Curtis Harrington is not a name that slips off the tongues of most cineastes, unless they are particularly versed in the American avant garde films of the fifties or the campy and colorful B movies of the sixties and seventies. And considering the names that pepper the pages of this little-known director’s recently published memoir Nice Guys Don’t Work In Hollywood—Roger Corman, Kenneth Anger, Stanley Kubrick, Jean Cocteau, James Whale, and Josef von Sternberg, to name just a few—it’s a wonder that his name isn’t affixed to more high profile projects than 1965’s Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet or the 1978 TV movie Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell.

Harrington ended up being an example of what is likely a typical tale in Hollywood: a director who gladly (and sometimes begrudgingly) took the work that was handed to him as he labored to get pet projects off the ground. His filmography looks like a scattershot run through everything from fractured art house shorts to campy horror to nighttime soap operas of the eighties. But if you start digging into the life of the late artist (he passed away in 2007), you’ll find a fairly incredible story built on a deep love of film, good fortune and a singular vision that shone through even his most commercial work.

“His aesthetic is so beautiful and thoughtful,” says Lisa Janssen, an archivist and film theorist who is working with Chicago-based imprint Drag City to bring the memoir and a DVD collection of Harrington’s early experimental works into the world. “Yet there’s a real camp element to it that’s so funny. He also retained this great sense of humor throughout his career. The combination of all of that is really beautiful.”

The same can be said of Nice Guys. The breezy tome plays to his expected audience, dropping as many famous names as he can squeeze in, while also taking readers through a quick and dirty history of his professional career and personal life. And it does what it should: inspire the reader to dig up as many of Harrington’s directorial efforts as possible.

As you would expect from the tenor of many of Harrington’s work, a lot of it is available for mass consumption: a DVD that pairs up two of his campier efforts, What’s The Matter With Helen? and Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (both starring Shelley Winters), and many other films streaming online including one of his most fully realized horror experiments, Ruby.

Another thread that runs through so many of these films is Harrington’s love of Hollywood’s Golden Age, which he tries to inject into even the most unusual projects.

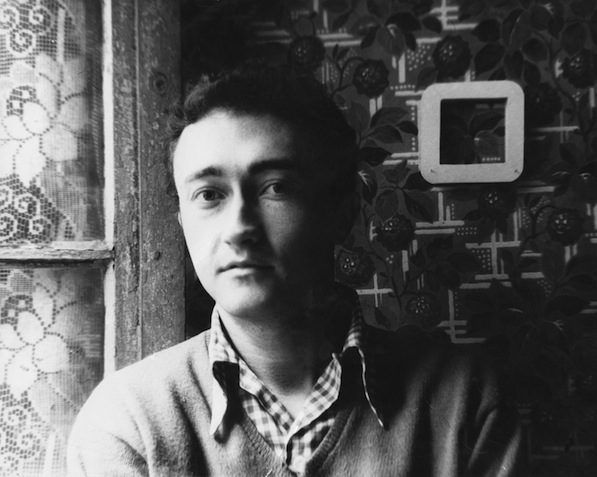

(Photographs courtesy the Curtis Harrington papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

He convinced Basil Rathbone to play the majordomo of a group of space explorers in Queen of Blood, while also going against producer Corman’s wishes to put former noir moll Florence Marly in the title role. He cast legendary British actor Ralph Richardson opposite Winters in Auntie Roo. And for a TV movie about a woman in control of a hive of killer bees, he gave the plum lead role to the great Gloria Swanson. “He talks a lot about how he really had a way with egotistical women actresses,” says Janssen. “Someone called him the next George Cukor because he was so good with those personalities.”

The title of his memoir should give you some indication of the struggles that Harrington dealt with throughout his career. He had a great aesthetic vision, which would be apparent to anyone who saw his striking early films, as well as his lyrical and beautiful first feature, Night Tide (based on a short story of Carrington’s, included as an appendix to the memoir). That certainly helped get him gigs in Hollywood, but his kindness was both his good fortune and his undoing in many ways.

He’s brutal about the shortcomings of certain films in Nice Guys, sharing the blame but also pointing out how key decisions made outside of his control kneecapped the production. And he laments that, in his later years, he was being seen primarily as a TV director.

“It was a huge heartbreak for him to end up there,” says Janssen. “What he finds is that you don’t just do one show and then go back to directing features. You’re marked for life. He just got stuck there.”

During that time, Harrington pleaded with movie executives to help him get films funded and produced. For the better part of thirty years, he tried to get an adaptation of Iris Murdoch’s book The Unicorn brought to the big screen. He also attempted to work on TV adaptations of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and a biopic about Swanson, as well as dozens of other big and small films.

Frustrated as he was, Harrington kept soldiering on, able to keep working thanks in no small part to his gregariousness with everyone he encountered along his life’s journey.

“I talked to so many people that knew him, getting blurbs for this book,” says Janssen. “Everyone said, ‘I’ll do anything for Curtis. I love Curtis, whatever I can do to help.’ He left behind a lot of goodwill.”

This article first appeared in Keyframe on June 13, 2013.