Twitter was all a-flutter this morning following the first screening of Michael Haneke‘s Amour (Love). Raves in 140 characters or less were shooting out into a world eager for early verdicts on the first film Haneke’s made since winning the Palme d’Or in 2009 for The White Ribbon. The Guardian‘s Andrew Pulver has gathered a few of these, all of them variations on “best film at Cannes so far” and so on. I’ll add one more, from Mike D’Angelo, who gives the film a 77 on a scale of 0-100—which, for him, by the way, is a more than solid grade: “Starts out surprisingly lovely, then turns Haneke-grueling. But always deeply felt & beautifully acted, if singleminded.”

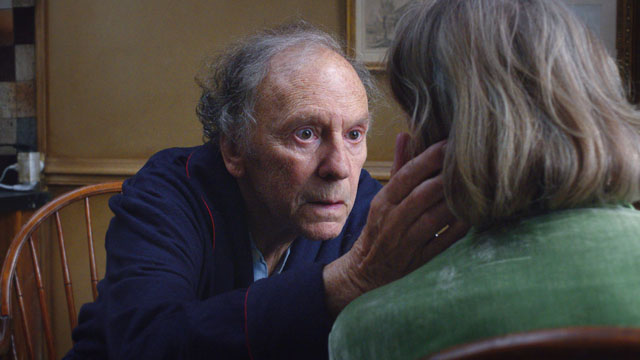

So naturally, I’ve been anxiously awaiting full reviews and it now looks like we have just enough of them to get started. The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw calls Amour “a moving, terrifying and uncompromising drama of extraordinary intimacy and intelligence. Amour asks the question of what will, in Larkin’s words, survive of us—and what the word means as we approach the end of our lives. Haneke begins the movie with a flash-forward sequence which impresses on our minds and retinas a devastating memento mori motif, governing how we react to everything that succeeds it. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva give breathtaking performances as Georges and Anne, retired music teachers in their 80s, living in a handsomely furnished, book-lined Paris apartment with a baby grand piano. They are happy, affectionate, loving; active and content…. But one day, Anne suffers the first of a series of strokes which paralyze one arm, making playing the piano impossible, accompanied by progressive dementia…. Having promised the terrified Anne that he would never put her in a home or hospital, Georges is placed under the increasing, insupportable strain caring for her at home.”

“It’s a staggering, intensely moving look at old age and life’s end,” writes Dave Calhoun in Time Out London. “Haneke rejects the idea of death as a communal experience and presents dying as intensely isolating. Georges and Anne’s daughter (Isabelle Huppert) and son-in-law (William Shimell) visit, but their own feelings and experiences are increasingly disconnected to what’s happening in this apartment…. Here, death creates a fortress, and it feels piercingly true…. Amour is a devastating, highly intelligent and astonishingly performed work. It’s a masterpiece.”

Variety‘s Peter Debruge: “By titling his film Amour, Haneke rebels against the way ‘love’ is traditionally associated with youthful passion onscreen, rejecting the context in which Riva used it describe her fleeting affair in 1959’s Hiroshima mon amour or the sort of lightning-strike crush Trintignant’s character experienced in 1969’s My Night at Maud’s. While such films depict the inferno of obsession, here, at the other end of both actors’ careers, love is a concept for adults, not pop songs, more likely to inspire weeping than to set the pulse racing.”

“Cinema’s arch Austrian schoolmaster has not gone soft on us,” David Jenkins assures us at Little White Lies. “You might see the film as a meticulously unsentimental response to works like Leo McCarey‘s Make Way for Tomorrow or Ozu’s Tokyo Story, as it filters the unavoidable demise of a human being through the prism of experience, memory, family, society, and most importantly, the consolations of companionship…. Love is a very hard film to fault, shot with immaculate precision by Darius Khondji, rhythmically edited and overloaded with nuance and delicately metered emotion. If there’s any criticism to be had it’s that the film is a tad too neat and unambiguous, introducing and developing its themes with a single-minded precision that makes you miss the pristine conceptual messiness of Code: Unknown or the implacable cine-riddles of Hidden. Still, this is an exceptional work shows a world-class director still unafraid to lock horns with the profound mysteries of the universe.”

“And anyone doubting that Haneke had the capacity to demonstrate genuine compassion for his characters will be startled to see that yes, the man behind both Funny Games can do emotional as well as he does cerebral,” writes Time Out New York‘s David Fear. “Critics up and down the Croisette have been going wild about it all day. When it hits American screens, you will too.”

In the Hollywood Reporter, Deborah Young notes that “everything is laid out in plain sight from the bang-on opening scene: the fire brigade breaks down the door of a spacious Paris apartment to find a long-dead old woman lying in bed, her head surrounded by flowers. The rest of the film is a claustrophobic flashback leading up to this moment.”

“What’s most surprising of all, then, is that, despite its death-haunted demeanor and foregone conclusion,” writes Budd Wilkins at the House Next Door, “this is easily Haneke’s most humane film….. Amour contains none of the moralistic finger-wagging and gratuitous sadism that so many critics have found off-putting in the director’s work. (Though I must admit that I am, by and large, an admirer of his films.)… The terrifically ambivalent ending, too, gives viewers something to chew on, without necessarily scratching their heads in bafflement, as many did at the end of Caché.”

“Although not exactly heartwarming, Amour has a more contained vision of human relationships than Haneke’s previous films without sacrificing its bleak foundation,” writes indieWIRE‘s Eric Kohn. “It’s his most conventional movie about death, and the most poignant.” And the Playlist‘s Kevin Jagernauth echoes many when he writes that “Trintignant and Riva deliver two of the best performances of the Cannes Film Festival so far.”

Alt Film Guide has collected and translated snippets from early reviews from French and Italian sites as well as one in English from John Bleasdale at Cine Vue, where he calls Amour “the first real masterpiece of the 65th Cannes Film Festival.” Of course, there’ll always be one, and in this case, it’s FirstShowing‘s Alex Billington, who simply “can’t stand it.”

Updates: The LA Weekly‘s Karina Longworth: “Haneke is the first Competition film director at Cannes this year to both succeed totally on the terms he sets out for himself, and truly challenge the audience to bear witness to something they’ve never seen on screen before: a realistically slow death, and all the unpleasantness it entails, depicted without sentimentality, to the point where when Huppert’s character breaks down in tears, Haneke films her with her back to the camera.”

“Like most of Haneke’s oeuvre, Amour strips down set design and audio cues to suit the film’s stark material,” writes Glenn Heath Jr. “Darius Khondji’s precise camera is at its best when slowly moving through the apartment foyer, or momentarily out into the hallway for a brilliantly realized dream sequence involving wet feet and an errant hand. But Haneke only delves into the surreal a few times, instead letting the ambient noises of Anne’s cries echo like a requiem in the cramped space. In many ways, the sounds of Amour are most essential, markers of disappearing time and waves of emotion slowly fading to black.”

Also writing for Press Play, Simon Abrams: “Amour‘s icy calm representation is of a piece with earlier films like The Seventh Continent and Lemmings, in that all three are characterized by existential despair. Nobody can intervene and save Georges from the nightmarish routine that Anne’s illness and his obsessive but un-sensationalized affection for her have forced upon him.”

Jonathan Romney in Screen: “More than in any of his other films, Haneke’s theatrical background is visible in the measured, controlled staging—in that, rather than dramatise the couple’s experience, he shows it to us, for this is a hyper-lucid demonstration of his theme.”

“[T]his is no soft-edged weeper like Away From Her in which we’re cued to get all misty and nostalgic as someone’s mind drifts sadly away,” writes Entertainment Weekly‘s Owen Gleiberman. “What’s far more devastating in Love is that Anne’s mind is mostly still there—and what it wants, what it needs, is for her to die.”

And then there’s this movie-worthy moment from Melissa Anderson, dispatching to Artforum: “At the press conference for Amour, a surprisingly tender movie from a filmmaker usually associated with sadism, Huppert seemed content to defer to Trintignant and Riva, two titans of French cinema, even while contradicting them…. She smiled slightly as Trintignant genially—but quite convincingly—said of Haneke, who was seated to his immediate left, ‘I’ve never met such a demanding director. [Working with him] is a very difficult task.’ Queried later, Huppert demurred: ‘Well, I don’t think it’s all that difficult. […] I like to watch myself in Michael Haneke’s films.’ But in response to a Chilean reporter’s question whether all actors in Haneke’s films suffer, her response was swift and unequivocal: ‘No, it’s the spectators who suffer.'”

Updates, 5/21: The New York Times‘ Manohla Dargis more or less makes it official. Amour is the “first masterwork” of Cannes’ 65th edition.

“For about an hour or so, I could scarcely believe I was watching a Haneke film, despite his trademark formal classicism and absence of overt sentimentality,” writes Mike D’Angelo at the AV Club. “There’s almost an ‘aww’ factor to Georges’ attentiveness following Anne’s first stroke, which ill-prepares you for the truly grueling compendium of slow deterioration to come. By the time she’s reduced to an immobile husk capable only of slurring the word ‘hurts’ over and over again, Haneke’s single-minded, unsparing approach will surely have wrecked you…and yet there’s also so much raw beauty in this paean to devotion, including several starkly poetic interludes (a strange nightmare sequence, a montage of landscape paintings) that have no logical/narrative explanation but nonetheless feel exactly right.”

“The entire film is a sustained feat of seamless editing that’s in fact quite bold in its rich (if casual) omissions,” writes Michal Oleszczyk at Hammer to Nail. “Time and again, scenes get nipped at the most unexpected moment, usually sparing us some instance of Anne’s humiliation or leaving a conversation unresolved and thus forever-hovering in our minds. The reaction shots we most expect to get simply aren’t there, as in the scene of Eva angrily demanding ‘a serious conversation’ about her mother’s condition, with Georges pointing out that one way to go for Eva would be to take Anne into her own apartment. Since that would be too much of a commitment, Eva recoils—but we never get to see the recoiling (which could have enabled us to pass a judgment on her passiveness), only its result—namely, the preserved status quo of Anne staying with her husband.”

Updates, 5/23: “Haneke has often meted out punishment to his characters; in Amour he provides a reviving coda.” Mary Corliss for Time: “In the history of movies about love, Amour lasts forever.”

“For once, the only cruelty present in a Haneke film is the ultimate cruelty of life’s end,” writes Sight & Sound editor Nick James.

For Ryan Lattanzio, writing at the Evening Class, Amour suggests “late Ingmar Bergman or Carl Theodor Dreyer: restrained, pensive and deeply felt.”

“Each conversation is laced with double-meaning, every word part of a power play,” writes Kaleem Aftab in the Independent. “Menace and conflict lurk in the shadows. The few metaphors when they come are simple, a pigeon in the house, a dream sequence and a montage of eerie landscape paintings, but by being more straightforward, Haneke’s morality tale is all the more powerful.”

Jason Bellamy and Ed Howard discuss Haneke at considerable length at the House Next Door. And finally for now, a bit of viewing. First, there’s Kevin B. Lee‘s new video essay, Highjacking Michael Haneke, here in Keyframe. And the Guardian talks with Haneke about the film, being in Cannes and winning awards.

Updates, 5/26: “No matter how shielded from our mortality by numerous defense mechanisms, even the serenest of us struggle to come to terms with the inevitable prospect of no longer being ourselves someday,” writes Boris Nelepo in MUBI’s Notebook. “The issue just cannot be dealt with the way Haneke does it—in a matter-of-fact, cold-blooded fashion, so that each frame screams art and invokes appreciation. His audience is not for a moment allowed to forget they are watching nothing short of a masterpiece. It is an ultimatum, really: either you acknowledge that, or you admit to your own insensitivity.”

“Author Jeffery Myers called George Orwell ‘the wintry conscience of a generation,'” notes James Rocchi at Box Office, “and it’s a phrase that could be applied to Haneke, as well. Love is hardly cold, but, the finale of the film is as unthinkable as it is understandable, an act of brutal grace that, like it or not, is far closer to reality than some Hallmark-level sentimentality or sudden cheap reversal that might let the audience leave on an ‘up note.’ Gorgeous and haunting, heartfelt and immensely thought-out, Haneke’s latest is hardly his masterpiece, but merely by seeing and showing what most directors can’t or won’t, it’s head and shoulders above the vast majority of dramas in the field, with the stark and startling vision that perspective allows.”

Dennis Lim talks with Haneke for the New York Times.

“Having just turned 70, Michael Haneke appears to be turning a new leaf in his abrasive view of humanity as being, for all its attempts at civilization, barely out of the jungle,” writes Robert Koehler at Film Journey. “At the same time, Amour is a bit too prim and proper, too buttoned-up, too designed to win end-of-the-year critics awards, too elegantly turned out to please. It’s a kind of art house movie parade, presenting all of the items that would directly please the Laemmle Theatre’s target audience (of a certain age, cultured, urban, old enough to recall Trintignant and Riva as A Man and a Woman). Haneke has made an honest film without sensationalism, but it’s also quite strategically programmed, down to the lust in its bones to win yet another Palme d’Or, which may very well happen.”

Update, 5/27: Amour‘s won the Palme d’Or.

Update, 5/28: Scott Foundas at the Film Society of Lincoln Center: “The story of the film was inspired by an event in Haneke’s own family—an elderly relative who took her own life rather than suffer a prolonged descent into infirmity—and the film’s setting is one that Haneke has now mapped more acutely than any other director working today: the lives of bourgeois European artists and intellectuals whose privilege fails to insulate them from the violence and horrors of everyday life. Indeed, despite the various critics who chided earlier Haneke films for their supposed finger-wagging moralism and chilly Protestant air, and who are now falling over themselves to praise Amour as the director’s most compassionate work to date, Amour is as much of a home-invasion horror show as Haneke’s earlier Funny Games. Only, in this case, the masked intruder is none other than death himself.”

Fabien Lemercier interviews Haneke for Cineuropa.

Update, 5/31: “Many have observed that Amour is Haneke’s most tender film,” writes Dennis Lim for Artforum. “True, but I don’t think that precludes it also being his most seamlessly manipulative. The central impulse of Haneke’s work—to confront his audience with something they would rather not contemplate (or, as is often said, to discomfit or even punish them)—is not mitigated here so much as totalized, given ultimate and universal significance. To call the film (which often feels like it was made for the express purpose of winning a Palme d’Or) undeniably affecting is also to acknowledge its screw-turning, Haneke-like aspect. How could anyone fail to be moved by this subject, or by Jean-Louis Trintignant, eighty-one, and Emmanuelle Riva, eighty-four, offering up their fragile bodies as well as the auras of their younger selves? Rarely has Jean-Luc Godard’s assertion that a film is a documentary of its actors been so vividly demonstrated. Watching Riva and Trintignant make their way to the podium at the awards ceremony Sunday night, I found myself no less touched, perhaps even more so, than while watching Amour.”

Cannes 2012 Index: a guide to the coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed.