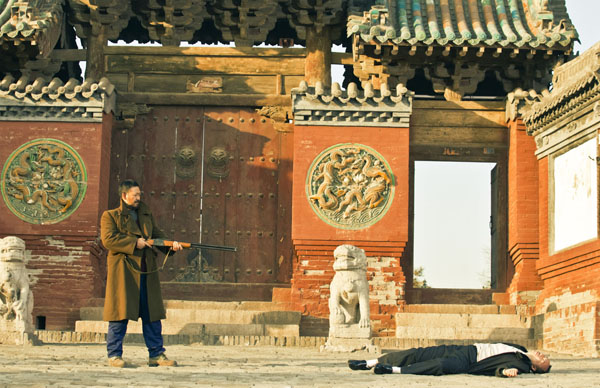

Jia Zhangke‘s A Touch of Sin “is a corrosive depiction of the New China, an everything-for-sale society still figuring out how to cope with the dehumanizing effects of unbridled capitalism,” writes Kenneth Turan in the Los Angeles Times. “In order to best portray an entire country growing faster than its socio-political structures can handle, a place where nothing speaks louder than money, filmmaker Jia has put together an omnibus film of four separate but linked stories, including one about a sex worker in a ultra-high-end brothel. The kicker is that all of them are based on real events that the filmmaker says in the press notes ‘are well-known to people throughout China.'”

The must-read essay on this one for now is going to be Marie-Pierre Duhamel‘s in the Notebook, an excavation of the film’s deep roots in the history of Chinese cinema: “Many comments will no doubt be made about a ‘new’ trend in Jia Zhangke’s cinema. As he himself puts it, Tian zhu ding is a ‘martial arts film for contemporary China,’ paying direct homage to director Hu Jinquan (King Hu, as went his name in the West) and nourished by the vision of martial arts films like those of Chang Cheh. The English title A Touch of Sin is a direct reference to Hu’s English title for Xianü (Lady Errant Knight) or Touch of Zen, a 1970 film, selected in Cannes in 1975. Murder and weapons have entered Jia’s world. But beyond any consideration upon ‘new’ or ‘renewal,’ Tian zhu ding appears so strongly rooted in a set of themes, characters and concerns that run through Jia’s filmography that its most striking beauties may well be in the consistency and strength of his film world.”

In Slant, Jordan Cronk notes that this is “the Chinese iconoclast’s first studio film in a career of independent productions. Prior to his great 2004 film The World, his work wasn’t even sanctioned by the Chinese government, so pointed was the critique of his homeland. Since that time, Jia has spent time working in both the documentary form (Dong; I Wish I Knew) and through something approaching both documentary and narrative cinema (Still Life; 24 City), effectively—almost imperceptibly—combining devices from each in an effort at constructing an altogether new hybrid. In some ways, then, A Touch of Sin feels like the film many may have expected to follow something like The World. In every other conceivable way, however, Jia’s latest represents new, uncharted stylistic frontier, one littered gunplay, knife fights—even an explosion.”

Even so, “A Touch of Sin eventually moves back to the calmer, realist cinematic language more associated with this director in its final act,” notes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “And the film is in any case not simply a racy adventure in exploitation, but an angry, painful, satirical lunge into what the director clearly sees as the dark heart of modern China, and a real attempt to represent this to audiences elsewhere in the world. He sees China as a globalized economic power player suffering a new and violent Cultural Revolution of money-worship in which a cronyist elite has become super-rich in the liquidation of state assets, creating poisonous envy in the dispossessed who hear all about others’ wealth from the internet, and are supposed to gossip aspirationally about it on their mobile phones…. This is a bitter, jagged, disaffected drama, pessimistic about China, pessimistic about the whole world.”

Variety‘s Justin Chang finds A Touch of Sin to be “unquestionably Jia’s most mainstream-friendly work, if also his most schematic and, blades aside, least penetrating; its ripped-from-the-headlines relevance is decidedly at odds with its giddy geysers of blood.”

For the Hollywood Reporter‘s David Rooney, the “tonal inconsistency, lethargic pacing and a shortage of fresh insight dilute the storytelling efficacy of this quartet of loosely interconnected episodes involving ordinary people pushed over the edge.”

“Its seductive aesthetic—while preserving some of the director’s cherished naturalism—is a riposte to the elaborate frames of Jia’s Fifth Generation predecessors,” suggests Fionnuala Halligan in Screen.

A Touch of Sin is scoring quite well so far on two critics’ grids, one at Critic.de, the other at Ioncinema.

Updates: “To be clear,” writes the Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin, “A Touch of Sin is not a kung fu movie, and the flying roundhouse kicks its characters endure are mostly metaphorical. There are, however, frequent flashes of very tough violence, and two of the tales climax in roaring rampages of revenge that will enthrall and delight your inner Quentin Tarantino.”

“These genre flirtations don’t exactly come naturally to the director,” finds Guy Lodge, writing for Time Out: “one driven-to-the-brink character clutches a knife in her fist with stiff unfamiliarity, and Jia shifts tonal gears just as mechanically. If the final effect is somewhat less nuanced than his previous work, it’s a good deal more vigorous.”

The festival‘s posted notes from the press conference.

The four stories, as laid out by Mike D’Angelo at the AV Club: “In the first, a pissed-off coal miner exacts Death Wish-style revenge on the corporate functionaries who ignore him; story two involves the murderous exploits of an itinerary worker; Jia regular Zhao Tao stars as a massage-parlor hostess pushed to the brink in part three; and the last segment sees a young man fail miserably in his attempt to start a new life in a new town. Each of these tales, except perhaps the final one, is horrifically compelling for its own sake, and the sheer visceral intensity lends an extra frisson for those familiar with Jia’s generally sedate nature.”

Time Out New York‘s Keith Uhlich: “The copious carnage is so outlandish (guns blow heads to gory smithereens; a fruit knife is wielded with skin-slashing, wuxia-flavored fervor) that it often feels designed to satiate audience bloodlust rather than challenge it. Plus, none of the filmmaker’s project has ever felt this plotted; at worst the rinse-wash-repeat nature of the tales come dangerously close to Babel territory in their on-the-nose attempts to diagnose the numerous ills of a rapidly modernizing China.”

“Possibly the most stunning segment involves a young man who comes to represent China’s newest generation,” writes Glenn Heath Jr. at Press Play. “After finding temporary work in a high-end brothel, Xiao Hui (Luo Lanshan) attempts to court one of the girls, seemingly with the most noble of intentions. Ironically, his advances are stunted not by a lack of emotional connection or love, but by the girl’s desire to remain ingratiated in the economically comfortable cycle of her work life.”

“Jia argues unambiguously that the country’s oppressive social conditions are fomenting inexorable rage,” writes Wesley Morris at Grantland. “He’s saying that the fantastical movie violence that for so long has been relegated to ancient times or to the organized-crime genre has the potential for outbreak in the offscreen present.”

Updates, 5/18: Daniel Kasman in the Notebook: “Yu Lik-wai’s camera both documents the world—factories, roads, cities, construction, nightclubs—and records Jia’s fictional situations founded in that reality, injustices served on levels ranging from the personal (female and relationship abuse) and economic (corruption through progress) to societal (working conditions, village politics). Much of the content of this reality is readily rendered into the international art cinema’s lingua franca of national critique, where allegory is commonplace, each relationship becomes representative of larger concerns, all passing conversations pique touchy contemporary issues, and lingering camera movements make sure to contain the importance of each and every real location. It is an approach risking heavy-handedness, schematism, and a pandering obviousness, yet the sharp, straightforward clarity and mobility of these images and words flow effortlessly between these two modes of realism-based storytelling and quietly grandiose metonymic exposition. Jia’s elegance again triumphs.”

“According to Jia,” notes Richard Porton at the Daily Beast, “many martial arts films ‘have a political thrust…[One] basic theme is repeated over and over again: an individual struggle against oppression in a harsh social environment.’ It now remains to be seen whether A Touch of Sin, which seems like an audaciously critical film to Western eyes, will achieve wide distribution in China.”

At Little White Lies, David Jenkins finds Jia “exploring pet themes through a new lens and demonstrating that even a superficial saunter into more generic territory can still feel fresh and new.”

For Jessica Kiang, writing at the Playlist, the “sudden bursts of gory, graphic violence sit oddly alongside the ultra-restrained nature of Jia’s sensibility, giving the film an odd rhythm that never really synthesizes into a coherent whole.”

Updates, 5/19: At RogerEbert.com, Barbara Scharres notes “the stylistic influence of Office Kitano, the production company of Japanese director/star Takeshi Kitano, one of the production entities behind A Touch of Sin. In the course of several audacious and murders that take place in the four stories, the deadpan acting style of Beat Takeshi is a clear reference. Many will disagree, but I would almost be tempted to call this film a black comedy, although only in the darkest and most diabolical sense.”

Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir argues that “anyone interested in the current state of China should see it, and it may open up this remarkable filmmaker to a larger audience.”

“Five territories have been sold and another 16 are under discussion or in the final stages of negotiation, sales company MK2 announced Sunday on the Croisette.” John Hopewell reports for Variety.

Updates, 5/20: When Manohla Dargis interviewed Jia for the New York Times, he “explained that the story’s four locations provided him a lot of visual options. The first section—which features an aggrieved miner walking down a dusty street as lonely as any John Wayne traveled—’is in Shanxi, in the north,’ he said, adding that it ‘is basically the Wild West, it’s very manly, very empty.’ Elsewhere, Mr. Jia picked locations that evoke the landscapes of traditional painting and martial arts films, and that taken together allowed him to ‘paint the face’ of China. His sampling from classical painting, Chinese operas and martial arts cinema suggests that it is a face that in some ways remains much the same, despite the country’s rapid modernization. ‘I feel that after centuries, nothing has changed,’ Mr. Jia said. ‘We’re just repeating the same fate.'”

For Kieron Corless, dispatching to Sight & Sound, A Touch of Sin “worked, mainly for its ability—as always—to intuit and convey some sense of the larger processes shaping these violent individual responses to a hostile, alienating economic climate. It’s hard to think of another director better than Jia at framing his characters in their environments: geography is destiny, you might say.”

Update, 5/21: Kino Lorber has picked up US rights. Rhonda Richford has details in the Hollywood Reporter.

Update, 5/22: Gavin Smith in a Film Comment roundtable: “I definitely felt A Touch of Sin got Jia out of the rut he was getting into with the last few films, and it takes his filmmaking to a whole other level. What was interesting about the violence was it didn’t remind me of Kitano, or anyone else particularly. There is an abruptness to it, and I think he’s also accelerating the frame rate or skipping a few frames in those brief images of bullet impacts. It’s very striking, and I’ve never seen it done before.” And Marco Grosoli: “There’s a very subtle interplay between continuity and discontinuity: the violence is just a stand-in for discontinuity.”

Update, 5/24: Tim Grierson in Paste: “Although hardly frothy or a celebration of violence, A Touch of Sin is remarkable in that Jia rather sardonically points out that, more often than not, his characters’ lives are improved (albeit briefly) by the violence they embrace. It’s a stunning commentary on why our collective belief in might makes right continues to prevail: Violence gets results in ways that more peaceful behavior doesn’t…. Sadly, A Touch of Sin isn’t a movie that will have any trouble translating to other cultures. If anything, it’s upsetting how much Jia’s dark tale of murder, retribution and suicide echoes similar issues within America’s contentious class system.”

Update, 5/25: Mary Corliss for Time: “The film’s dramatic impact may be muted, perhaps murky; but Jia has painted a national fresco with an epic, instructive reach.”

Updates, 5/26: Todd McCarthy in a Film Comment roundtable: “I talked to some Asian experts because he’s being pretty clear here about the social changes, the political changes that aren’t good. But my Asian expert friend said that we may not have seen this kind of material in widely exported films, but it’s actually been present in domestic films. There are these kinds of export-art films, and then there’s the rest, which we mostly don’t see. For outsiders it looks kind of bold, but according to my friends, it’s kind of common right now.”

Jia’s won Best Screenplay.

Update, 5/27: “As always, this is a filmmaker who assumes the role of witness and conscience in a society characterized by convulsive change and a growing amnesia,” writes Dennis Lim in a profile for the Los Angeles Times. “In an ever more materialist society, where a booming economy has swept many to prosperity but left untold others behind, Jia is unmistakably on the side of the have-nots…. As he was writing the script, he realized that the stories he was telling were compatible with the wuxia, or martial arts, genre…. ‘For me, martial-arts movies are deeply related to politics,’ Jia said, adding that this was especially so with King Hu’s films, which were often about ‘how individuals reacted to political oppression in the Ming Dynasty.'”

Updates, 5/31: “This is not Intolerance,” writes Patrick Z. McGavin at Film Journey: “the stories never exactly interweave, but they definitely exist in relation to one another. The great Yu Lik-wai, Jia’s regular cinematographer, working in in the unusual format ratio of 1:2.4, weaves together one dazzling, immersive image after another, to the point they collate and dance in the imagination. The use of color, especially red in the first chapter, is expressive and suggestive, binding shape and color and movement…. A Touch of Sin is the work of an angry man, but it has a throbbing acuity and tension.”

Patrick Brzeski interviews Jia for the Hollywood Reporter.

Cannes 2013 Index. And you can watch over 100 films that have seen their premieres in Cannes right here on Fandor. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.