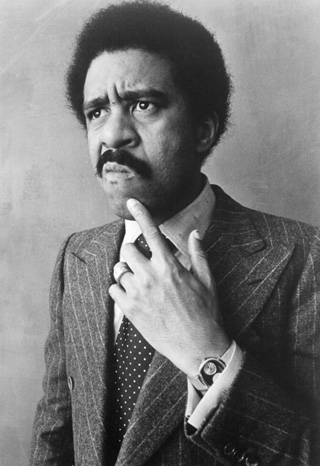

The other day, I mentioned Colin Beckett‘s piece in the new issue of the Brooklyn Rail. But only mentioned it. Here’s how it opens: “There are a few things that everybody knows about Richard Pryor: that he lit himself on fire in a suicide attempt while freebasing cocaine; that his stand-up revolutionized the form and altered the terms of American race relations; and that the movies he made were, for the most part, very bad. A Pryor Engagement, BAMCinématek’s two-week, 18-film retrospective quarrels with this latter proposition. Drawing on the beloved concert films, Pryor’s few exceptional turns as an actor, a handful of movies in which he appears only briefly, and enough of the total dogs to keep things fair, the series makes a limited case for the virtues of Pryor’s filmography.”

BAMcinématek’s own Andrew Chan: “With a style that encompassed autobiography, social commentary, and imaginative flights of storytelling and mimicry, Pryor reset the political and emotional parameters of American comedy in such a radical way that when the John F. Kennedy Center for Performing Arts established the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in the late 1990s, he was an obvious choice to be its first recipient.”

“In the decade that included his greatest achievement, the seminal 1979 stand-up concert film Richard Pryor: Live! In Concert, Pryor delivered many superb, committed, often brief performances hidden in movies that were mediocre or worse,” grants Jason Zinoman in the New York Times. “One of the good things about bad movies from that era, particularly the low-budget ones, is that they often didn’t get in the way of comic performers, as they did in later years. Their slower pace allowed for more improvisation and spontaneity. Pryor, who appeared in about 20 movies around that time, was drawn to dramatic roles. He’s a gentle, doomed piano player in the Billie Holiday biopic Lady Sings the Blues, and imbues the wizard in The Wiz with a pathos and terror at odds with that frenetic musical.”

“He inhabited the experiences of working class urban and exurban mid-to-late 20th century blacks, finding cathartic waves of laughter in the sex lives, addictions, familial relationship, and delicately concealed anger of the kind of people he almost never got to play on movie screens,” writes Brandon Harris at the New Inquiry. “Black American movie stardom existed before Richard Pryor, flourished even, but through the lens of his arc from ace comic and blaxploitation bit player extraordinaire to the only black movie star of significance for the first third of the 80’s, we see the ways in which white America was only so ready for the coiled sadness and gallows humor that so many black filmmakers of his era would surely have offered him the chance to perform on the silver screen. He could be a movie star, but only on the market’s terms, which is another way of saying he could only be Gene Wilder’s straight man or, at his best, if just once, the spectre of the working man corrupted by the machinations of industry. His most lasting work will be his bold and singular comedy, but he’ll be most remembered for playing characters that were as disempowered as the black audiences without a Civil Rights Movement or a cinema to call their own.”

“A Pryor Engagement ends on February 21st with the two films Pryor directed,” notes Odie “Odienator” Henderson: Here and Now (1983) and Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life is Calling (1986). Henderson wrote about Jo Jo back in 2011, also at the House Next Door. Today, he adds: “It’s Pryor’s All That Jazz, a funny and ultimately devastating hash of a film. Pryor’s choices behind the camera (aided by John Alonzo), make me wish he’d directed other films. For all its narrative flaws, Jo Jo Dancer is visually arresting, with Pryor’s dual incarnation serving as both master of ceremony and dramatic actor. For one who, according to Bill Cosby, merged comedy and tragedy, painting the line between them ‘as thin as one could possibly paint it,’ this is a fine way to end a fascinating series.

Update, 2/10: In 1982, Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote a piece on Richard Pryor, and he’s now posted it with a forward, noting that he still considers it “one of my better pieces about comedy.”

Updates, 2/14: Miriam Bale on James B. Harris’s Some Call it Loving (1973): “Pryor’s appearance as the wino-philosopher best friend is brief. Yet it also somehow gets closer to the surreal, subversive pathos of Pryor’s brilliant standup performances than his later, negligible, middle-brow comedies.”

BAM’s Andrew Chan talks with Pryor’s widow, Jennifer Lee Pryor, about their relationship and his career.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.