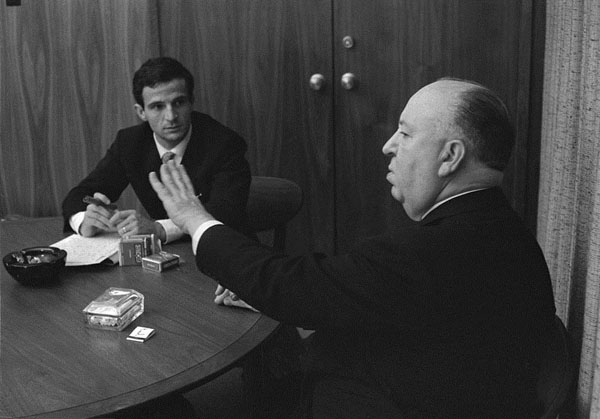

“The marathon 1962 interview of Alfred Hitchcock by François Truffaut that became one of the seminal books on filmmaking itself becomes the subject of a film in Hitchcock/Truffaut,” begins Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “Something of a film buff’s nirvana not only because of its two participants but due to the onscreen presence of David Fincher, Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson and other directorial luminaries talking about them, Kent Jones’s latest look at an eminent creative figure has the air of a bunch of extreme film buffs sitting around talking in depth on a subject about which they’re almost alarmingly obsessive, but that’s a big part of the fun.”

The doc “doesn’t offer much more than the experience of watching smart people talk concisely about art, but it does it very well,” writes Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club. “First published in 1966, Hitchcock—popularly known as Hitchcock/Truffaut—is a book-length conversation between Alfred Hitchcock and critic-turned-director François Truffaut, covering the former’s entire filmography in chronological order. It’s one of those indispensables that anyone with a passing interest in movies should own. Jones’s film is similarly pitched at entry-level viewers, laying out ideas about film and filmmaking with admirable clarity.”

“Rather in the spirit of the original interview, the emphasis is on Hitchcock’s work, rather than Truffaut’s, but the master’s work is seen through the lens of Truffaut, whose brilliance as a critic shines through,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “Jones’s film takes us through what their childhoods had in common: a terrifying experience in prison. Truffaut was looking for a father figure—he found one in the great André Bazin of Cahiers du Cinéma (perhaps Hitchcock was closer to being an inspirational teacher than a father)—but it was Hitchcock who freed Truffaut and whom Truffaut, in turn, wanted to free from his reputation as a mere showman…. Do we have the overwhelming sense of groundbreaking cinephile excitement that made the Hitchcock/Truffaut interview possible? I wonder. A fascinating film.”

“For 50 years, these conversations have existed in book form. Jones has set them free, juxtaposing the audio recordings with relevant scenes from the films,” writes Stuart Jeffries in a terrific piece for the Guardian laced with quotes from Jones. “Hitchcock clearly revels in disclosing some of his secrets. As we watch the superbly sinister scene in the 1941 thriller Suspicion in which Cary Grant slowly, but implacably, ascends a spiral staircase towards Joan Fontaine’s bedroom, we may well wonder why the glass of milk he’s carrying looks so ominous and hyperreal. Because, Hitchcock explains, he lit it from inside with a little lightbulb. Truffaut gasps.”

In the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan reports that “when Jones, who’s found the time to do documentaries on Val Lewton and Elia Kazan as well as writing criticism and currently serving as director of the New York Film Festival, was approached to direct the film, ‘I jumped at the chance’ in part because ‘I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad Hitchcock movie. Hitchcock’s deeply invested in every single one of his films. For someone who’s got that big a body of work, Hitchcock and Jean Renoir are alone.'”

Anne Thompson asks Jones how he went about choosing his interviewees, which include, besides those McCarthy mentions, David Fincher, Paul Schrader, Richard Linklater, Peter Bogdanovich, Olivier Assayas and Arnaud Desplechin. “I wanted people who would be articulate and also say something surprising,” Jones responds. “Whenever Marty talks publicly he likes to surprise people.” Thompson asks, “Why focus so much on Psycho and Vertigo?” Jones: “That’s where the energy went… It’s where the people interviewed were going… Vertigo and Psycho are about the movies but they also represented something more. Vertigo for Hitchcock is his creative id movie, that’s a big theme, about him as an individual artist. Then Psycho is something else.” His own favorite happens to be Thompson’s as well: Notorious.

Updates, 5/22: “Like the book, Hitchcock/Truffaut is a work of annotation par excellence, with in-depth examinations of scenes in The Birds, Vertigo and The Wrong Man,” writes Ben Kenigsberg at RogerEbert.com. “The movie is even illuminating on more mundane matters, such as the way Hitchcock staged some of the famous photographs that Philippe Halsman took of him and Truffaut. The subject matter is irresistible, but Jones laces it with a sly critical statement. The movie offers an implicit defense of later works like Topaz, perhaps in answer to a question that Hitchcock asked of himself: Had he been adventurous enough? Had he become a prisoner of his own form?”

“There’s nothing rarified about the air the project breathes,” writes Screen‘s Fionnuala Halligan. Hitchcock/Truffaut “features passionate people who have made their own iconic cinema talking about two giants of our film age with an enthusiasm which is infectious…. Hitchcock’s amusing attitudes towards actors also get an airing. It’s this kind of detail and human touch which makes this small, lovely project… into a film with a wider appeal and not just an academic examination which preaches to the converted.”

Update, 5/23: “The unique aspect of this documentary is that it has the license to have each man cast a new light on the other, but if that ever was Jones’s avowed aim, it is only partially successful,” finds Jessica Kiang at the Playlist. “Not to be churlish, because these are wonderful first-person anecdotes from filmmakers I love about a filmmaker I adore, but it does feel comfy rather than hugely illuminating to hear Scorsese talk about Hitch’s high angles in terms of his Catholicism or to have Fincher wax lyrically about the glass floor in Sabotage.”

Update, 6/6: Variety‘s Peter Debruge: “Whereas Hitchcock often focused on the nuts and bolts of film directing, asking to go off the record whenever things got too close to home (as with a question about his Catholicism), the insights offered by such eloquent admirers as James Gray and Olivier Assayas reiterate how the director’s best films work on multiple levels: as white-knuckle entertainment; as marvels of composition, light and space; as insights into his own personal preoccupations; and as poetic expressions of certain universal human anxieties.”

Update, 6/13: “Hitchcock/Truffaut respects its viewers enough to summon up suggestive and subtle links between sequences, between image and commentary,” writes David Bordwell. “Often there’s no title marring the images, so they stand out with a hallucinatory purity. Often a clip starts to play before the commentary kicks in, all the better to let the imagery strike us in its integrity; only then do we get the connection to what came before. The extracts are the prime movers, with the text snapping into place to catch up…. Kent Jones’s film opens up the Hitchcock—Truffaut relationship in fresh ways, and it stirs us to follow up the ideas that intrigue us. It’s the most stimulating film about a director that I’ve ever seen, teaching you about not just Hitchcock but cinema in general.”

And between those two quotes, there’s this: “I can’t think of another book on the cinema that has had its influence. Let me count some ways.” And those ways are, of course, expertly elaborated on.

Update, 11/27: For a piece in the New York Times on both the book and the film, Ben Kenigsberg talks with Kent Jones as well as Martin Scorsese, Christian Petzold, David Fincher and Whit Stillman.

Updates, 12/1: At the AV Club, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky reminds us that, as a critic, Truffaut had been “part of a group called the ‘Hitchco-Hawksians,’ on account of their constant stumping for Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. All Hitchcock had to bring to the conversation was himself, while Truffaut supplied an opinionated fan’s mindset and a real curiosity about what made his favorite movies tick. The result is still the best introductory text there is about the ins and outs of film as a popular art form. What Jones does is respect the ease of the source material, in which heavy ideas about how and why we watch movies are carried along by the flow of conversation.”

“Speaking with something like divine fervor, Scorsese puts the best possible face on today’s passionate, almost universal lionization of ‘ol Hitch,” writes the Voice‘s Alan Scherstuhl. “He’s ecstatic, but he’s focused on the craft of mastery rather than the simple fact of it. At its best, this Hitchcock/Truffaut is, too.”

Fresh interviews with Jones: Patrick Z. McGavin (RogerEbert.com) and Steven Mears (Film Comment).

Updates, 12/3: “Hitchcock is at his zenith and the New Wave is everywhere because the New Wave provided the very core of understanding that’s at the basis of more or less all movie appreciation today,” writes Richard Brody. “Writing in the New Yorker about Truffaut in 1999, I expressed dismay and displeasure in the films that Truffaut subsequently made, under Hitchcock’s often-conspicuous influence. I was wrong to disdain these films. Since then, I have come to love and admire many of them, not least because of the tension between compositional severity and spontaneous impulse that they reflect. Truffaut taught himself, with great effort and great difficulty, to film with a second voice, to become exactly the kind of director that he admired and that Hitchcock exemplified: he placed his first-person confessional voice, and even his actual speaking voice, into conflict with the virtual voice of subtext and symbol.”

“Disappointingly,” finds Jeanette Catsoulis in the NYT, Hitchcock/Truffaut “barely tickles Hitchcock’s fascinating fetishes. Despite a promising nod to the brilliant perversions of Marnie and Vertigo (which few can deny is one terrifically sick movie), Mr. Jones remains rigidly focused on hammering home the director François Truffaut’s motivation for writing the 1966 book.”

“This 80-minute film is in part a no-nonsense history lesson for the casual cinephile, managing not to get bogged down in minutiae while nonetheless feeling admirably thorough,” writes Benjamin Mercer in Brooklyn Magazine.

For David D’Arcy at Artinfo, Hitchcock/Truffaut is “a welcome contribution to film culture,” and, at Indiewire, James Franco discusses the doc with his “reverse self,” Semaj. Interviews with Jones: Steve Erickson (Studio Daily), Terry Gross (Fresh Air), Odie Henderson (Movie Mezzanine), Leonard Lopate (WNYC), Nick Newman (Film Stage) and Adam Schartoff (Filmwax Radio).

Updates, 12/26: At Eat Drink Films, Kent Jones writes about “The Films in My Life,” Pam Grady interviews him, Roger Leatherwood reviews Hitchcock/Truffaut and there are more thoughts from none other than Laura Truffaut, François’s daughter.

“Others have noted the absence of any female directors among the interviewees, which is unfortunate, since Hitchcock’s work is so fraught with sexual tension,” writes Bilge Ebiri at Vulture. “At one point, James Gray fascinatingly breaks down the male gaze in Vertigo, making the point that Jimmy Stewart’s gaze is the only one that matters in the film—since the whole movie is a ruse designed to rope him in through his attraction to Kim Novak’s character. And yet the writer Lauren Wilford recently explored the flipside of this notion in a wonderful essay called ‘Possessed: Vertigo Through Her Eyes.’ That’s not a knock on Gray’s incisive analysis, or Jones’s excellent film. Rather, it’s further proof of how vital Hitchcock’s work remains for so many after all these years. This film is a worthy contribution to that legacy.”

“You sometimes wish for more Truffaut—and perhaps, more of his contemporaries,” suggests Jonathan Romney in Film Comment. “In emphasizing how much Truffaut’s book did for making his hero respectable, it arguably underplays the work done by Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol in their 1957 book on the director, which Truffaut acknowledges in his introduction.” That said, the doc’s an “elegantly economical study.”

“At first blush,” writes Carson Lund at Slant, “Jones, who’s often a formally adventurous prose stylist, seems content with a frustratingly conventional assemblage of handsome talking heads, archival footage, and rudimentary photo scans…. Quirks in editorial timing and emphasis, however, gradually become evident…. In each scenario, Jones implicitly nods to the inexhaustibility of these films: Exegesis is possible and rewarding, even as the material force of the films themselves resists getting pinned down by words.”

More from Katie Kilkenny (Los Angeles Review of Books), Robert K. Lightning and Elias Savada (both at Film International). More interviews with Jones: Brian Crosby (Dork Shelf), Andrea Gronvall (Movie City News), Craig Hubert (Artinfo) and Vadim Rizov (Filmmaker).

Cannes 2015 Index. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.