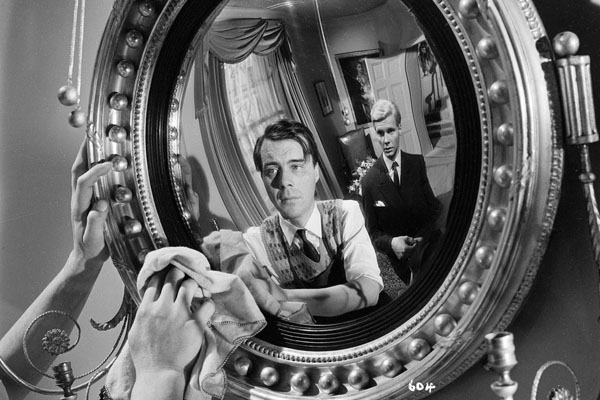

Following two entries with a similar bent (“Japan” and “France“), the occasion for this one is the current run of the 50th anniversary restoration of Joseph Losey‘s The Servant at Film Forum. Critics Round Up has collected a good handful of reviews appearing in the New York press over past couple of weeks, so here I want to sample a bit of what the British critics had to say when the restoration screened in London in March. “Fifty years after The Servant (1963) was first released,” began Geoffrey Macnab in the Independent, “it’s easy to forget quite how creepy and transgressive Joseph Losey’s film once seemed. The early 1960s was still an era of Norman Wisdom comedies like A Stitch in Time (also released in 1963 and a huge box office hit) and of rip-roaring war movies like 633 Squadron (1964). True, British cinema had its own ‘new wave’ of sorts led by Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz, making gritty new films in the north of England, but Losey’s movie wasn’t anything like The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner [1962] or Saturday Night and Sunday Morning [1960]. As scripted by Harold Pinter from a novella by Robin Maugham, The Servant played like a twisted, homoerotic 1960s version of one of P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves stories.”

The Guardian went all out for The Servant, in part because it’s a landmark film, of course, but also because Peter Bradshaw wrote an essay accompanying the restoration’s release on DVD and Blu-ray: “Homosexuality is everywhere and nowhere in The Servant. Harold Pinter’s superbly controlled, elliptical, menacing dialogue is able to hint, to imply, to seduce, to repulse, in precisely the manner that gay men were forced to adopt in 1963, when homosexuality was still a criminal offence, and when representing homosexuality on screen was forbidden. To locate the gay gene in The Servant, you have to go back to its source, the 1948 novella written by Robin Maugham, the nephew of W. Somerset Maugham. The Servant has its spark in an extraordinary event in Maugham’s own life, to be treasured by connoisseurs of British sex and class.” And of course, that’s a story he tells with relish in the following paragraphs.

The Observer‘s Philip French reminds us that 1963 was a very good year for British cinema. “John Schlesinger’s Billy Liar, Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life took local filmmakers into radically different directions. Two resident Americans—the self-exiled Stanley Kubrick and the McCarthy refugee Joseph Losey—established themselves as world figures. Kubrick made Dr. Strangelove (though its release was postponed to 1964 due to the Kennedy assassination). Losey, after a difficult period, often working under pseudonyms, had three films released: the dazzling Hammer thriller The Damned, the Franco-Italian psycho-drama Eve (both shown in versions re-edited by their producers) and the complex, fully achieved The Servant. Influenced by Marx and Brecht, The Servant was the first part of a trilogy scripted by Harold Pinter about class warfare, sexual conflict and struggles for power in 20th-century Britain, involving a whole society from the working class to the aristocracy.” And The Servant was followed by Accident (1967) and The Go-Between (1970).

For more on The Servant, see Alex Davidson (BFI), Tom Huddleston (Time Out, 5/5), Howard Male (Arts Desk), and John Patterson, once again in the Guardian, where Steve Rose talks with Sarah Miles and Wendy Craig about the film’s making.

“One of the key movies of the British new wave, Billy Liar began life in 1959 as a brilliant comic novel by Keith Waterhouse,” began the Philip French back in May on the occasion of another 50th anniversary restoration, “and in 1960 Waterhouse and his regular writing partner Willis Hall turned it into a play that Lindsay Anderson directed in the West End. It was filmed… under the direction of former actor and documentary maker John Schlesinger. Tom Courtenay (who took over the title role on stage from Albert Finney) is superb as the sad 19-year-old Billy Fisher, who escapes from his dreary lower-middle-class background and dead-end job as an undertaker’s clerk through his dreams of becoming a writer, his habitual lying, and his fantasies about being a hero in the imaginary country of Ambrosia.”

Writing for Electric Sheep, Paul Huckerby argues that “what makes Billy Liar a masterpiece of British Cinema is that it is not a classic Bildungsroman—a ‘how I became a writer/artist/filmmaker story’—but a tragedy. It is the story of a flawed character striving to better himself, doomed to failure and to retreat into his imagination. It is also a painfully funny comedy.” Graham Rickson, writing at the Arts Desk, agrees: “Watching the film again after several years, it’s the bleakness which hits home. There are laughs, but the overall tone is so sombre, so downbeat; this is a story about restricted ambition, narrowness of outlook and missed opportunities. Without Waterhouse’s wry humor, Billy Liar would be an unpleasant, grubby tale about an unlikely serial philanderer.”

In the Independent, John Walsh argues that Julie Christie, in her third screen role, and really only showing up for the last third of Billy Liar, “nearly steals the film…. She plays Liz, a local beauty of a kind never seen before…. She’s a girl who can’t be pinned down and won’t get stuck and, in 1963, this was a crazily unconventional position. Schlesinger celebrates it in a justly famous tracking shot, in which a long-lens camera watches Liz walking through her northern home-town, in a simple white shirt, skirt and jacket. We see her from inside shops, as she passes by, unselfconsciously swinging her handbag, smoking a cigarette, running her fingers along railings, her face smiling, grimacing at her own reflection, showing impatience at a pedestrian crossing. We watch her as an objectified consciousness: an emblem of independence.”

Before moving on from 1963, let’s take a few steps back. “Educated at Winchester and Oxford, lifelong socialist, closet gay, son of a Liberal prime minister, Anthony Asquith (1902-1968) is a currently undervalued filmmaker whose career began in the silent era when he studied American cinema in Hollywood and German expressionism in Berlin.” Once again, Philip French: “The British character in its various forms fascinated him, especially the middle classes, and he found an important collaborator in Terence Rattigan. Their association lasted from 1937 to the mid-1960s, resulting in numerous crucial works, including the wartime morale-booster The Way to the Stars [1945] and that masterpiece of stiff-upper-lip repression, The Browning Version [1951]. Just before the coming of sound Asquith made two silent classics, A Cottage on Dartmoor [1929] and Underground [1928] that put his rival Hitchcock into the shade in the way it absorbed foreign influences and experimented with new styles.”

For Graham Fuller, writing at the Arts Desk, Underground is “a light romantic-triangle melodrama that morphs unexpectedly into a cruel thriller and culminates in a vertiginous chase.”

“Poet, painter, designer, surrealist, Blakean social visionary, [Humphrey Jennings] brought all his gifts together as a documentary filmmaker,” writes Philip French in this week’s Observer. “He was, according to Lindsay Anderson, ‘the only real poet the British cinema has yet produced.’ The crucial second volume of his collected works included his wartime masterpieces, Listen to Britain (1942) and Fires Were Started (1943). Volume three rounds out the war with The True Story of Lili Marlene (1944), his odd recounting of how the German soldiers’ favorite ballad was taken up by the British squaddies, and A Diary for Timothy (1945), a film about the last year of the war and the prospects for the future, its delicate script written by E.M. Forster and beautifully read by Michael Redgrave.” Among the postwar films, “I think Family Portrait [1950]… ranks among his best work. ‘Family’ for him meant Britain, as it did for Orwell. Jennings’s posthumously published book on the history of the Industrial Revolution, Pandæmonium, is a key text that inspired Frank Cottrell Boyce and Danny Boyle’s 2012 Olympic Games opening ceremony.”

Martin Scorsese on the restoration of Richard III

“Who better to play the Bard’s most accomplished performer and manipulator than the most accomplished of all English actors?” asks Chris Cabin in Slant. “Donning a doozy of a puttied schnoz, a slightly exaggerated limp, and a boyish, midnight-black wig, Sir Laurence Olivier feels more at home in the eponymous role of his own adaptation of Richard III [1955] than he does in any of his other storied roles, holding and releasing the succulent prose with unerring confidence and clarity.” And it amounts to “the most fully captivating film adaptation of Shakespeare this side of Orson Welles‘s Othello.”

“The character of Richard is almost unique in the history of the movies (excepting certain modern horror films—Mary Harron’s American Psycho, for example) in being both an unredeemable villain and the protagonist of the story,” writes Amy Taubin for Criterion. “And more than a mere protagonist, he is the narrator and the confidant of the audience, providing us with titillating coming attractions, scabrous gossip, and mockingly reasonable accounts of his murderous schemes and acts. Unlike Macbeth, Richard is not a tragic figure, nor is he insane (at least not in Olivier’s interpretation). He does not murder for the betterment of the state or to make the throne more secure. He murders because he wants to be king, plain and simple.” This is “a one-man show—and also a rip-roaring action melodrama.”

More from Larry Peel (Ioncinema, 4.5/5); and Sam Smith‘s posted a few notes on his packaging design.

Michael Smith: “Newly released on Blu-ray from Lionsgate UK—meaning anyone living outside of Europe needs to have a multi-region Blu-ray player to enjoy it—is a newly restored version of Hammer Studios’ original 1958 production of Terence Fisher’s Dracula (also known to ugly Americans as Horror of Dracula). While I am by no means a Hammer expert, I do love a good horror movie as well as a good restoration job; this release happily combines both of those things in a high-quality package that probably deserves to be called the definitive home video presentation of Fisher’s masterpiece.”

“Viewed today on Blu-ray, [Richard] Lester’s use of color, collaborating with cinematographer David Watkin, might be Help!‘s [1965] most impressive achievement,” suggests C. Jerry Kutner at Bright Lights. “The Beatles were often compared to the four Marx Brothers…. However, Lester’s principal cinematic influences date even further back—to the silent era—not only the frequent use of title cards (‘The Exciting Adventure of Paul on The Floor’), but the visual humor of Buster Keaton, and the narrative proto-surrealism of French serial master, Louis Feuillade. Help!‘s plot device—rival criminal gangs pursuing a common object—recalls Feuillade serials like Les Vampires (1915) and Judex (1916).”

Budd Wilkins in Slant: “The shadow of Stanley Kubrick’s languorous historical satire Barry Lyndon [1975] looms large over Ridley Scott’s The Duellists [1977], a visually stunning adaptation of a lesser-known Joseph Conrad story about an ongoing duel between two French Hussar officers that spans the entire Napoleonic period (roughly 1800-1816)…. An obsessively detailed chronicle of obsession, The Duellists gets a sumptuous Blu-ray transfer from Shout! Factory, along with a solid new supplement, as well as some choice carryovers from the earlier DVD, even though there are one or two lamentable absences here.”

Criterion finds the beginning of Leigh’s new audio commentary track

“just too charming not to share”

“What soured Mike Leigh on Life Is Sweet?” wonders the Chicago Reader‘s J.R. Jones. “Earlier this year the British writer-director recorded a commentary for the Criterion Collection DVD of his 1990 drama, and at the very end, as the credits are about to roll, he admits that it’s his least favorite of the films he’s made. Leigh doesn’t explain, and earlier in the commentary he seems quite proud of, even moved by, certain moments. I suppose that’s the luxury of being Britain’s greatest living filmmaker: when you’ve got a track record that includes Secrets & Lies (1996), Topsy-Turvy (1999), All or Nothing (2002), Vera Drake (2004), and Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), you can afford to be picky. Life Is Sweet may be a minor film for Leigh, more loosely plotted even than some of his early TV movies for the BBC, but by any other measure it’s a wonder, with unforgettable characters and a distinctive mix of comedy and real sorrow.”

“In the high-spirited High Hopes [1988], he had skewered the pieties of nostalgic socialists and self-satisfied capitalists alike,” writes David Sterritt for Criterion; “in Life Is Sweet, he integrated knockabout comedy, sardonic dialogue, and nuanced sociological observation into his most sophisticated achievement yet.”

At Film.com, Calum Marsh compares Life Is Sweet with Naked (1993): “At first blush the two films seem like clear inversions of one another: where Naked feels thoroughly caustic and grim, a cynical reflection of and battle-cry against Thatcherism and social decay, Life Is Sweet looks markedly brighter, the harshness of its world more muted, its ending suggesting hope where Naked dashes it completely. The films even have opposite color palettes, with the sunny afternoon pastels of Life Is Sweet traded out in Naked for bruise-like blacks and blues…. But it seems obvious now, more than twenty years after its initial release, that Life Is Sweet is every bit as pained and angry as Naked—it’s just about characters less able or willing to articulate that anger.”

And they are, as sketched by Max Winter at RogerEbert.com: “Andy (Jim Broadbent) is one of the head chefs for a caterer. His wife Wendy (Alison Steadman) divides her time between teaching dance classes, waitressing and what she views as her homemaking duties. One of the family’s daughters, Nicola (Jane Horrocks), who is very troubled, has a boyfriend and then loses him. Family friend Aubrey (Timothy Spall) tries to open a restaurant, which fails. Another friend, Patsy (Stephen Rea) persuades Andy to buy a sandwich van, which goes nowhere. Life continues. All of these events are both important and utterly unimportant in this story of a family’s seesawing between function and dysfunction.”

Bringing us full circle, Sam Adams, writing at the AV Club, finds that “there’s a sense in which Leigh is playing rope-a-dope with the kitchen-sink genre, lulling the audience with familiar trappings while he lines up the next big punch. Rachel Portman’s score mixes the joyful lilt of an oboe with a theremin’s unearthly wail and the tingle of a bouzouki—not exactly the soundtrack you’d find attached to a contemporary movie by Ken Loach or Alan Clarke. The hybrid creates a new genre: magic social realism.”

Related entry. “The Hitchcock 9-Plus.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.