“For the first time in the UK,” writes Phelim O’Neill in the Guardian, “a film is being released across all formats–cinema, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD and broadcast TV–on the same day.” And that day is today. “They will arrive in one burst rather than being staggered across several months in the traditional manner. (There’s even a limited edition VHS release being planned, so no one feels left out of the fun.) It may seem revolutionary, maybe even foolhardy: but this is an experiment in distribution designed not only to turn the release into an event, but also to finally acknowledge that our viewing habits–how we consumers consume movies–have changed drastically over the past decade. You can bet the film industry will be watching the results very closely.” It’ll help, of course, if the film’s a good one—and, going by the reviews that’ve appeared so far, the risk may well pay off.

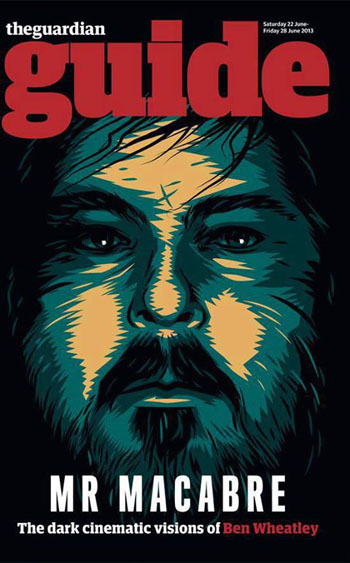

“A strikingly original historical thriller spiced with occult mysticism and mind-warping hallucinations, British director Ben Wheatley’s fourth feature has all the midnight-movie intensity of a future cult classic,” begins Stephen Dalton in the Hollywood Reporter. “Specializing in low-budget hybrids of dark comedy and bone-chilling horror, Wheatley so far seems to be following a career path akin to Peter Jackson or Sam Raimi. A potential mainstream crossover lies ahead in his next project, Freakshift, an effects-driven monster movie shooting in the U.S. Meanwhile, A Field in England is his most boldly experimental work yet, a black-and-white psychedelic bloodbath set during the English Civil War of the mid-17th century. It was shot in just 12 days on a super-lean budget of £300,000, comfortably below half a million U.S. dollars.”

“Wheatley’s new film is grisly and visceral, an occult, monochrome-psychedelic breakdown,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “A group of deserters, starving and staggering across country in the entirely delusional hope of an ‘alehouse’ over the next hill, fall under the sinister control of O’Neil, a necromancer and practitioner of the forbidden arts, played by Michael Smiley. O’Neil enforces his sadistic will especially on the cringing scholar Whitehead (Reece Shearsmith), who is required to help him locate a buried cache of gold somewhere in the field. Amid the carnage of war, the men’s fear of death, pain and the non-existence of God creates the conditions for general hysteria that is ignited by eating the variously shaped mushrooms sprouting in the soil…. What a unique filmmaker Wheatley is becoming.”

And the Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin reminds us that “Wheatley is the busy director who in the last four years has brought us Down Terrace, Kill List and Sightseers: pictures so infested with ideas and riddled with self-assurance that they can single-handedly restore your faith in the future of British filmmaking. But they also make you cherish its past, and the influence of directors from Mike Leigh to Ken Russell pop up everywhere in Wheatley’s brief back catalogue…. A Field in England claims kinship with the rural horror films that flourished in Britain in the Sixies and Seventies; doomy, sexy frolics with titles like Witchfinder General and The Blood on Satan’s Claw…. But when it comes to business, Wheatley’s film cleaves to genre rules less often than it chops clean through them.”

For Jessica Kiang, writing at the Playlist, A Field in England suggests a “mashup of the melancholic aesthetic of Ingmar Bergman, the comedic sensibility of Mel Brooks and the tonal uneasiness of Lars von Trier… by way of Samuel Beckett, The Wicker Man and Sergio Leone…. If prior films have positioned Wheatley at the rickety bridge between genre and indie/arthouse filmmaking, then A Field in England is him straying right out onto the middle of it in a high gale and jumping up and down. Some viewers will no doubt tire of trying to hang on in there but those who manage to do so have a bracing, sometimes exhilaratingly bonkers experience in store.”

Alternative trailer: “Designed, Edited & Manipulated by Julian House at Intro-Partnership.”

“It is defiantly strange, but mesmerizing and intriguing at the same time,” writes Screen‘s Mark Adams. “The script by Amy Jump (Wheatley’s wife and regular collaborator) is rich, earthy and vibrant, and beautifully complemented by Laurie Rose’s lustrous black-and-white cinematography.”

But at Little White Lies, David Jenkins “really, really didn’t get on with Wheatley’s wacky, indulgent latest… Not only is A Field In England a film which defies explanation, it wantonly repels it. It’s less a film, it’s a filmed art school stag do…. Props must go to Wheatley for producing something so stubbornly unclassifiable, but there is simply no fun in consuming a film which revels in its own pointlessness.”

“This is a film built on sensation, misdirection and randomness,” argues Time Out‘s Tom Huddleston. “The result can be maddeningly obtuse, but it’s also breathtakingly lovely and genuinely unsettling. As the historical setting suggests, early ’70s folk-horror is a key influence. But so are the experimental films of Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage: towards the end, there’s a ten-minute sequence of pure psychedelic freefall and freakout which is one of the most captivating, hypnotic and beautiful things you’ll ever see on a cinema screen.”

“Variants on its multi-platform release have been tried before,” notes Nick Hasted at the Arts Desk. “What’s particular to Wheatley’s sure-footed, industrious and brilliant career so far is the ambitious positive thinking of the assault. Debut Down Terrace was made on faith in a Brighton friend’s house; Kill List and Sightseers followed through its breach in the industry’s defences with breathtaking speed. A Field in England was shot in 12 days between other projects, but grows in the mind as much more than a stopgap.”

It’d been growing in Wheatley’s mind for around 20 years. As he tells Alex Godfrey in the Guardian, he’d always been interested in the period: “The Puritans were trying to iron paganism and magic out of Catholicism. Splitting up and melding ideas. There are two really important periods in British history where we actually made a difference to the world—the civil war and the industrial revolution—and I think at that moment in England, anything could have happened. Everyone was starving, and they were basically killing God, because they were killing the king, God’s representative; they were writing their own rules. As O’Neil says, ‘This country’s at the edge of something, it could become anything.’ That’s what got us excited about the period. It’s a time when people were thinking hard and radically.”

Back at Little White Lies, Paul Weedon “considers the ever-shifting paradigm of film distribution.” For the BFI, Sam Wigley lists “10 great films set in the 17th century.”

Updates: “A Field in England spins a single moment in history so that it becomes the centrifuge of all history,” writes Nigel Andrews in the Financial Times. “It is a ridiculously bold, imaginative movie. Its whirring dynamic is as likely to fling audiences outwards in fright or flight as to have them pinned, thrilled and gravity-defiant, to its fun-fair walls. I nominate it as a cult classic right now, with the ‘cult’ disposable in the future at the first stage of canonic lift-off.”

“This is not another British project made to formulaic guidelines,” writes Geoffrey Macnab in the Independent. “Even the bloody final battle—which seems a bit like a spaghetti Western shootout transplanted to 17th-century rural England—confounds our expectations.”

Mat Colegate interviews Wheatley for the Quietus.

Update, 7/6: “One possible reading,” suggests Philip Kemp in Sight & Sound, “supported by certain lines of dialogue—’There are only shadows here,’ ‘You are nothing more than an envelope’—could be that some or all of the characters are already dead, killed on the battlefield. Another, that Whitehead hallucinates the whole thing after stuffing his face with magic mushrooms and seeing a huge roiling black planet about to engulf the Earth. But for all its ominous portents, there are hints that the film isn’t taking itself 100 per cent seriously; as ever with Wheatley, black humor lurks in the corners.”

Update, 7/7: The Guardian‘s Catherine Shoard finds Field to be “almost unbearable.”

Update, 7/8: Cineuropa interviews Wheatley (10’35”).

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.