The first round of reviews comes from the trades, so the emphasis is, of course, on Paramount’s $130 million gamble. Skimming over most of the risk assessment, we begin with Variety‘s Scott Foundas: “Having made movies about obsessive characters looking for God—or something like Him—in the numerology of the Kabbalah (Pi), at the end of a heroin needle (Requiem for a Dream), and in the outer reaches of the galaxy (The Fountain), surely it was only a matter of time before Darren Aronofsky got to making one about a man with a direct line to the Creator. And so we have Noah, in which the world’s most famous shipwright becomes neither the Marvel-sized savior suggested by the posters nor the ‘environmentalist wacko’ prophesied by some test-screening Cassandras, but rather a humble servant driven to the edge of madness in his effort to do the Lord’s bidding.” This bit here is especially nice: “Once upon a time, the famously austere French director Robert Bresson was enlisted by Dino De Laurentiis to film the Noah story for his planned The Bible … In the Beginning, only to be fired when he told the producer he didn’t intend to film any of the animals, just their tracks upon the sand. And there may be no better description of Aronofsky’s film than to say that it has one foot in the world of Bresson and the other in that of Jerry Bruckheimer.”

“Already banned in some Middle Eastern countries, Noah will rile some for the complete omission of the name ‘God’ from the dialogue, others for its numerous dramatic fabrications and still more for its heavy-handed ecological doomsday messages, which unmistakably mark it as a product of its time,” writes Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “One of the striking things about the Noah tale is that it presents a fallible Creator, one who admits to disappointments over shortcomings in the product of the sixth day of creation with the remark, ‘I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the ground, man and beast and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.’ The exceptions are middle-aged Noah (Russell Crowe), his wife, Naameh (Jennifer Connelly), and sons Shem (Douglas Booth), Ham (Logan Lerman) and Japheth (Leo Carroll), who are estranged from the rest of humanity and live apart from it, struggling to survive in forbidding surroundings. Noah’s physical and mental toughness is strengthened by an abiding faith, and Crowe’s splendidly grounded work here recalls some of his finest earlier performances, notably in Gladiator, The Insider and Cinderella Man, in which he embodied values of tenacity, trustworthiness and resourcefulness that inspired confidence that his characters would do the right thing.”

Back in February, Steven D. Greydanus, currently studying to be a Catholic deacon, urged readers of the National Catholic Register to approach Noah with an open mind. His piece earned him a few tweets from Aronofsky and Crowe—and an interview with the director. In today’s review, he calls Noah “a work of art and imagination that makes this most familiar of tales strange and new: at times illuminating the text, at times stretching it to the breaking point, at times inviting cross-examination and critique…. For a lifelong Bible geek and lover of movie-making and storytelling like me, Noah is a rare gift: a blend of epic spectacle, startling character drama and creative reworking of Scripture and other ancient Jewish and rabbinic writings. It’s a movie with much to look at, much to think about and much to feel; a movie to argue about and argue with.”

Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn finds that Aronofsky’s “murky, ill-conceived take on the world’s oldest disaster story contains some of the most pristine visuals produced on a mass studio scale in some time. But it’s also constantly tethered to a dull, melodramatic series of events out of whack with any traditional interpretation of the material. By turning the monolithic odyssey into a sword-and-sandals showdown with occasionally cosmic tangents, the 137-minute studio venture contains the glimmers of a truly visionary achievement flooded by half-baked ideas.”

“Working with long-time collaborators cinematographer Matthew Libatique and composer Clint Mansell, Aronofsky has envisioned Noah’s world to be a bleak, unforgiving landscape decimated by humanity’s depravity in the wake of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace,” writes Tim Grierson in Screen. “The director is occasionally able to make that bleakness resonant—Noah at times exudes the sickening dread of a post-apocalyptic drama—but more often than not, this is a familiar cinematic portrait of societal collapse…. The movie wants to be a love story, a family drama, a war movie and a disaster film, but the different tones and genres aren’t properly integrated.”

For TheWrap‘s Alonso Duralde, “Noah has its share of interesting ideas, from rock-covered fallen angels to Noah’s idea that he and his family should be the last human beings on earth, per his interpretation of what ‘the creator’ tells him, but the film winds up feeling like a bit of a soggy slog, both overblown and underwritten.”

Nathan Adams at Film School Rejects: “The Upside: Dark, complex, intense; basically just the sort of thing you’ve come to expect from Aronofsky. The Downside: Bleak, divisive, will likely go too far for many; basically just the sort of thing you’ve come to expect from Aronofsky.”

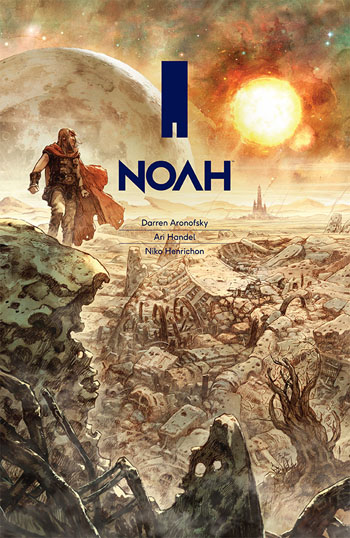

For Paste, Mark Rozeman reviews the graphic novel written by Aronofsky and Ari Handel and drawn by Niko Henrichon: “Released by Image Comics, Noah presents a lush translation of Genesis 5:32-10:1 that melds the realism of The Wrestler with the surreal imagery of The Fountain.” Rob Bricken talks with Aronofsky about the book for io9.

New York’s Museum of the Moving Image launches a Darren Aronofsky series today, culminating with a preview screening of Noah on March 27. At Moving Image Source, Adam Nayman surveys the career: “Aronofsky was not the first termite who dreamed of being an elephant: in with The Fountain, the director was merely treading—and tripping—where predecessors like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg had all gone before. But where his own showbiz kid contemporaries, from Jonze and Sofia Coppola to Christoper Nolan to both Andersons all debuted with (comparatively) modest movies, Aronofsky’s cinema hinted towards the grandiose from the very beginning. Produced on a shoestring but as tightly wound as a Gordian knot, Pi (1998) was about nothing less than an underdog genius who believes he’s got the secrets of the Universe at his fingertips—a portrait of the artist as a young man, perhaps.”

Updates, 3/29: In the New Republic, Brook Wilensky-Lanford argues that “all the religious hubbub over Darren Aronofsky’s Noah—the National Religious Broadcasters getting the studio to add a disclaimer, the ban in several Gulf nations, the claim that the director ‘superimposed’ an ‘anti-Christian’ message—is just predictable political posturing…. Impressively, Aronofsky’s interpretation manages to stay ‘true’ both to the messiness of the Old Testament and to his own directorial sensibilities.”

Writing for Rolling Stone, Nick Schager argues that “Aronofsky’s output is actually deeply religious, be it via overt quests for (and questions about) God, or through allegorical inquiries into issues of atonement and redemption…. After taking a look through Aronofsky’s back catalog, you start to realize: If there’s any modern moviemaker fit to direct an Old Testament tale of wrath and redemption, it’s him.”

More reviews: Bryan Abrams (The Credits), Melissa Anderson (Artforum), Nicholas Bell (Ioncinema, 2/5), David Edelstein (New York), Eric Ortiz Garcia (Twitch), Eric Henderson (Slant, 2/4), Robert Horton (Herald), Richard Lawson (Vanity Fair), Andrew O’Hehir (Salon), Keith Phipps (Dissolve, 3.5/5), James Rocchi (Film.com, 4/10), A.O. Scott (New York Times), Matt Zoller Seitz (RogerEbert.com, 3/4), Choire Sicha (Awl) and Anne Thompson.

Updates, 4/3: Writing for Forward, Jay Michaelson explains why he believes that Aronofsky is “absolutely in accord with Jewish traditions, and absolutely opposed to Christian ones…. Noah, then, is a film that fundamentalist Christians are right to abhor. It is midrashic, magical, and radical. Its characters are deeply flawed and deeply complicated. It questions the meaning of faith. It is, in the best senses of the word, quintessentially Jewish.”

“Is there any ideology in the mishmash?” asks Caleb Crain, writing for the Paris Review. “The flavoring of the movie is from a venerable populist recipe: push radicalism to a discrediting extreme, then pull the viewer back, with sentiment, to the comfortable middle-of-the-roadism that he began with.”

But in the Financial Times, Nigel Andrews asks, “Why is Aronofsky’s film wonderful? Because his revisions and embellishments add heat—Homeric, at times hubristic—to a story made tepid by centuries of Sunday Schooling.”

The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw grants that “this roaring fantasy action adventure is a world away from childhood pieties. Yet it’s done away with some of the beauty, clarity and simplicity. Something has been lost in the storm.”

Update, 4/7: “The fact that Darren Aronofsky’s Noah is played by Russell Crowe might initially have caused some anticipatory titters,” writes Jonathan Romney for Sight & Sound, “but actually proves to be one of the approachable and highly effective elements which makes the film work. Crowe’s presence as a muscular, tormented struggler, an antediluvian working stiff, gives Noah a human, even earthbound grounding that allows its considerable strangeness and ambition to take flight; makes it epic in the properly transcendental sense that DeMille would have recognized.”

Update, 4/9: Via Sam Adams at Criticwire:

Update, 4/10: For the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody, “the adolescent spark behind Noah, (which Tad Friend discusses in his Profile of Aronofsky in the magazine), far from being an obstacle or a pitfall, is central to its virtues. The movie grows from a sense of wonder inspired by the contemplation of Biblical grandeur, the recognition that there was a world in which divine and human things seemed to be integrated…. The power of Noah arises from Aronofsky’s shuddering comprehension that the person who thinks he’s in touch with God is capable of anything. The movie stands on its head the Dostoyevskian dictum ‘If God does not exist, everything is permitted.'”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.