Chinese Realities/Documentary Visions, opening on Wednesday at MoMA and running through June 1, “aims to reflect the evolution of documentary practice in China over the past 25 years, revealing the growth and ever-increasing influence of nonfiction film and media. The selections, encompassing a wide expanse of Chinese film and media, including state-approved productions, underground amateur videos, and Web-based Conceptual art, provide a vivid look into a society in perpetual transformation.”

“The filmmakers whose work is on display alternately belong to what has been labeled the Sixth Generation, the Urban Generation, the Tibetan New Wave, and the post-Sixth Generation Independent Documentary movement,” writes Jason Fox in the new Brooklyn Rail. “The multiple banners speak to the difficulties of categorically defining a geographically diverse and rapidly evolving group of practitioners, but they also belie the monumental importance of the work on display as a unified movement in global cinema. As the films on screen attempt to keep pace with the ways that Chinese localities are being shaped by and against the forces of neoliberalism, they propose radical new approaches to documentary cinematography and cinematic realisms, aesthetically gratifying feature-length (and longer) work on low-to-no budget, and productive modes of resistance to an antiquated state-sponsored studio film system.”

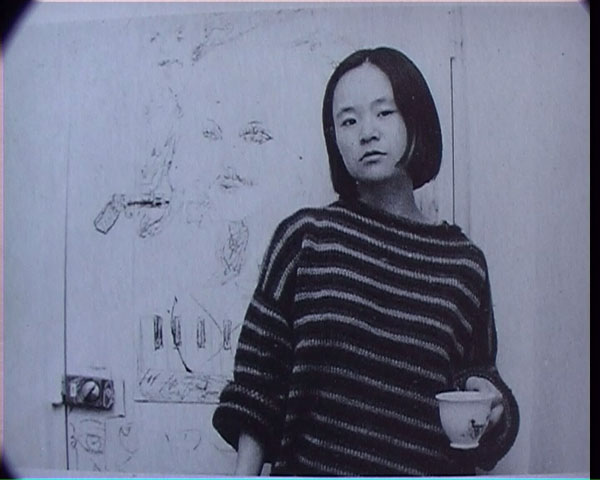

What follows are capsule previews of Li Hong’s Out of Phoenix Bridge (1997), “a remarkably intimate and incisive documentary portrait of female migrant workers living in Beijing,” Zhang Yimou’s The Story of Qiu Ju (1992), “a street-level work of critical realism shot in a quasi-documentary mode,” Wang Bing’s “masterful long-form” West of the Tracks (2003), Wu Wenguang’s Fuck Cinema (2005), “a cynical reflection on the dissonance between the fantasies and pursuit of pleasure that the Chinese mass media engenders in many of its consumers,” Cao Fei’s short i.Mirror (2007), comprised of footage from Second Life, Huang Weikai’s Disorder (2009), “a revisionist city symphony compiled of footage collected from 12 different amateur videographers,” Pema Tseden’s Old Dog (2011), “a quietly devastating work of Tibetan New Wave Cinema,” and Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II (2009), which “applies a rigorous cinematic formalism to an intimate family gathering.”

The series of 28 films has been curated by MoMA’s Sally Berger and our own Kevin B. Lee, Vice President, Programming and Education, at dGenerate Films, where, every day this month, you’ll find a primer on one of the entries. Posted so far are descriptions and reviews of Xia Jun’s River Elegy (1988), Wu Wenguang’s Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers (1990), Zhang Yuan’s Mama (1990), the previously mentioned Fuck Cinema, and the China Villagers Documentary Project (2005).

Updates, 5/8: “Given the content of the films in the MoMA series,” writes Anthony Kaufman at Sundance Now, “it’s easy to see the [New Documentary Movement] within the context of China’s recent and singularly seismic shifts, from Communist-era industrialization to a 21st century global capitalism on steroids. Furthermore it’s tempting to suggest that these films express a hunger for more truthful depictions of reality in contrast to state sanctioned cover-ups and propaganda, particularly in the years leading up to and after Tiananmen Square. But according to scholars of the NDM, complex institutional factors have also led to a shift towards independent, socially aware filmmaking—factors such as the decentralization and deregulation of the TV industry as well as an increase in media outlets. With this lurching forward into the techno-consumerist age, a greater space has opened up for critique and reexamination. This extends to both the films’ differing approaches to ‘reality’ as well as to what these changes have wrought upon their subjects, the once industrious citizens of Mao’s China who are now unemployed, alienated and disenfranchised.”

The latest primers, with excerpts from reviews and more, up at dGenerate Films: Zou Xueping’s The Satiated Village (2011), “for which Zou interviewed residents of his hometown about their experiences during a famine that killed tens of millions,” and The Story of Qiu Ju.

Updates, 5/11: The latest primers at dGenerate: Jiang Yue’s The Other Bank (1994), “a penetrating reflection on the transformative effects of art (both theater and documentary film), and a portrait of a generation’s quest to find fulfillment in 1990s China,” and Duan Jinchuan’s No. 16 Barkhor South Street (1996), depicting “with extraordinary vividness, the everyday workings of a government committee that serves a neighborhood in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital”; plus i.Mirror and Out of Phoenix Bridge.

Updates, 5/16: First off, Kevin B. Lee introduces the video we’ve posted here in Keyframe today, noting that he produced one for MoMA “introducing some of the films and major themes of the series. It turned out that the films yielded much more than one short video could contain, so I’ve made an additional video essay further exploring how these films engage with China’s constantly transforming reality, and in doing so transform it even further.”

Moving Image Source has posted an extensive survey of the series by Aaron Cutler, who begins with Bumming in Beijing, “the film that would come to be widely known as China’s first independent documentary…. Wu interviews five young fellow freelance artists who have chosen to abandon their government-assigned life paths to pursue their crafts in the nation’s artistic capital. A theater director speaks for the group when he says that pursuing what he enjoys was the only realistic alternative to killing himself or living like an aimless conformist. They do this despite knowing that a strict government can upend their homes and lives at any time.”

At Twitch, Christopher Bourne reviews six films in the series, beginning with Mama, which “began its life as something very different than what it eventually ended up to be. This project began as a screenplay for a children’s film entitled The Sun Tree by lead actress Qin Yan, based on her own experiences and inspired by a story by the writer Dai Qing; Yuan, a senior at the Beijing Film Academy at the time, was slated to be the film’s cinematographer. After a series of circumstances, including two state film studios rejecting the project, and the association with the writer Dai Qing being problematic because of his support for the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations, Zhang and his collaborators radically reworked the screenplay to more closely reflect the actual lives of people in Chinese society at that time. The resulting film was shot on a shoestring budget of about $1300, largely in Zhang’s own apartment…. The result is a hybrid film in which fiction and reality intertwine to create a powerful, and artful, portrait that transcends the typical ‘social problem’ movie.”

J. Hoberman at Artinfo: “Old Dog, which essentially documents the disappearance of traditional Tibetan culture, is premised on the current market in Tibetan mastiffs; nouveau riche Chinese dog fanciers are evidently willing to pay a small fortune for the ‘exotic’ mastiffs used by Tibetan sheep-herders. Tseden, who was named one of the 50 Best Filmmakers Under 50, last year by Cinema Scope, is himself the child of nomadic herders…. Austerely pictorial, shot with the generally static camera characteristic of Chinese documentary, Old Dog has a powerful sense of place.” It’s “subtle and affecting filmmaking.” For more on Old Dog, see Critics Round Up.

At In Review Online, Kenji Fujishima especially recommends Disorder, “among the most formally innovative and visionary works of cinematic non-fiction to come along in recent years. Somewhat like Leviathan, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel’s astonishing fishing-boat documentary earlier this year, Disorder is culled entirely from footage taken from the ground—but whereas the cameras in Leviathan were attached to creatures and objects, Huang’s footage comes from amateur videographers (in other words, Huang beat Kevin MacDonald and his amateur-video assemblage Life in a Day by a good two years). Whatever the sources, however, both of these films exude the sensibilities of true artists, shaping existing footage into a distinctive, coherent, personal vision.”

Cole Hutchison at Cinespect: “The tears streaming down the face of one 16-year-old girl in Railroad of Hope, as she stands in line for the third day straight to hopefully board a train which will deliver her to the education that will enable her to become a police officer so that she can ‘serve the people,’ are devastatingly representative of a great paradox: A citizen so model and naïve to construct her dreams around an indoctrinated slogan is still entirely dependent upon a callous toss of the cosmic dice in a society where luck never seems to be on the side of the common man or woman.”

For the Wall Street Journal, Steve Dollar talks with Kevin and Sally Berger.

Update, 5/20: Yumen “is exactly what MoMA’s rubric promises,” writes J. Hoberman at Artinfo, “an art-doc depiction of despoliation that’s almost Lynchian in its casual weirdness.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.