“What is childhood if not an island cut off from the grown-up world around it, and what is first love if not a secret cove known only to the two parties caught in its spell?” asks Variety‘s Peter Debruge in an early review of the film that’s opening the 65th Cannes Film Festival. “While no less twee than Wes Anderson’s earlier pictures, Moonrise Kingdom supplies a poignant metaphor for adolescence itself, in which a universally appealing tale of teenage romance cuts through the smug eccentricity and heightened artificiality with which Anderson has allowed himself to be pigeonholed…. While Anderson is essentially a miniaturist, making dollhouse movies about meticulously appareled characters in perfectly appointed environments, each successive film finds him working on a more ambitious scale. Co-written by Roman Coppola, Moonrise Kingdom may not be set anywhere so exotic as a Mediterranean boat (The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou) or a trans-Indian train (The Darjeeling Limited), but it feels even more finely detailed than any of his previous live-action outings. Still, the love story reads loud and clear, charming those not put off by all the production’s potentially distracting ornamentation.”

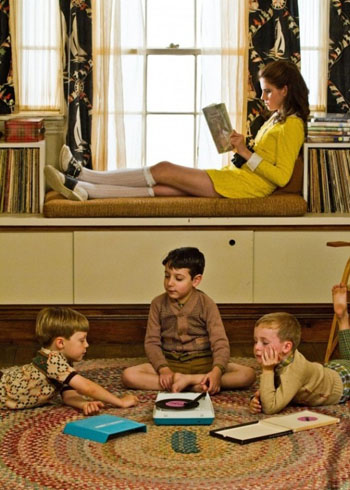

“Even more than in his previous work, the dialogue and music possess an extreme degree of declarative definitiveness that works as an aural correlative to the visuals,” writes Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “Everything is in a box—a beautifully wrapped one, at that—allowing for no relaxation, casualness or spontaneous combustion. Except combustion is what takes place between Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman), a brainy orphan Scout, and Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward), the odd girl out in a family with three preoccupied younger boys, a checked-out dad (Bill Murray) and a mother (Frances McDormand) having an affair with a milquetoasty local cop, Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis). A general panic is sparked when Sam goes AWOL from Camp Ivanhoe to run away with Suzy.”

Time Out London‘s Dave Calhoun will grant that “some of Anderson’s films, especially his last live-action work, The Darjeeling Limited, have felt too heavy on the furnishings and light on feelings, this one is so much more free, fresh and soulful…. This is an American story but it has an unmistakeable French flavour to it. The 1960s setting, the kids on the run and the wild plotting (a bit too wild in the final third), all give it a nouvelle vague feel. It’s an American Pierrot le Fou refashioned in retrospect with Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo as pre-teens.”

“Working with his long-time cinematographer Robert Yeoman, the director succeeds in turning young love into precisely the intense, transitory, impossibly idyllic sensation it can be in real life,” writes Tim Grierson for Screen. “Utilizing the Rhode Island locations to good effect, Moonrise Kingdom is like a live-action storybook of open skies and empty terrain in which Sam and Suzy can run free, creating a new life away from the sadness of their previous existence. Very consciously, Anderson signals the fact that this Eden can’t last, which gives the film such poignancy.”

Besides the trailer, there’s quite a lot of viewing out there to busy yourself with until Moonrise Kingdom opens in the States and parts of Europe on May 25. The official YouTube channel collects no less than five featurettes and six clips, all narrated by Bob Balaban. The Cannes Film Festival itself has collected a series of clips from Anderson’s earlier films illustrating his use of music. And Slate‘s Jacob Weisberg interviews Anderson; there are two parts. First, he’s got his own questions, and he then follows up with questions from readers. Anderson discusses, among other things, the influences on Moonrise, including Susan Cooper‘s series of books, The Dark Is Rising, and, musically, François Hardy, Benjamin Britten, and Leonard Bernstein.

More interviews with Anderson: Cath Clarke (Time Out London), Gregg Kilday (Hollywood Reporter) and Dennis Lim (New York Times).

Updates: The Telegraph‘s David Gritten: “If its ending feels faintly messy and rushed, Moonrise Kingdom (the name Sam and Suzy give their secret hideaway) is a worthy addition to Anderson’s canon—his deadpan wit meshes nicely with a generous view of human imperfections. A mood elevator of a movie, it’s an ideal opener to a sunny, blue-skies Cannes.”

“All the characters feel like they’re either older or younger versions of Anderson’s past creations,” writes David Jenkins at Little White Lies. “Murray retools that straight-from-the-golf-course-bar turn he perfected in Rushmore; the kids all feel like Tenenbaum juniors… Jacques Tati comes to mind at several points, not least due to the feeling that you’ll need to watch the film over and over to be able to unlock the jokes occurring in the background of each scene… [W]ith Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson has made a film about youth that feels like it was ripped from the overactive imagination of a 12-year-old. It’s like a Prairie Home Companion version of Romeo and Juliet as made by a raffish aesthete.”

The BBC’s Kev Geoghegan has notes from the press conference, including Anderson’s comments on working with Bill Murray: “He’s just about the best person you could ever hope to have on a set with you. He’s a great ally, in my experience anyway, he’s someone you can rely on. You can say, ‘There’s a problem. Can you deal with this?’ And he’ll think of a way and go and handle it. Because he’s so funny, he’s the kind of person, if there was a mob that was going to try and destroy something, he’s one of the few people you could send to stop the mob and, depending on the circumstances, he’d have a very good shot.”

“It’s fun watching Anderson manipulate this superb cast, who deliver delicious, precisely scripted comic moments surrounded by such archaic 1965 props as walkie-talkies, megaphones and person-to-person split screen phone calls.” Anne Thompson: “As a sign of the times, the movie is one of the few in the festival shot on film (super 16). Anderson admits that it may be his last, as Technicolor stops processing film and the world goes digital. ‘Maybe there’s a great app that makes it look like film,’ he said, ‘but to my mind there is no substitute.'”

HitFix‘s Drew McWeeny finds that, with Moonrise, Anderson’s “at his very best, energized by the subject matter and blessed with a cast that came ready to play.”

“Among the filmmakers to emerge at the turn of the 21st century, Anderson was an intriguing oddity—lacking the grand ambition of Paul Thomas Anderson, the range and prolificacy of Soderbergh; shorter on hipster cred than Jonze or Gondry. Yet his aesthetic has been the most pervasive of all,” argues Tim Walker in the Independent. “As Tarantino defined the 1990s, so Anderson quietly claimed the 2000s. Some might argue that Anderson (PT) or Alexander Payne are equally influential, but their impact is hard to measure. Anderson (W)’s stylistic tics are unmistakable.”

“Nobody steals the show more than Bob Balaban in a handful of scenes as the local scientist predicting a storm that sets the stage for a dramatically exaggerated climax,” writes indieWIRE‘s Eric Kohn. “But Anderson movies have less to do with clever story twists than the relish the filmmaker brings to them. Within its first 15 minutes, Moonrise Kingdom nimbly employs a split screen, first-person mode of address, scenes flush with color schemes to indicate various moods and personality types, abruptly funny flashbacks and a camera that nimbly tilts from right to left—as if the entire Andersonian universe existed on a comic strip zipping before our eyes in real time.”

“Where David Lynch finds a dark horror beneath the wholesome exterior, Anderson sees something else—something exotic but practical and self-possessed, a world that ticks along like an antique toy, much treasured by a precocious child.” The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw finds that Anderson’s “homemade aesthetic is placed at the service of a counter-digital, almost hand-drawn cinema, and he has an extraordinary ability to conjure a complete, distinctive universe, entire of itself. To some, Moonrise Kingdom may be nothing more than a soufflé of strangeness, but it rises superbly.”

“Moonrise Kingdom‘s opening scenes are vintage Wes Anderson,” writes Budd Wilkins at the House Next Door. “A series of pans and lateral tracks explores the Bishop household in studied tableaux, each isolated member of the family captured in their native habitat, while on a 45rpm record a disembodied voice guides listeners through the works of Benjamin Britten. Likewise, there’s a narrator (Bob Balaban) to guide us through Anderson’s film, in just one of many recursively referential (and, at times, painfully self-aware) touches. Examples could be further multiplied, but let’s stick with the Britten: Not only does his music recur in the epilogue that effectively bookends the film, but Britten’s opera Noye’s Fludde, itself based on a medieval mystery play (see the Chinese puzzle box pattern emerge?), serves as an objective correlative for the acts of God or nature that dominate the second half. As the recorded voice intones late in the film, ‘Britten has taken the orchestra apart and now puts it back together again.’ Much the same could be said for Anderson’s direction and script work with co-writer Roman Coppola.”

“If anything defines all of Anderson’s work,” writes James Rocchi at the Playlist, “it’s that the kids seem awfully grown-up, and the grown-ups seem awfully childish. Sam and Suzy want to be adults, and know they aren’t there yet; the adults around them, in their own unhappy lives, seem to be looking on and saying ‘slow down.’ When Sam makes an excellent point, Captain Sharp sighs. ‘I can’t argue with you; then again, I don’t have to: You’re 12 years old.’ The film has the loose, playful feel of a light opera—the island’s name is no coincidence—but it’s interesting how the stakes stay high even as the leaping and laughing crank up to full-speed.”

“No matter how discontent Anderson’s latest film’s protagonists might feel, they are always in concert with the people who care for them,” notes Simon Abrams at Press Play. FirstShowing‘s Alex Billington: “This is one I liked, but didn’t love.”

You can listen to the press conference here.

“As self-contained and narcissistic as, well, Cannes itself, Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom proved to be a perfect opener for the world’s most important festival in its venerable 65th year,” writes Michal Oleszczyk at Hammer to Nail. “If anything, the director’s return to live action filmmaking after the successful 2009 adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox only amplified his near-obsessive fastidiousness. So much so that Moonrise Kingdom can be counted as one of his best-controlled and most sustained efforts to date—even if after the movie is over you may feel you witnessed just one or two perfectly laid out shots of beautifully patterned paraphernalia too many.”

“Portraying Sam’s scoutmaster, who knows enough to hold his ever-present cigarette well away from a cache of fireworks, Edward Norton proves to be the cast’s ringer, perfectly at home with the stylized precision of Anderson’s preferred playing style,” notes the Chicago Tribune‘s Michael Phillips.

“Plenty of films detail first love, but nothing short of George Roy Hill’s sweet A Little Romance (1979) has captured it with quite the originality and freshness of Anderson’s work here,” finds Pete Hammond at Box Office.

At the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Eugene Hernandez reminds us that the film’s set in 1965: “When the two young stars fall in love for the first time, the looming sense of what’s coming hangs over their burgeoning passion just as the society they are maturing into is about to see its own cultural shifts. ‘These characters are 12,’ filmmaker Wes Anderson explained, ‘When they are 18 they are going to be in a very different kind of America, I think. After so much stasis, there was change.'”

“When they run away, Suzy brings a kitten, a suitcase full of books about girls who have adventures, and a treasured pair of binoculars,” notes Kristin M. Jones in Film Comment. “Sam wears his dead mother’s pearl brooch, pinned to his uniform. Shadows seem to follow them, especially at moments when Moonrise Kingdom evokes darker movies. The armed Khaki Scouts who chase them through the woods are reminiscent of Lord of the Flies… But Suzy and Sam remain safe, as if they are children protected by a spell in a fairy tale.”

Updates, 5/17: “In March and April 2009, Moving Image Source published a five-part series by Matt Zoller Seitz on Wes Anderson’s style and influences.” With the retrospective Wes Anderson’s Worlds slated to run at the Museum of the Moving Image from tomorrow through May 27, the Source has reposted the series in full. Definitely recommended.

“Words are to The Royal Tenenbaums what the horse and carriage are to The Magnificent Ambersons,” argues Joseph Jon Lanthier at the L: “not entirely useless, but gawkily atavistic, and often more harmful than helpful. Anderson implies, as Welles would never, that growth is capable after this shock of violence brought about by words, but the healing process is largely non-verbal. There are Rolling Stones LPs and yellow pup tents, and montages of Manhattan shenanigans set to Paul Simon. Where Welles was content to let his narratives stew in the hell of meaningless language they’d created for themselves—think of Kane’s dying words—Anderson provides relief. His answer to literature is pop culture.”

Back to Moonrise Kingdom, though. At the AV Club, Mike D’Angelo finds it “hard to imagine any consistent fan of Anderson’s work not surrendering to its trademark amalgam of precision and melancholy. Like Rushmore, it earns its pathos by juxtaposing youthful idealism with adult resignation.”

“Anderson’s cinema contains a peculiar mix that makes it an ideal opening night vehicle,” writes Robert Koehler at Film Journey. “There’s a kind of absolute auteurism, a hyper-aggressive formalism, an insistence on the camera’s view as a proscenium arch inside of which an entirely theatrical universe is created, alongside a lightness, a preference for melancholy swathed in the scent of vanilla, sadness as a weekend romp, the melodramas of parents and the children they don’t understand as storybook fantasies.”

“Part of the considerable appeal of Moonrise Kingdom,” finds Time‘s Richard Corliss,

“is its notion that two of Anderson’s dolls want to bust out of his stylistic straitjacket…. In his Hollywood Reporter review, Todd McCarthy describes the movie’s plot as ‘They Live by Night with 12-year-olds.’ Another late-’40s tale of romantic doom shares this movie’s title: Frank Borzage’s Moonrise, about an older young man (Dane Clark) on the rural run and his love for a more upscale girl (Gail Russell). Gilman and Hayward, both new to the screen, must feel their way to acting as Sam and Suzy grope toward love; the two performers’ are as naïve and winning as the characters are solemn, willful and 12.”

Guy Lodge at In Contention: “It’s the most openly sentimental story hook of Anderson’s career, promising a work of rare emotional availability from the tweed-suited archduke of archness—so why is it that Moonrise Kingdom, stuffed as it is with moments of zonked wit and lightning-bug beauty, still feels so hollow, so lacking in truth or spontaneity? Perhaps because fastidiousness—fussiness, if you’re feeling less charitable—is part and parcel of Anderson’s art: with each individual frame composed and art-directed to the nth degree, the film finally lacks the porousness required to convincingly convey less disciplined or less rational urges.”

For Time Out Chicago‘s Ben Kenigsberg, though, Moonrise is “terrific, simultaneously the apotheosis and refinement of the filmmaker’s brand. Applying his childlike flights of fancy to a legitimately childlike milieu, it’s his most harmonious balance of style and content since Rushmore.”

“Though lovely and on the beach, the post-premiere soiree for Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom was proving a bit of a snooze,” reports Jada Yuan at Vulture. So guess who saved the evening? Come on, guess. Bet you $10,000 you don’t need three guesses.

Updates, 5/19: In Slant, Andrew Schenker begins by addressing the opening scene—”it doesn’t take the director long to show why his films can never be reduced to the superficial elements which are all his many imitators seem capable of grasping”—and wraps with the hurricane towards the end: “Anderson’s showiest set piece to date manages to bring the expected visual splendor (with the bonus of spatial coherence) while giving each character his or her due, the director navigating the proceedings to a satisfying resolution.”

Moonrise “is one of Mr. Anderson’s supreme achievements,” declares Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “It’s wondrously beautiful, often droll and at times hauntingly melancholic.” At the L, Glenn Heath Jr. finds that it “represents Anderson’s transition toward a more instinctual way of exploring physical cinematic space. Shot on Super 16mm, Moonrise Kingdom is chock-full of grainy long shots accentuating Sam and Suzy’s elemental call of the wild. A private beach, an open field of green, and a steep cliff face are just some of the beautiful monuments filling Anderson’s zooms and pans with Western spirit.”

For Jordan Cronk, dispatching to PopMatters, it’s a “slighter, less thematically heavy film than some of Anderson’s best work.” At the Daily Beast, Richard Porton notes that it provides “ample ammunition for both the pro-Anderson and anti-Anderson camps.” Time Out New York‘s David Fear pronounces it “the Hipstamatic movie of the year—Anderson’s all-star ode to prepubescent precociousness is his least fussy movie in years, while still being a formalist’s wet dream.” In the Independent, Geoffrey Macnab finds it “surprisingly moving.” Jason Gorber at Twitch: “Moonrise is an absolute delight, and I shall fight anyone that feels otherwise.”

Ronald Bergan for Bright Lights: “Wes Anderson’s films always remind me of what Eric Blore says in The Gay Divorcee: ‘Oh, “whimsical” is much more whimsical than “whimsical”!’ This one is as ‘whumsical’ as ever.”

New interviews with Anderson: Francesca Babb (Guardian), Kyle Buchanan (Vulture), Tim Noakes (Dazed), and Anne Thompson (video).

Update, 5/20: Ignatiy Vishnevetsky in MUBI’s Notebook: “Anderson, it seems, has finally and thoroughly gone up his own ass—and yet the film happens to be one of his best and most inviting works. Moonrise Kingdom—deftly orchestrated but deliberately uncomplicated—is easily Anderson’s sweetest, most sincere movie, and the only one, aside from Rushmore, where the director’s stylistic and thematic conceits are perfectly in sync. It may be the twee-est, archest film of a director frequently accused of tweeness and archness, and it may veer closer than any of Anderson’s other films to outright kitsch (e.g. the brownish, Jean-Pierre Jeunet-style color grading)—but there is a grace and a beauty to the way all of its fussed-over parts click together.”

Update, 5/21: Just a video today, but it’ll more than do:

Updates, 5/26: Now that Moonrise Kingdom is in theaters, the reviews from critics back in the States are in: Richard Brody (New Yorker), Manohla Dargis (NYT), David Edelstein (New York), Steve Erickson (Gay City News), Kurt Halfyard (Twitch), J. Hoberman (Artinfo), Glenn Kenny (MSN Movies, 5/5), Patrick Z. McGavin, Andrew O’Hehir (Salon), Nicolas Rapold (L), Dana Stevens (Slate), Scott Tobias (AV Club, A), Elbert Ventura (Reverse Shot), and Stephanie Zacharek (Movieline, 6.5/10).

More interviews with Anderson: Brian Brooks (Movieline) and Oliver Lyttelton (Playlist). And the