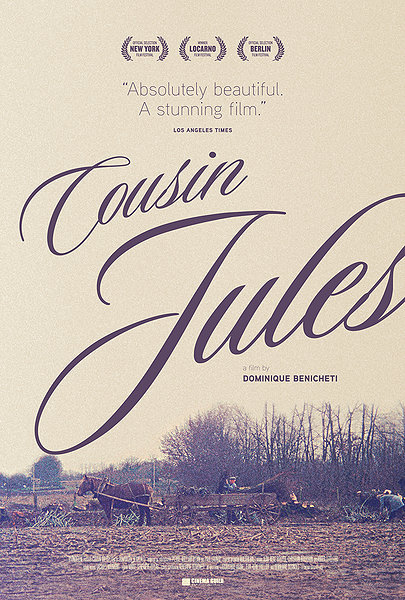

Some “lost classics” aren’t really lost, just misplaced for a while. Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1969 Army of Shadows may not have been released in the U.S. until 2006, but it was fleetingly available to American audiences before that in Melville retrospectives. French director Dominique Benicheti’s sole feature-length film, the 1973 documentary Cousin Jules, really is a lost treasure. Its two-week run at New York’s Film Forum marks its theatrical premiere anywhere in the world.

Ironically, Cousin Jules was a victim of its own technological innovation. Benicheti didn’t settle for the black-and-white 16mm of many documentaries of the sixties and early seventies. Instead he worked in color, CinemaScope and Dolby stereo. Most arthouses of the time weren’t equipped to show such a film, so it never found distribution in the U.S. or France (despite touring the festival circuit in 1973 and 1974 and winning a prize at Locarno.) Some of Benicheti’s subsequent shorts would experiment with 3D and 70mm.

Paradoxically, Cousin Jules is a technologically advanced portrait of people living in conditions that barely qualify as modern. It depicts the everyday lives of Benicheti’s cousins Jules and Felicie Guitteaux, an elderly couple living in the countryside near Burgundy. Jules works as a blacksmith, while Felicie tended to a garden. (armodexperiment.com) It’s never clear if the couple has running water, as Felicie has to draw water by a hand pump from a well for their morning coffee. Jules shaves with a straight razor. There’s no food market in the village where they live; instead, Jules buys bread and sugar from a man out of the back of a truck.

Benicheti’s images have a plainspoken beauty, but it’s hard to make a film that features no less than three scenes of vegetables being prepared for the table sound interesting. Yet Cousin Jules is quite fascinating and manages to make such chores more compelling to watch than they probably were for Jules and Felicie to perform.

The secret, which doesn’t come across in a ninety-second snippet, is an extraordinarily vivid stereo soundtrack. If Bresson and Tati introduced modernism to the French cinema’s soundscapes, Benicheti picked up the baton. While I trust that he didn’t add anything to the soundtrack, even the barest scenes are filled with audio, much of it contributing to a sense of lively offscreen space. The scenes of Jules at work are musique concrete symphonies, in which the sound of his shoes creaking on the floor competes with a crackling fire and tools clashing with metal. According to the closing credits, no less than three soundmen worked on the film.

Cousin Jules is much slicker than a seventies Frederick Wiseman film. However, Benicheti’s attitude towards his subjects owes something to the hands-off approach of cinéma vérité. He never interviews Jules or Felicie. Nor does he offer narration. His approach takes the screenwriter’s maxim “show, don’t tell” to the limit. The film was shot over the course of five years, between 1968 and 1973, but it looks seamless. Felicie died in 1971, but only in the closing credits do we learn of her passing. Jules doesn’t visibly age on-screen. Even the weather often looks much the same throughout the film. The farm’s colors are a wintry pastel.

Compared to other French films of the period, including documentaries, Cousin Jules seems like a whatsit. Filming began in April 1968, a month before the protests of May ’68, but they may as well have taken place on another continent. During the time Benicheti patiently worked on his film, Jean Rouch was busy filming in Africa. Chris Marker toiled away semi-anonymously as part of a collective making politically radical films. Marcel Ophüls assembled footage for his indictment of France’s behavior during World War II, The Sorrow and the Pity. Only Jean Eustache’s documentaries about rural life in France bear much resemblance to Cousin Jules, but they’re much rougher.

As for French narrative cinema landmarks of the period like Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating, Maurice Pialat’s We Won’t Grow Old Together and Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore, Benicheti’s film has nothing whatsoever in common with them. That’s part of what makes it so fascinating in 2013. It depicts a way of life that probably hadn’t varied in decades, but was likely to undergo some major changes thanks to the technology that Benicheti so enthusiastically embraced. The final scene, which shows Jules’ empty workshop, evokes Antonioni’s L’Eclisse in a far more modest manner. Without ever editorializing, Cousin Jules suggest that Jules may be the last of his kind.