A conventional way of looking at art is that a good picture is one that looks real and that a bad picture looks crude and unreal. The 2007 documentary My Kid Could Paint That rests on the idea that abstract art is something of a hoax, debating whether the highly prized (and priced) abstract works of a girl have real artistic merit, or whether the girl still needs to learn to color inside the lines.

However, within the world of cel/hand-drawn animation, fine draftsmanship and free-form renderings have coexisted for decades. Despite his fanciful subject matter, early animator Winsor McCay’s elegant style set a standard for representational drawing that eventually found favor in Disney feature films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Just as surely as there were animators anxious to conform to the Disney style, there were others who felt straitjacketed by in. Several Disney animators, propelled by an animators’ strike in 1941, formed what became United Productions of America (UPA), deriving their inspiration from abstract expressionist artists like Pablo Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky. One former UPA artist, Chuck Jones, eventually won an Academy Award for his 1965 animated short The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics, a largely abstract film in which all of the characters are geometric forms.

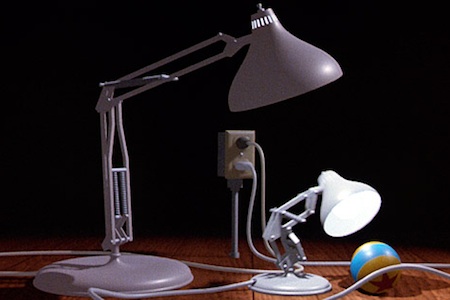

In 1986, a new kind of dot and line entered the animation field—more precisely, a “0” and “1.” Upstart animation director John Lasseter, working at Pixar Animation Studios, premiered the first 100-percent computer-generated (CG) cartoon, Luxo Jr. The film’s hopping desk lamp not only became a symbol for Pixar, but cast the light of invention over the moribund animation industry in the United States. The first 100 percent CG animated feature, Toy Story, premiered in 1995. Disney purchased Pixar in 2006, and in 2012, the top seven highest-grossing animated films were all 100-percent CG. Only one hand-drawn film, The Secret World of Arriety, cracked the top ten (in the number eight spot), and it came from Japan, where traditional animation is still a living art. Two stop-motion animated films, The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists! in an Adventure with Scientists! and Paranorman, came in at ninth and tenth place, and it could be argued that the smooth lines of both of these films mimic the look of CG animation.

Given Disney’s long history of preferring representational art, its embrace of CG animation was a given. Other Hollywood studios also have embraced CG animation as more efficient, and the heavy promotional arms of all the major studios should ensure that public tastes will be shaped by the proliferation of regularly shaped geometric forms.

Perfectly formed spheres and utterly straight lines—even flowing strands of hair as can be found in such films as Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001) and Brave (2012) have perfect curves—create a kind of sterile hyperrealism within the most imaginative story and have a tendency to dull the visual palette. Constantly viewing images made of perfect lines perfectly filled with color, even nature-defying color, creates a generic conformity that undermines the individual visions that can be found in pre-computer animation.

Let’s go back to The Dot and the Line. It doesn’t skimp on geometry, and seems to promote the mechanics of shape-shifting, now so inherent in CG animation, in providing the kind of variety missing from our work-a-day lives. To take such a lesson from the film, however, would be to overlook the real point: the urging toward creativity. A simple line can become so many dazzling things with a little practice, showing the tangible rewards of literally thinking outside the box in a film created using traditional cel technique. The hand-created variations in the straightness of the line and the jazzy unkemptness of his rival, the squiggle, give these abstract forms character that a 100-percent CG film can approximate, but never equal.

The question audiences have to ask is what do we want from animated films? Do we just want eye candy, intense colors and perfectly formed clown fish and toucans that show the human power to recreate nature to the smallest detail? Photographers can capture reality easily enough, but often choose to create blurred, superimposed, or textured images that can disturb, enlighten, and inspire viewers with an original point of view. Some animators, such as Nina Paley with her inventive feature Sita Sings the Blues (2008), apply mixed media to their CG work. Paley, for example, includes scanned cut-outs of Indian gods as well as hand-drawn frames to put the stamp of her personality on a work that can awaken viewers to their own expression and enjoyment.

Mainstream animation, now almost exclusively employed to make films for children, is offering a vision of the world today that promotes coloring inside the lines. I personally don’t think that’s a good thing. How about you?

Marilyn Ferdinand is a freelance writer and regular contributor to Keyframe. She is the founder and coproprietor of the film criticism blog Ferdy on Films (www.ferdyonfilms.com), as well as the For the Love of Film: The Film Preservation Blogathon.