Thus did Simone de Beauvoir’s The Coming of Age address the fundamental disbelief with which we regard old age. It is something that happens, that is certain, but it only happens to other people. In Amour, Haneke shows us that this disbelief remains even for those who are no longer young. One is intact to oneself, and the certainty of one’s radical diminishment is hard to credit.”

Update, 1/10: Anna Tatarska interviews Oscar nominee Emmanuelle Riva here in Keyframe.

Update, 1/12: Amour has opened in Chicago, and in Time Out, A.A. Dowd calls it “the most brutally honest picture ever made about growing old and wasting away.” 5 out of 5 stars. In the Sun-Times, Roger Ebert, recalling the opening scene, wonders, “What alchemy drew my eyes to one particular old couple in the audience? A director can stage a shot to force us how to look at it, but Haneke here is deliberately objective. Still, I noticed these two.” J.R. Jones in the Reader: “Anger, humiliation, and despair all take their toll, but Riva, extraordinary in the role, also communicates the class, intelligence, and beauty that the husband still sees.”

Update, 1/18: “If you’re someone who has dealt with the reality of a dying parent or spouse, Amour may seem both tough sledding and blessedly free of piety,” writes the Boston Globe‘s