Aleksei German, “a Russian film director best known for his works chronicling the Stalinist era in the Soviet Union, died in Moscow on Thursday,” reports the AP. “He was 74.”

German’s filmography (the “G” is pronounced hard, by the way) is small but huge, which is to say, he made only a handful of films, but, as Anton Dolin wrote in Film Comment last year as a retrospective was touring the States, “to many Russian critics, cinephiles, and viewers German is their national cinema’s foremost figure after Tarkovsky. Others insist that, in fact, he is more important and more original. Still others have never heard of him or confuse him with his namesake and son Alexei German Jr. (who’s been considerably luckier: at age 35 he’s already made three films and received three awards in Venice)…. There’s a saying: ‘To solve a difficult problem, you need a Chinese. To solve an impossible one, a Russian.’ They must have been thinking of German. Besides, how many other geniuses have managed to displease the Soviet censors, the post-Soviet commercial system, and the connoisseurs of Cannes?”

Maxim Pozdorovkin in MUBI’s Notebook last March: “Starting with his first solo directed feature, Trial on the Road (1971), studio heads and their like have all told German, ‘these brilliant moments do not add up to a film.’ The implicit point being, as German himself has said in interviews, that the officials never saw him as a dissident but more as a great assistant director, someone excellent with backdrops, B-roll, and secondary characters. Soviet cinema’s New Wave began with Marlen Khutsiev’s I Was 20 Years Old (1961) and dissipated around Brezhnev’s death in 1982. The era launched the careers of three major filmmakers: Andrei Tarkovsky, Kira Muratova, and Aleksei German. Of the troika, Muratova has been the most productive, Tarkovsky, the most emblematic, and German, Teutonic last name aside, has been the most Russian.”

“The production of his second film Twenty Days without War was less problematic,” noted Tony Wood in the New Left Review in 2001. “Made in 1976, it was released after only six months’ delay although again, it looks aslant at a crucial Soviet story: the siege of Stalingrad. German has described it as ‘an anti-romantic melodrama’ with ‘anti-beautiful’ heroes. The middle-aged Lopatin has twenty days’ leave from the battle and spends it in Tashkent. He visits his ex-wife, signs divorce papers, meets up with friends and becomes involved with another woman; then his leave is curtailed and he is sent back to fight. We see nothing of Stalingrad itself. As is frequently the case in German’s work, plot is minimal, the emphasis instead being on the portrayal of a mood. Perhaps more importantly, neither characters nor events are typically heroic. Lopatin is part of an army that has begun to turn the tide, yet throughout the film he looks dog-tired, and smiles only briefly flit across his face.”

In May 2009, Kevin B. Lee posted a mammoth roundup on My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1983) prefaced with his own observations:

Upon its 1982 release, it garnered equal parts acclaim and controversy for its frank depiction of 1930s small town Soviet life, with comrades threatening to report each other and casual references to drugs, prostitution and secret police backroom brutality. The film was heralded as the greatest Soviet film of all time, beating out the likes of Tarkovsky and Eisenstein; today it’s largely unremarked outside of (and even among) Russian film circles.

The narrative is an extended series of unfiltered incidents of the past strung together in a loosely linear sequence. Despite being mostly shot in black and white and sepia, the film is alive with an unruly, uncentered and unprocessed feel of communal activity. Alexsei German orchestrates this action with masterful long takes and tracking shots. But unlike the employment of this technique by Tarkovsky or Béla Tarr, German doesn’t so much connect images along a meditative stream with his more roughhewn, often handheld camerawork as clash them in an animated clatter of incongruity, something resembling collage art.

Writing for Artforum last year, Tony Pipolo noted that “the stylistic shift from his first four films to Khrustalyov, My Car! is dazzling—like stumbling upon Fellini’s wildly dreamlike 8½ (1963) after having seen his Neorealist films.” It’s a “phantasmagoric satire, conjuring a bizarre, nightmarish Moscow in 1953.” In a 1999 piece for Film Comment, J. Hoberman wrote that the “narrative is not difficult to follow but the succession of events is dizzying. The hallucinated environment supersedes all but the most grossly physical events, Khrustalyov‘s extraordinarily crisp black-and-white images are married to a soundtrack as clamorous as the mise en scène is cluttered…. I asked German if Khrustalyov was about present-day Russia. ‘Of course,’ he replied, adding that ‘maybe things are simpler now—they just shoot you…. We didn’t really want to depict 1953, we wanted to show what Russians are like.'”

For more on German, see last year’s Notebook roundup and Ronald Holloway‘s 1988 interview for Kinoeye.

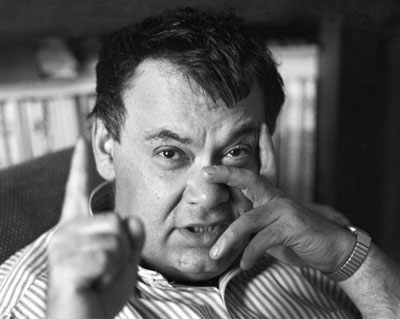

Updates: Glenn Kenny‘s posted that image to the right “from the magnificent, endlessly upsetting 1998 Khrustalyov, My Car, which may well be the last completed film by this now-departed master…. A cataclysmic loss, to put it mildly.”

Blogging for the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Nicholas Kemp notes that “Guerman’s son, also a filmmaker, wrote early this morning: ‘My father has lived his life in dignity. He never betrayed his ideals; never sold out; never bartered himself in exchange for vanity. I believe he left for a better world.’ Tragically, Guerman’s passing comes just before the completion of his decades-in-the-making new film, an adaptation of Arkady and Boris Sturgatsky’s celebrated 1964 sci-fi novel Hard to Be a God. The film is said to be in post-production and could premiere later this year.”

Update, 2/22: At Artinfo, Graham Fuller notes that German’s son has written on his blog that “his father’s swansong is nearly complete: ‘The film It Is Hard to Be a God is in effect finished. All that remains is the audio dubbing. Everything else is finished. It will be completed in the foreseeable future. The making of the film was long and painful… It was made without government money.’ AP says that the film ‘has generated a lot of public expectations and intense discussion, with some seeing it as a stinging satire on President Vladimir Putin’s Russia, full of grim predictions for the future.'”

Updates, 2/23: Wikipedia refers to Hard to Be a God as History of the Arkanar Massacre—and Constant Shallowness Leads to Evil has posted a batch of stills. A documentary about the film’s making was screened at last year’s Visions du Réel.

Meantime, do see Giuliano‘s remembrance noted in a comment below, and, for those who read French, Jean-Michel Frodon‘s as well.

Update, 2/24: “Aleksei Yuryevich German was born in Leningrad on July 20, 1938, the son of Yuri German, a Soviet writer on whose stories Trial of the Road and My Friend Ivan Lapshin are based,” notes Sophia Kishkovsy in her obit for the New York Times. “Mr. German graduated from the Leningrad Theater Institute in 1960 and began working in 1964 as an assistant director at the Lenfilm studio. He battled in the post-Soviet era to save the studio from collapse, ‘at the cost of his health,’ his son wrote in his blog. In 2011, Mr. German and the director Aleksandr Sokurov wrote a letter to President Vladimir V. Putin entreating him to save the studio.”

Update, 2/26: “Khrustalyov, My Car!, the only one of his works that was not banned, provoked a mass walkout by critics at the 1998 Cannes film festival,” notes Ronald Bergan in his obit for the Guardian. “According to the Hollywood Reporter, the 150-minute film was ‘incomprehensible for long stretches and unforgivably unfunny in the endless scenes of manic visual satire.’ Martin Scorsese, who was president of the Cannes jury, remarked that German’s film obviously deserved the Palme d’Or, but he wasn’t able to convince his fellow jurors because he didn’t really understand it. Since then, many critics, initially confused by the opaque narrative and overwhelmed by its black humour and nightmarish vision of Russia during the last days of Stalin, have acclaimed the film.”

Update, 3/3: A passage from Ian Christie‘s remembrance for openDemocracy, “The Alexei German I knew”:

My first encounter came in 1984, when the Soviet Filmmakers Union invited me to assemble a delegation of British ‘independent’ filmmakers, so that they could see at first hand the kind of avant-garde work that never reached official platforms such as the Moscow Film Festival. Our little group included the filmmakers Sally Potter and Derek Jarman, neither as well known as they would become, along with Ed Bennett, Peter Wollen and Peter Sainsbury from the British Film Institute Production Board. Among the films the Union offered to show us was German’s Twenty Days Without War, which had been made in 1977 but never seen abroad. Jarman, who was shooting clandestinely what would become his Imagining October, was deeply impressed by this understated, melancholic reflection on the heightened realities of wartime life on the home front. The world-weary war reporter on leave from Stalingrad, we learned was played by Yuri Nikulin, an ex-clown, who was also one of the most popular of screen comedians. His love interest was played by an equally popular actor and singer Ludmilla Gurchenko; but oblivious to this casting against reputation, we only knew we had seen something of extraordinary integrity in the burnished black-and-white that German always used.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.