When Post Tenebras Lux premiered at Cannes last year, Carlos Reygadas won the festival’s best director award and reviews that ranged from awe through bafflement to angry derision. Tomorrow, the film begins a two-week run at New York’s Film Forum, and Dennis Lim profiles Reygadas for the New York Times: “Whether serving up bloodshed and deeply unerotic sex in transgressive melodramas like Japón (2002) and Battle in Heaven (2005) or contemplating the enigmas of faith and love in the Mennonite adultery drama Silent Light (2007), his films are invariably primed to stir debate: the shock of the new or the emperor’s new clothes?… Michel Lipkes, a Mexican filmmaker and programmer who has a cameo in Post Tenebras Lux, said in an e-mail that Mr. Reygadas’s work both embodies and critiques Mexican culture. The films often acknowledge the country’s ‘baroque values’ and ‘surreal qualities,’ Mr. Lipkes said. ‘But Mexico is also a generally moralistic culture, so his attitude toward this mentality is to question it, defy it.’ While Mexican cinema’s big three—Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro, known collectively as the Three Amigos—have plotted a path to crossover success, Mr. Reygadas’s confrontational, low-budget films have paved the way for independent voices like Amat Escalante and Nicolás Pereda. ‘He radicalized the cinematographic possibilities of Mexican culture,’ Mr. Lipkes said.”

“Ostensibly the story of a brusque and brutish family man named Juan (first-time actor Adolfo Jiménez Castro) who relocates his beautiful young wife and their two small children to a mini-mansion in the Mexican countryside,” writes David Ehrlich at Film.com, “Post Tenebras Lux—a Calvinistic expression of salvation that translates from the latin as ‘after darkness, light’—is ultimately a rather simple portrait of self-reflection, a fevered journey into the dark heart of a male’s moral universe.”

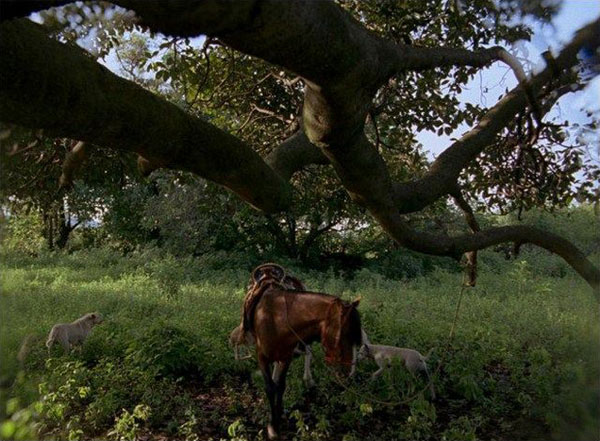

And J. Hoberman, writing for Artinfo, is not a fan. “[I]t begins with the director’s young daughter toddling through a soggy field somewhere in rural Mexico naming what Stan Brakhage, whose films provide a precedent for this focus-deranged footage, might call the Animals of Eden: ‘Vacas! Caballos!’ Rumble of distant thunder…. It’s a splendid curtain raiser for an intermittently brilliant, but more often baffling and ultimately insipid film…. No less than Lars von Trier or Terrence Malick, Reygadas is an admirer of Andrei Tarkovsky (in this case The Mirror) but if Malick sentimentalizes the Russian master’s lyrical pantheism, Reygadas, even more than von Trier, ambivalently travesties Tarkovsky’s at times overweening spirituality.”

After that opening sequence, comes “Satan, a neon-red, horse-hung sartyr who enters a home, toolbox in hand, and retires to a bedroom, though not before exchanging glances with a seemingly unfazed boy who stands in an adjacent room,” writes Slant‘s Ed Gonzalez. “This mesmerizing appearance by an animated devil is at first confounding, though not exactly out of place in a film where moments small and grand, from a child jumping half-naked on his parent’s bed to the felling of trees, exude an almost Biblical gravity. That the devil lurks inside man, and that evil seems to come as naturally to the idle rich as it does to the back-breaking poor, is just one key that unlocks Post Tenebras Lux, an at once dazzling collage of willfully obfuscatory imagery and philosophizing that’s most interesting as a window into Reygadas’s sense of the marginalization that his own privilege affects.”

For Tony Pipolo, writing for Artforum, “while Silent Light unfolds in an exclusive social community marked by a near-extinct language, Post Tenebras Lux carries the imprint of an increasingly fracturing, indomitable capitalist culture. This is directly reflected in the film’s structure, in which the narrative tracing the fortunes of an upscale Mexican family is frequently broken and displaced by characters and events with only peripheral connections to the primary ones…. Reygadas’s taste in mentors is exemplary. If Carl Dreyer‘s Ordet (1955) was the unacknowledged inspiration behind Silent Light, Bresson’s The Devil, Probably (1977) seems to have been on Reygadas’s mind here, as a later scene of trees falling in a forest also suggests. To boot, Bresson’s narrative also splits its focus between the suicidal trajectory of its main character and the indictment of a world bent on destroying its natural resources while offering pathetic cultural compensations…. As he has with every film he’s made thus far, Reygadas gives us contradictory views that echo the mysteries of human existence.”

Updates, 5/2: “Part of what impressed me about Silent Light was my sense that Reygadas had not only been influenced by my own favorite films, but that he had seen those films in the same way and admired them for the same reasons that I had,” writes Francine Prose for the New York Review of Books. “In Post Tenebras Lux, if we are hoping for the coherent narrative that drew us through Silent Light, we must instead settle for a montage of scenes that appear to have been assembled in an order understood best—and perhaps only—by the director.” She hopes that “Reygadas will, in the future, redirect his attention away from the work of his cinematic heroes and his own memories and feelings—and return to the lives of others, and to the endlessly interesting faces and stories around him.”

“Silent Light was notable for its majestic widescreen compositions,” writes Mike D’Angelo at the AV Club. “Post Tenebras Lux, by extreme contrast, was shot in the nearly square Academy ratio, and all exteriors employ a strange effect in which the frame is sharp at the center but goes blurry in a circle around the edges, with multiple exposures occurring across the border area. The purpose of this device is unclear… The film is never less than fascinating, but it appears to be so intensely personal as to be all but indecipherable to viewers not personally acquainted with the filmmaker, or at least in possession of the press kit.”

For the NYT‘s Manohla Dargis, “while Mr. Reygadas doesn’t always make it easy to watch his work (occasionally the reverse), the Carlos Reygadas Experience is always a worthwhile trip. And head-tripping is very much part of Mr. Reygadas’s cinema, whether or not he’s tethered his sometimes lovely, sometimes appalling visions to a strong narrative.”

For Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir, Post Tenebras Lux “might be the movie of the year–if we lived in some other universe where people didn’t expect movies to ‘make sense,’ or even to tell a story in the normal sense. In this universe, Reygadas is often understood as a provocateur, not without reason. His first feature, Japón (not set in Japan) featured documentary-style scenes of cruelty to animals that outraged some viewers, and his 2005 Battle in Heaven featured several scenes of unsimulated sex, including a memorable blow-job sequence that opens the film. His most recent film, Silent Light, was the first and no doubt only feature ever made in the Plautdietsch language, a form of Low German spoken by the Mennonites of northern Mexico, and depicted a miraculous event made flesh. While Post Tenebras Lux… makes little effort to please the audience or explain itself, I never felt Reygadas was trying to be confrontational for its own sake.” Indeed, “if you’re open to an abstract, associative experience that’s completely different from most other movies (or all of them), this modestly scaled and deeply personal film is a work of visionary daring, beauty and heartache.”

More from Brian Clark (Twitch), Steve Erickson (Voice), Tom Hall (Filmmaker), Eric Kohn (Indiewire), Nicholas Rapold (L), and Keith Uhlich (Time Out New York, 4/5).

David Barker talks with Reygadas for Filmmaker, where you’ll also find a set of screenplay extracts and a few storyboards.

Update, 5/6: “The ecstatic cinematic rhapsody that is Post Tenebras Lux is not for everybody—but noting this is not to suggest that it couldn’t be.” Jeff Reichert in Reverse Shot: “Though it scans like an impenetrable extended anti-narrative of non sequiturs peppered with visual tics and odd happenings, it’s also somehow the most human and approachable film Mexican filmmaker Carlos Reygadas has yet made.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.