[Editor’s note: Keyframe republishes this February, 2014, Jodie Mack story in conjunction with her appearance as a featured FIX filmmaker.]

It is not easy to make experimental films. Since the support system that exists for artisanal filmmakers is miniscule, if it exists at all, even the most motivated film and videomakers must balance their commitment to their art with a great many other demands. This means that it’s difficult for avant-garde media artists to work with the intensity that can potentially result in great advances and breakthroughs in one’s creative practice in a relatively brief amount of time. Many major film artists average one to two short films per year. While this can say as much about their individual working methods and level of concentration on a single work, I think it also points to the exigencies of life that require most artists to articulate their visions in the interstitial moments between other tasks—teaching, other day jobs, family life, what have you.

Jodie Mack is a relatively young filmmaker. She has emerged as a significant force on the experimental scene only in the last few years. She is a professor at Dartmouth, where she teaches filmmaking. Part of what is truly remarkable about Mack’s work is the sheer volume of high-quality films and web-based imagery she has produced in a relatively short time (around thirty films in eight years), including the recent karaoke-based featurette, Dusty Stacks of Mom: The Poster Project. In the midst of this flurry of activity, Mack has developed and refined a highly idiosyncratic approach to animated imagery. Her work builds on the legacy of such masters as Robert Breer, Lawrence Jordan, Janie Geiser, and Lewis Klahr, while at the same time locating a highly personal and humorous style of handmade formalism.

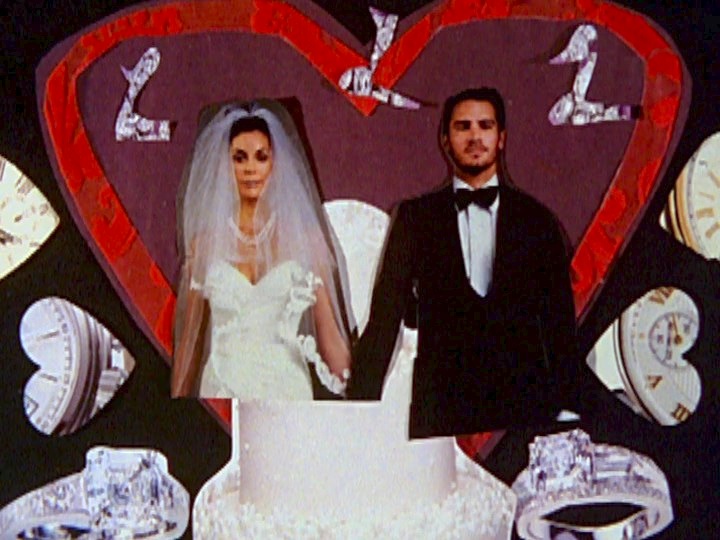

Mack’s high level of productivity is matched by the continued invention and exploration of her craft, and she shows no signs of slowing. In fact, by comparing two very different works of Mack’s, we can see the range of her expressive language. The relatively early Yard Work is Hard Work from 2008 is a prelude of sorts to her recent musical. One of her last works to deal with representational imagery, it is a thirty-minute, three-act musical addressing the commodification of love and romance. The first section features a female and a male voice singing to one another about their perfect love, and how they need to get married and live together. “Let [him/her] be someone with whom I can experience all the things I am not,” they sing, as the dating phase mutates into monogamy. Mack makes it clear, through her hackneyed magazine images from Cosmopolitan, Esquire, and various ads for luxury items, that these people are following a cultural script, even though their desires (and their loneliness) is very real.)

Once they buy a home, they run smack-dab into the middle of the housing crisis. They own a blue plaid home that sticks out among the cookie-cutter suburban ranch homes. It’s a way to express their quirky personalities, but as we know from HGTV, this originality will become a liability when it comes time to sell. (“This is labor-intensive / not to mention expensive.”) They also come to recognize that home ownership is a trap; the upkeep of a household takes so much time that they cannot do the things that they really want to do. Yard work is hard work. In time, they are up their eyeballs in debt. They can’t make their adjustable mortgage payments, and they discover that their TV and magazine-endorsed investment in the heteronormative American Dream has destroyed their nascent happiness, and their financial future. In a last-ditch effort to recoup some of their investment, the couple enters a contest to make their home “green.” They don’t win, but “we did make some improvements, that resulted in some money saving, and we both got better jobs.” In the end, the couple is declared “a work in progress.”

Yard Work is probably Mack’s most accessible film. In a way it is like a more overtly narrative Lewis Klahr film, and one that takes certain ideas from contemporary society (home renovation, bridal culture, the impact of the economy on average couples) and subjects them to a critical reading. It’s a slyly political work, partaking of the double-edged feminist irony we haven’t seen very much of since the 1980s and 90s, from artists like Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, and Martha Rosler.

In their own way, Mack’s more formalist animations also have a political edge. They can be viewed and appreciated as pure optical sensations. Mack’s senses of rhythm and pacing, as well as her careful articulations of color and shape, are masterful. Persian Pickles (2012), for example, finds Mack working with the possibilities of the Paisley shape. Using frame animation of different swaths of Oriental rugs (or curtains, or Paisley material), she cuts between complementary and contrasting colors, left and right directional orientations, and relative sizes and intricacies of the patterns and forms.

This “movement” produces the illusion of zooms, flickers, and slight “dances” of the relatively similar forms. That is, the fundamental cognitive patterning that we make of Persian Pickles as we watch it (“Persian rugs,” “Paisleys”) imbues to the film a visual continuity that makes it “move.” Mack is testing our capacity for perceiving animation within a vernacular form of abstraction, and the result is that we are able to see something akin to the “pure” motion that early modernist animators like Oskar Fischinger and Hans Richter were striving toward.

More than this, Mack understands that the material she has selected for Persian Pickles is hardly neutral. It is not just that it is more “of the world” than the abstract squares and triangles of Fischinger and Richter (and even some films by Breer). These patterns call to mind specific historical and cultural contexts: the Middle East, and Iran in particular, in the case of Persian rugs; and “the feminine” in the case of fashion and the decorative arts more broadly conceived. Mack is dipping into areas that have traditionally been kept off high modernism’s grand stage, since it was presumed that they were contaminated by ornament. If, as Viennese architect Adolf Loos asserted, “ornament is crime,” than Persian Pickles is a film that coaxes us to break the laws of pure perception in order to arrive at a new pattern language, one that we will take along with us like an afterimage.