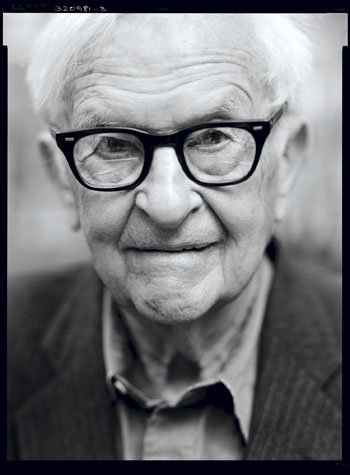

In the entry I posted just minutes ago, I noted that a new documentary co-directed by Albert Maysles will see its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival next month and that a new restoration of Grey Gardens (1976), which Justin Stewart calls a “horrifying classic” in the L this week, begins its week-long run at Film Forum today. All this makes the breaking news that Maysles has died at the age of 88 all the more rattling. The pioneering documentarian was working right up to the end.

The Guardian‘s Andrew Pulver: “Together with his brother David (who died in 1987, aged 54), Maysles made a string of documentaries from the early 60s onwards—initially specializing in entertainment, such as with their 1964 film about the Beatles’ first trip to the US—that would radically influence the entire documentary movement. They were regarded as leaders in the field of ‘direct cinema,’ which prized intimate, unselfconscious observation that was made possible by lightweight cameras and sound recorders. French new wave director Jean-Luc Godard called Maysles ‘the best American cameraman.'”

Anita Gates: “Explaining why his films did not include interviews with their subjects, Mr. Maysles (pronounced MAY-zuls) told a writer for the New York Times in 1994: ‘Making a film isn’t finding the answer to a question; it’s trying to capture life as it is.’ Although the Maysles brothers had made several well-regarded documentaries in the 1960s, it was Gimme Shelter (1970), about the Rolling Stones’ 1969 American tour, that brought their work widespread attention. The film included a scene of a fan being stabbed to death at the group’s concert in Altamont, Calif., and the critical admiration for the film was at least partly countered by concerns about exploitation of that violence. Similar concerns were expressed about Grey Gardens (1975), a double portrait of Edith Bouvier and her daughter, Edith Bouvier Beale, both cousins of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who lived in squalor and with some obvious mental confusion in what had once been a grand East Hampton house. But the film captured and held the public’s attention for decades.”

“Gimme Shelter takes one of the defining moments of the 1960s,” wrote Toby Miller for Criterion in 2001, “and helps us see what all the fuss of youth rebellion was all about. Given their prowess in examining the counterculture of that tumultuous decade, it’s doubly impressive that their exquisite Salesman (1969) so skillfully details the ‘other’ ’60s, the world of ‘ordinary’ people animated by making do with everyday life rather than preoccupations with Vietnam, drugs, and social change. These are the door-to-door Bible salesmen and their customers, and they occupy a world of starched white shirts, dark ties, pork-pie hats, and morning cigarette coughs—a world far removed from tie-dyes, beads, long hair, and pot highs.”

“Admittedly, the Maysles straddled a line between artistic license and non-fiction narrative,” writes Duane Byrge in the Hollywood Reporter. “‘Al and Dave often argue that all they’re doing is filming what’s there. The detail is comment: fingers scratching, soft focusing. A filmmaker is always making comments,’ Haskell Wexler opined in a Village Voice article on their career.”

Anna Silman for Salon: “Among Maysles’s many achievements, he was nominated for a documentary short Oscar for Christo’s Valley Curtain in 1974, won two Emmys, and received the National Medal of Arts from Obama last July.” Just the other day, Landon Palmer compiled “6 Filmmaking Tips from Albert Maysles” for Film School Rejects. The Telegraph has just re-posted Horatia Harrod‘s 2008 interview. Our own Jonathan Marlow had a good long talk with him in 2013.

Updates: “Born in Boston, Albert Maysles began his career working in a mental hospital and teaching psychology at Boston University,” notes Keith Phipps at the Dissolve. “In 1955, he seized an opportunity to merge his expertise with a lifelong interest in photography by talking his way into an assignment making the film Psychiatry in Russia for CBS. Asked by Interview magazine, years later, if he saw this as a natural progression, Maysles replied: ‘It seemed that way to me, yeah. The psychologist can’t counter things with a point of view, but always has to be open to whatever is really going on.’ … When I interviewed Albert Maysles in 2000, I asked him the influence of the approach he pioneered. He replied: ‘I think it’s been a trend over the years for Hollywood not to give up its aesthetic of grandeur and expense, but to make things look more realistic. … But still, you don’t get the realism on screen. It’s only when it’s really real that you get that.'”

Big Edie and Little Edie “could have come from the 19th century,” suggests the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. “They were stranger than fiction. Tennessee Williams could have scripted Big Edie and Little Edie—but it would have been too operatic. Gore Vidal might have done so—but he would have been too caustic. Albert Maysles, with his brother David, was perfect: reticent, cool, gentle, and yet shrewd. In Grey Gardens, Maysles created a great American work of art.”

Filmmaker‘s Scott Macaulay notes that Maysles has yet another documentary set for release, Iris, about interior designer Iris Apfel. “In addition to his work directing, Maysles was a generous supporter of young filmmakers and the documentary form in general, having formed Harlem’s Maysles Documentary Center in 2005.”

“Maysles was also a cinematographer behind iconic music documentaries such as 1968’s Monterey Pop and 1977’s The Grateful Dead Movie,” adds Jason Newman at Rolling Stone. “When influential film magazine Sight & Sound released their inaugural list of the Greatest Documentaries of All Time, Grey Gardens was listed at Number Nine. “Imagine if John Waters shot a script by Tennessee Williams and it was broadcast in a TV slot usually reserved for The Hoarder Next Door or How Clean Is Your House?” the list’s authors wrote. (Salesman and Gimme Shelter also appeared on the list.)”

“Maysles’s style is often imitated by filmmakers both inside and outside of the documentary form,” writes Max O’Connell at Criticwire, “but his skill as an observer of human behavior is close to unparalleled. Any director can step back and watch things happen, but it takes a master to know where to look when things happen. In Gimme Shelter, the climactic scene at Altamont shows a filmmaker who knows when to look at the disaster brewing and when to turn to the men at the center and see how they’re taking it in. Moreover, few filmmakers can sustain a constant mood of doom (Gimme Shelter), desperation (Salesman) or loss (Grey Gardens) like Maysles can without seeming like they’re manipulating events.”

“David carried the shotgun mic and Nagra recorder, Albert carried the camera, and together they made movies that became cultural touchstones and helped define the language and scope of non-fiction film.” Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club: “The late 1950s and early 1960s were a time of rapid change for non-fiction film… Along with Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker—both of whom worked with Albert Maysles as cameraman on Robert Drew’s groundbreaking Primary (1960)—the Maysleses came to define direct cinema, the American answer to cinema vérité.”

“We saw things through his lens that we will never forget, and he was a filmmaker up until the end.” Criterion‘s posted a remembrance and a photo gallery.

Adam Schartoff spoke with Maysles on Filmwax Radio in December 2013.

And in 2000, Ray Pride spoke with him on the occasion of a new restoration of Gimme Shelter:

“Did I tell you the story of my experience with Fidel?” the generous, avuncular raconteur begins. Yes, but tell us again. “In 1960, I spent a lot of time with Fidel and with Che, also. I was making a film that ended up being called Yanqui No! One day, Fidel mentioned that he was going to the Chinese Embassy for a party, did I want to come along? I said, ‘Sure.’ So I’m with him at the Chinese Embassy, standing shoulder to shoulder, I don’t have my camera because I couldn’t just walk in with it on my shoulder, I would need someone to do sound. A messenger comes rushing in, hands a telegram. He opens it. As he’s opening it, reading it, knowing that I don’t speak or read Spanish, he turns to me, and says, ‘Shall I translate it for you.’ I say, ‘Please do.’ Just inches away from me, he tells me, ‘The State Department has just broken off relations with Cuba!’”

Maysles smiles. “I have some plans to go back to Cuba. This time, I’ll have my little video camera.” He holds up his palm to show the camera’s scale. “If I’m at the Chinese Embassy, the Romanian embassy, wherever it is, I’ll have that little camera ready when he reads the telegram which he’ll translate, saying, ‘The American State Department has restored relations with Cuba’! I missed the first one because of the movie camera. I’ll get the second one because of my video camera!”

In 2009, Catherine Grant put together an outstanding collection of scholarly resources on Albert Maysles.

Updates, 3/7: The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody met Maysles in “late 1984 or early 1985”: “Al Maysles handled his camera with a fluid yet forthright, light yet ardent touch—from the start, he was a sort of Impressionist portraitist: he wanted to capture the most evanescent of appearances, because he saw that they contained and revealed the deepest of emotions and motives. He let his own eye and hand yield to his own impulses and inclinations because he wasn’t, he knew, separate from the events that he filmed or isolated from the participants whom he filmed— rather, he was inextricably connected to them both.”

“As a Jewish boy growing up in Boston in the 1930s, he was a frequent target of anti-Semitic bullies, and was diagnosed as a child with a learning disability that he would later credit with helping him develop his ability as a deep listener, a skill that would inform his work throughout his career,” writes Rachel Shukert for Tablet. “Indeed, no matter who Maysles was shooting, you can tell that his is a presence in which they feel safe, in which they—perhaps finally—feel understood and seen. It’s this quality, profoundly empathic yet free from sentiment, for which Maysles will just be most remembered. Well, that and his iconic glasses, which really were a revolutionary costume for the day.”

“I worked in production with Albert at Maysles Films for three years at the turn of the millennium, a time when his passion for the possibilities of nonfiction filmmaking was reignited by another technological revolution: that of the digital camera.” Charles Loxton for Slate: “Throughout his career, Albert remained a bit of a techie. Always adapting his gear for the field, he once glued a small circular mirror to an elbowed metal rod, which he then secured with electrician’s tape to the bottom of his old Bach Auricon so he could see what was going on behind him while he was rolling.”

“In 2009, almost six years ago, Albert Maysles came to our apartment to shoot footage of my two boys, Ben and Sam, talking to each other,” writes S. Jhoanna Robledo for Vulture. “Two years later—two years!—he returned to shoot again…. I don’t know what became of the film about children. In 2011, he told Paper magazine that what interested him was that ‘kids come up with the most beautiful ideas and can express them so uniquely.’ I’m just glad he had the interest to keep going.”

“Maysles believed in the documentary community and took it upon himself to become a mentor,” writes Karen Kemmerle for Tribeca. “He recently joined up-and-coming filmmakers Nelson Walker, Lynn True, David Usui and Ben Wu for the anthology documentary, In Transit… This poignant observational film follows a group of train passengers as they ride and interact on The Empire Builder, which runs from Chicago to Seattle.”

Mekado Murphy has collected clips from the docs for the New York Times.

Updates, 3/8: “Maysles, who shot all his own pictures, always worked as part of a collective, often sharing the director’s credit with his soundman and co-producer brother, editors and another cameraman,” writes Ronald Bergan for the Guardian. “Later in life he concentrated on portraits of classical music performers—Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic (1985), Ozawa (1985), about the conductor Seiji Ozawa, Jessye Norman Sings Carmen (1989)—as well as environmental art, with Christo in Paris (1990). He also dealt for the first time with social issues, co-directing with Deborah Dickson and Susan Frömke, Abortion: Desperate Choices (1992), which traces the history of abortion in the US, and Lalee’s Kin: The Legacy of Cotton (2001), an account of an African-American family in the Mississippi Delta trying to cope with poverty. By letting people speak for themselves, the directors avoided sentimentality.”

Matt Zoller Seitz has posted his 2002 profile at RogerEbert.com.

Update, 3/9: The Telegraph has posted a 2008 appreciation from Martin Scorsese: “I once had a job as Al’s assistant, and I had to ‘aim’ or ‘focus’ lights as needed. It was a tough job—I had to follow, even anticipate, his every move, and I could see how attuned he was to the world before his camera. It was like watching a master paint. Al truly does have the eye of a poet. Which is ultimately what makes the camera disappear, and give way to life.”

Updates, 3/12: “Few figures in the history of cinema have meant as much to the way we make and watch movies,” writes documentary filmmaker Robert Greene in a lovely remembrance for Sight & Sound.

At Flavorwire, producer and editor Eric Pfriender has a few stories to tell about working with Maysles.

Adam Bhala Lough for Filmmaker: “Somehow I had ended up a houseguest of perhaps the greatest documentary filmmaker of our time, and now I was scrambling eggs in his kitchen and watching him read the paper.”

The Austin Chronicle‘s Marjorie Baumgarten points us Anne S. Lewis’s interviews, the first conducted in 2000, the second in 2002.

Update, 3/17: From D.A. Pennebaker: “My friendship with Al was forged during four months of filming together, just the two of us, in Russia in 1959. When he got a camera against his eye, he was one of the world’s great watchers, and I knew we would always be filmmaking companions.”

Updates, 3/21: “I was waiting in line at Union Station to board the Amtrak train from Chicago to Whitefish, Montana, where I was heading to go skiing with my brother-in-law, in mid-December 2013, when I had a once-in-a-lifetime encounter with a true legend.” Josh Golden for RogerEbert.com.

At the Dissolve, Nathan Rabin revisits Gimme Shelter, which “has the strange double infamy of being at once one of the finest concert films ever made, a movie that captures The Rolling Stones and earlier act Tina Turner at their peak, as well as a moratorium for the dreams and hopes of the 1960s.”

Update, 3/24: At Movie Morlocks, Susan Doll presents a primer on Maysles and cinema verite.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.