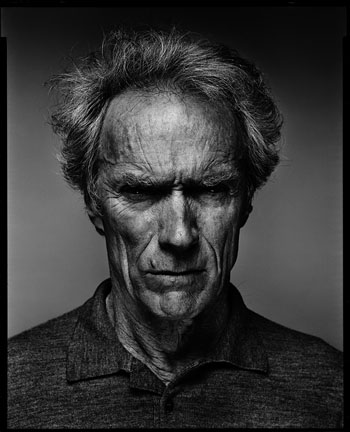

A very happy birthday to Clint Eastwood, born on May 31, 1930 in San Francisco. To celebrate, Time has posted an gallery of pictures and posters annotated by the late Richard Corliss and Eliza Berman. There are around 20 entries in all, and here’s the first, on Revenge of the Creature (1955):

“Doc, could you come here a minute?” was Eastwood’s first line in his only scene in Jack Arnold‘s sequel to the B-minus horror hit Creature from the Black Lagoon, as a lab assistant to star John Agar. A 23-year-old signed by Universal, Eastwood got nowhere playing bit parts: a jet pilot ordering a napalm drop on a giant spider in Arnold’s Tarantula, a sailor buddy of Donald O’Connor and his talking mule in Francis in the Navy. None brought him acclaim, or even notice, until much later. On a 1997 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, Crow T. Robot watches Clint’s Revenge of the Creature performance and opines, “This guy’s bad. This is his first and last movie.”

And of course, there’s hardly anyone on the planet who won’t get the joke. The IMDb lists nearly 70 credits as an actor, and nearly 40 as a director. “His persona as a laconic anti-establishment icon was cemented early in his career, through his starring roles in A Fistful of Dollars (Sergio Leone, 1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good the Bad and the Ugly (1966),” wrote Deborah Allison for Senses of Cinema in 2003.

Andrew Tudor for Film Reference: “Simple variations upon the Man with No Name have served well in the likes of Hang ’em High, Two Mules for Sister Sara, Joe Kidd, High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. A modern urban counterpart turned up in Coogan’s Bluff in the guise of a policeman from out West blundering none too appealingly through New York, and emerged fully fledged in another film made for Don Siegel, the controversial and highly successful Dirty Harry. Its central character, Harry Callahan, an obsessive, ruthless, and violent cop, became even more ruthlessly violent in its immediate sequels, Magnum Force and The Enforcer, rapidly joining the Man with No Name as a permanent fixture in the modern cinema’s chamber of action heroes.”

“Early on, his outsider heroes operated with an unshakable sense of right,” wrote David Denby in the New Yorker in 2010. “Such men were angry enforcers of order defined not by law but by primal notions of justice and revenge. ‘Nothing wrong with shooting as long as the right people get shot,’ Eastwood’s Dirty Harry said in Magnum Force (1973). Removed from normal social existence, these low-tech terminators eliminated ‘the right people’ and withdrew into bitter isolation again. Noblesse oblige—or, perhaps, vigilante oblige. Yet by mid-career, in the late 1970s and early 80s, even as films in the Dirty Harry series were still coming out, Eastwood began showing signs of regret, twinges of doubt and self-reproof, along with a broadening of interest and a stunning increase of aesthetic ambition.”

Deborah Allison: “Eastwood started directing just a few years after making his name as a movie star, although his presence as an actor in the majority of these early projects tended to eclipse his directorial achievements. Nevertheless, by the mid-1970s he was already starting to be recognized as a talented director with a consistent and idiosyncratic style. This critical recognition was enhanced by his movement away from genre pictures, as he showed instead an increasing predilection for less commercial projects such as Bird (1988) and White Hunter, Black Heart (1990). His position as one of America’s most respected directors was cemented by his receipt of an Oscar for directing Unforgiven (1992).”

David Denby: “He made comedies, bio-pics, and literary adaptations (and twice starred with an orangutan). The movies shifted from stiff, stark, enraged fables, decisive to the point of patness, to something more relaxed and ruminative and questioning. In Unforgiven, he holds scenes a few extra beats, so that characters can extend their legs, scratch behind their ears, air some issue of violence or honor. The movie comments on itself as it goes along.”

“High Plains Drifter is a remarkable film,” wrote Fernando F. Croce for Slant in 2007. “Eastwood’s sophomore directorial effort, it is also the first western he directed; Leone’s influence is obvious in its baroque excesses, but Eastwood’s aim is not to pay homage to the genre but to usher in its apocalypse.”

Profiling Eastwood for Variety last summer on the occasion of the release of Jersey Boys and American Sniper within months of each other, Scott Foundas listed a few “truisms of making a movie with Eastwood: He typically does no more than two takes of any given shot—sometimes even shooting, then using, what actors think is a mere rehearsal; he works with the same crew time and again; is usually ahead of schedule and under budget; call time is rarely before sunrise; and everyone gets home by dinner.”

When Foundas interviewed Eastwood for the LA Weekly in 2008 (Gran Torino was the movie of the moment), he noted that in “the latter half of Eastwood’s filmmaking career…, images of violence have rarely been offered up for mere titillation or visceral excitement. He points to the scene in the Oscar-winning Unforgiven in which the retired gunslinger William Munny (played by Eastwood) and his former partner Ned (Morgan Freeman) gun down a young man with a bounty on his head, who has violently assaulted a frontier-town prostitute. ‘Afterward, there’s that little moment of, “Jesus, I didn’t want to ever do this again,”‘ Eastwood says.”

“When I retire,” Eastwood told Roger Ebert in 1986, “I want to be able to think in terms of a broad spectrum of roles. I’d hate to be the guy who made 35 Westerns and 15 cop pictures. I’d want to know what they were about. How interesting were the characters? Even with Dirty Harry, we tried to stretch the character. When I made Tightrope, I didn’t play a fantasy cop, a superman—but more or less just a good detective who was haunted by his inner self.”

In 2012, Ebert kicked up a flurry on Twitter when, responding to Eastwood’s ad-libbed performance at the Republican National Convention (you may remember that he addressed an empty chair, implicitly asking us to imagine that President Obama was sitting on it), Ebert tweeted: “Clint, my hero, is coming across as sad and pathetic.” A few days later, Ebert emphasized, “Let me be clear: I love this man. I don’t give a damn what his politics are. For me it was the same with John Wayne.” Eastwood, he argued, had been thrown off by the Republican talking points he’d been asked to work into his routine.

I suspect that the incident might never have occurred in the first place if an ad Eastwood made for Chrysler that aired during the Super Bowl in early 2012 hadn’t been read far and wide as an endorsement for a second Obama term. It must have riled him up, but it’s difficult to imagine anyone reading the script at the time and not recognizing that it was laying out the argument, practically line for line, that Obama’s reelection team would be making throughout 2012:

Well, out of the frying pan… From Wikipedia: “As of May 27, 2015, American Sniper had grossed $349.9 million in North America and $193.4 million in other territories for a worldwide total of $543.3 million, against a budget of around $58 million. Calculating in all expenses and revenues, Deadline.com estimated that the film made a profit of $243 million, making it the second most profitable film of 2014 only behind Paramount’s Transformers: Age of Extinction. Worldwide, it is the highest-grossing war film of all time (breaking Saving Private Ryan‘s record) and Eastwood’s highest-grossing film to date. It is the seventh R-rated film to gross over $500 million.”

Some find the remarkable popularity of American Sniper even more troubling than the film itself. In “The Trouble with Clint,” an overview of the career as seen through the lens of American Sniper’s opening scene, Jacob Krell wrote last month for the Los Angeles Review of Books, “What Eastwood is after now is, in a word, simplicity, though what ‘simple’ means in this case is a bit more complicated, and more destructive, than simplicity tends to be. For when this aesthetics of simplicity takes on a political valence, it ends up being far more insidious, and far more appealing, than a jumbled conversation with an empty chair seems to indicate.”

“As for his follow-up to American Sniper,” Variety‘s Brent Lang and Dave McNary reported last month from CinemaCon, “Eastwood denied recent speculation that he would direct a film about Richard Jewell, the security guard who discovered a suspicious backpack in the Olympics compound during the 1996 Games in Atlanta. He said it wasn’t clear if the film would come to fruition.” Whatever his next project might be, we can be sure that the sensibilities of neither liberals nor conservatives will factor into Clint Eastwood’s decision to make it.

Update, 6/2: And now, we know. From Deadline‘s Anita Busch: “Clint Eastwood will helm Warner Bros. Pictures’ as-yet-untitled drama about the life of Captain Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger, who became an American hero when, in 2009, he landed his disabled jet on the Hudson River, saving the lives of everyone aboard—passenger and crew, which numbered 155 people.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.