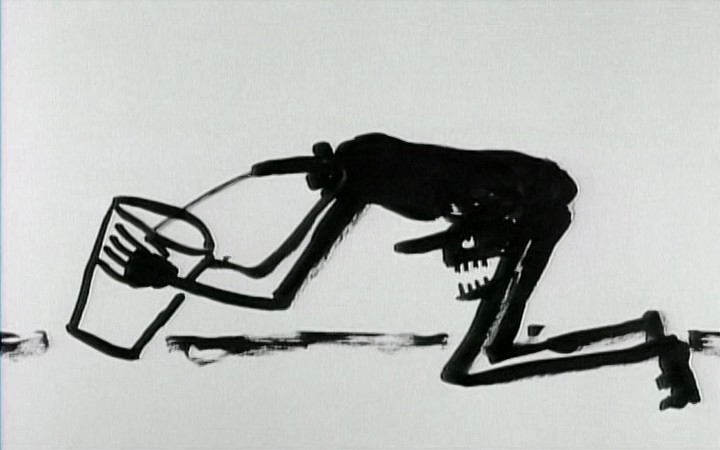

1. On the first day, there was a break in. The thief was unidentified but he left the renter bound and gagged at his piano. On the second day, the bruised renter wept. On the third, he considered escape, but obedience overwhelmed him. In a month he’d cry and shake like the newly incarcerated, and hit his face in frustration on the keys. Decades pass and spirits fly above him, taunting his muteness until he’s liberated from this mortal coil and ascends with his piano. Preening over crowns, God finds his playing super annoying. As angels dance, this Heavenly Father squelches the enduring spirit of man because it’s a freaking nuisance. Thou Shalt Not Adore False Gods, indeed.

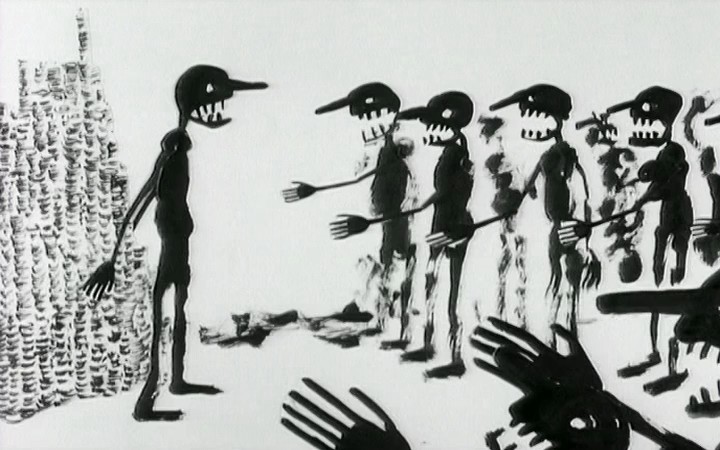

Phil Mulloy’s animated Ten Commandments critique the titular holy rules at the same time that they find humor in their existence; unlike Dante’s, this comedy is bitter and bleak; like kidney pies to Dante’s chicken piccata.

If you’re in my generation you might remember a bizarre little cartoon short that played on early MTV. Two pointy, stick-like boxers stop their fighting in the ring and, to demonstrate peace to the ferocious masses, hug for all to see. The crowd, having none of it, screams for blood and delivers unto the boxers the violence they nobly backed away from, now with vengeance. That short was just long enough to shock us, disgust us and produce an uncomfortable, if knowing, laugh—and then Tabitha Soren would come on and said another something newsy. We should name the phenomenon “mulloy.”

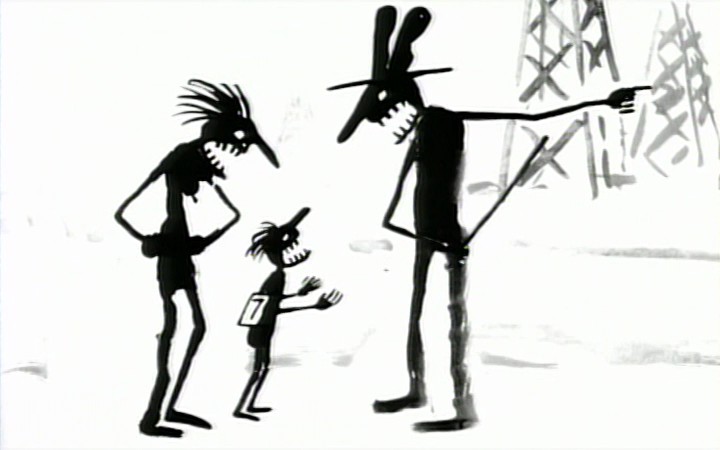

2. Whatever the point is, we just better not mess up. Zeke, the unfortunate churchgoer who yawns during services in Thou Shalt Not Commit Blasphemy is punished for his insulting oxygen depravation with a front row seat to the alien apocalypse. It’s in the smaller, less mysterious commandments that absurdity and hypocrisy seem most evident. God isn’t even turning his head to notice the commandments broken in films Two and Three. Maybe God would get involved if he found the crimes more entertaining but this God is no guardian of justice.

It’s possible also that Zeke’s crime (yawning) and punishment (torture by aliens from planet Zog) aren’t related under the higher power of the Lord; and us viewers are just stupidly assigning causality because that’s how movie logic works. Who says the yawn started the extraterrestrial inquisition? God didn’t. Plus, Zeke might be a loon; these demonic mini-aliens are awfully close to him (inside him?). Maybe these commandments prove religion, like most manmade inventions, are full of fussy pitfalls.

3. Remember to Keep Holy the Sabbath Day brings us new zogs. These have penis heads and faces in their laps. In comparison to the Zogs of Commandment Two who are short and fiery, these guys are layabouts. They plot for world domination but mostly just drink, so when Zeke stops their drunken machinations by reminding them it’s Sunday they make way to their penis-headed savior statute to pray—during which, I presume, some audiences of the Commandment animations might be deeply offended and zogs might yawn.

The emphasis on the aliens is a masterful and bothersome ploy. It strips the religion from the commandment and shines a brighter light on the absurdity of extra-human punishment. Don’t get me wrong, karma is just as touchy to represent (it almost always looks specious), but this series is too literal and impatient for “what comes around goes around” philosophizing. Mulloy grapples for answers, or at least finds truth in the humor: rules describe crimes and imply punishments and in literalizing the pattern a system reveals itself. This is worship, in its way, and I hear you can’t worship wrong.

4. In ten commandments we have eight statements on what not to do, and only two that say what to do. Honour Thy Father and Thy Mother is likely the most poetic and sensitive of the bunch.

A young boy is forced to run in the county races and when he loses, after much cajoling and minor abuse on part of his parents, he honors their parental violence with some of his own. If they survived they’d be proud—then again, pride was a pretty foreign emotion to them before the screaming started so maybe not. It’s a rough world.

5. When a suffering farmer loses his wife, three kids and dog (accidents all), he kills himself in heartbreak and the creator is not sympathetic. Thou Shalt Not Kill points out the cruelty inherent in reading suicide as murder, a perspective practiced in both religion and laws, emphasizing the idea these rules are guides for what to punish, instead of guides for better living. Poor, poor Farmer Josh. Even his dog died…which, in retrospect, was kind of adorable. While there’s little joy in this world, it does sometimes feature bodies anyone might cherish.

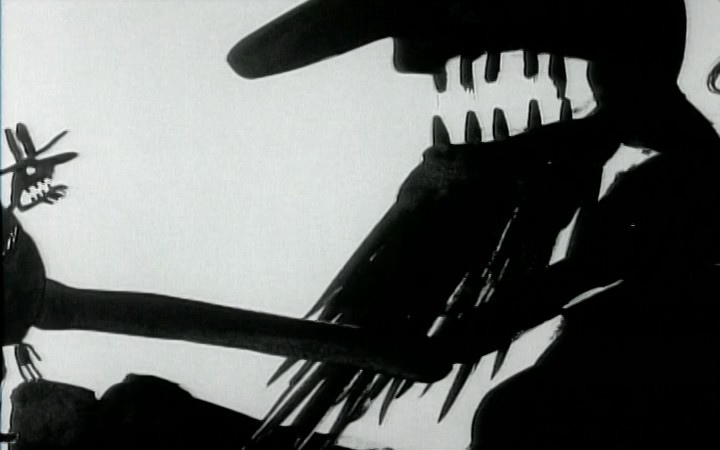

Mulloy doesn’t question the existence of a creator, though he does allow the influence of aliens and economics to suggest our concepts of “higher powers” might lead to confusion. For these semi-literal depictions of the ten rules of Christian life, God is just a grotesque avatar five times the size of his worshippers. He may or may not have handed down these rules (likelier not) but Mulloy’s mocking Lord is still biblical in the old sense. He smites those who bother him and is immune to suffering. Unlike other visions of the Holy Father, this inky, splotchy monster knows more than everyone and is in no warm mood to share. I think this proves Mulloy is so British it could kill him (if his god doesn’t get to him first).

6. Murder, idolatry and disrespects aside, you knew the saucier commandments had the potential to be the snarkiest but instead they’re the most tragic. Somehow, locating blasphemy so close to screwing makes it all the more arbitrary a cause for punishment. More than any other Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery asks for a relative solution.

A male and a female astronaut are shanghaied in space when international capitalism crumbles and as they misremember their miserable marriages as honorable ones, they vowed not to find comfort in each other’s arms. Horribly lonely, their guilt turns to madness. The only happiness to be found is among the flies that eat them and screw freely without commandments of their own. The heathens. See what befalls people who dream of flight?

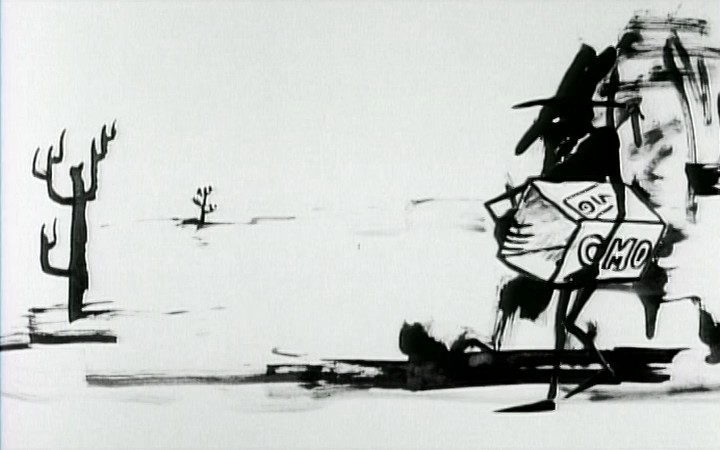

7. Only the homeless are holy in Joestown, where Cisco employs everyone until the higher ups kill themselves and the company collapses. In secret, their employees pilfer their supplies, but not our protagonist, who “is a good man. A God-fearing man,” and who adheres to the rule Thou Shalt Not Steal.

Mulloy sees him equivalent to a passive man, because when he’s evicted and left to live in a box by the road, he lodges no complaint either to his society or his creator. His silence is more proof he’s good, God-fearing and submissive.

8. Based on the commandment most frequently misread as “thou shalt not lie,” number eight is perhaps Mulloy’s most trenchant episode. Thou Shalt Not Bear False Witness is about the battle inside the hearts of a middle-aged husband and wife, happier to sleep than share their desires with each other. The most provocative image is that of a fire; fire is a regular fixture in these commandments as a catchall for destruction, but this fire burns within. Doors close over the flames, both to contain and hide them, and that image of closing doors evokes the central anxiety of these shorts.

It’s not just the commandments are artifacts misread by millions and preached to encourage obedience, it’s that people internalize that preaching and ignore whatever burns within. It’s sadder than unmoored astronauts or suicidal farmers; it’s active suffering, self-inflicted as we declare ourselves the masters of our own emotions. It’s also the most incisive paradox of the lot because if these rules exist to lead us into harmonious living with God, if they help us become examples (or in the case of this short “The Holiest People In Joestown”), we succeed with them at our own behest. The pops of color add no grey to the black and white imagery. Like the pianist renter in Thou Shalt Not Adore False Gods, the constraints are cutting until we resign to them and we resign with a whimper.

9. What’s great about pettiness is it’s funny, which is how we begin with Cisco, who, you might recall, picked up his business in Joestown and now moved to a town full of “mestizo scum” where he built a rudimentary electrical system (used to torture people) and since the world loves torture he’s made millions manufacturing. Yet, Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbour’s Goods, and the scum who covets his goods launch an insurrection that God and the local law (purchased at wholesale) suppress, sending them to the relatively luxurious clutches of Hell.

Never before did the rules of genre seem to bear on the subject so mightily—well maybe it mattered as much when we cried for the astronauts—but our feeling for Cisco’s villainy equate to a desire for justice and isn’t that the root of law? The commandments, however, aren’t precisely law, they stand in for it, inform it, resemble it, but laws require enforcement and nothing says anarchy like people getting away with murder, theft and random acts of capitalism.

10. As the commandment suggests, Thou Shalt Not Covet Thy Neighbour’s Wife has the most moving parts. First Buck loves his neighbor and follows her out when she takes her beloved dog on “walksies.” If he could only trade roles with the dog…so he makes it happen and in the process accidentally kills the prime minister, beginning a nationwide manhunt he’s temporarily immune from because he’s dressed as a dog. But Buck is a pathetic excuse for a dog and his lover takes to beating him; meanwhile the dog is getting along splendidly with Buck’s wife. If backward, this is the single commandment film in which justice is done, and yes, the justice is accidentally accurate.

Mulloy is one of those rare shorts animators whose built a name on his characters. These grotesque little avatars toil and aspire, like all movie creatures, to bring hope to the world, and because we’ve all seen movies and know that those who work will win and those who yearn will be rewarded—we expect good to come their way. All while their creator, Mulloy, titters at their yearning.