Editor’s note: This is the final in a series of twenty-four articles on the films of Werner Herzog. For a complete list of pieces, see “Werner Herzog, Collected,” here on Keyframe.

In the great tradition of tormented artist iconoclasts, Werner Herzog has never reconciled his obvious affection for quixotic rebels with what their quests often represent: the imposition of the might of the few upon the weaker masses. Herzog’s aware of this irony, and his refusal to smooth over the fascist implications of his grandest dreamers’ dreams is one of the wellsprings of his art’s complexity and of its principle. The filmmaker’s only pivotally fallen from this tonal tight-rope once, and the result was Fitzcarraldo, one of his most beloved movies.

In that film, a misfit played by Klaus Kinski, who’s largely living from a kindness of others that affords him his ability to cultivate his bohemian obsessions, risks an untold amount of tribesman lives so as to access a remote jungle forest of rubber trees, which will net money that can initiate the building of an opera house in Peru. It’s a ludicrous aim, and Herzog knows it. But the filmmaker doesn’t inform this story with the ripe, primordial imagery that often reliably invigorates his work; instead, he flattens the images out, probably to achieve a parody effect that never comes into focus. What remains is sentimentality with a weirdly unpleasant aftertaste. The film doesn’t allow you to enjoy the hero’s quest (the most famous sequence, in which a steamboat is dragged up a mountain, is better read about than watched), but it doesn’t have any satirical energy either. The ironic ending, which is rendered un-ironic with sweeping camera gestures that would be romantic in a clearer context, comes as a confusing sop. After two and a half hours invested in something grandly negligible— which wasn’t that enveloping to begin with—the audience is left with only the negligible.

Cobra Verde now plays, retrospectively, as an inadvertent correction of Fitzcarraldo. It’s one of Herzog’s bleakest and most disturbing films, and the director seems emboldened by the alienating challenge of the material. This is a film in which the dreamer is understood—in the spirit of the great Aguirre, the Wrath of God—to be a vitally complete bastard. Francisco Manoel da Silva (Kinski) doesn’t have any ideals that allow for transcendent platitudes that can paper over the human and ecological cost of said ideals. Lope de Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo pursued boy’s definitions of glory and power; they’re tyrants, but they had just enough naiveté to allow for a perversely fatalistic sort of adventure-film wish-fulfillment. Da Silva doesn’t. A 19th-century Brazilian rancher turned miner-turned-outlaw, the man’s an aggressively debased embodiment of survival as its own reward. Chillingly, Herzog and Kinski display that da Silva isn’t a bastard because he’s in dire straits, but a bastard with a constitution that requires him to be forever in dire straits (this is his closest approximation of possessing a “dream”). Masochism appears to be eating him alive, and he’s more than willing to spread the wealth.

This understanding empowers Herzog to fashion the most unsettling images and sequences of his career. Da Silva, soon known as the dastardly Cobra Verde, eventually gets himself in with a wealthy sugar baron named Don Octávio Coutinho (José Lewgoy), who doesn’t initially know of the former’s fame. Coutinho proceeds to lecture da Silva about the ease of maintaining the servitude of the plantation’s black workers, outlining, with amusing bluntness, the trickiness of providing Britain with most of their sugar despite their banishment of slavery. It’s a great debauched moment—an offhand deflation of real-life hypocrisy—and Herzog has the daring to allow you to enjoy it. You’re responding to the outward force of Coutinho’s personality, disgusting though it may be, and to da Silva’s bored revulsion, which isn’t couched in any kind of humanist outrage, but in an impatience to get to the good stuff. Da Silva, strikingly, doesn’t even have the boastfulness of many doomed crusaders in the key of Kipling and Conrad: He just wants to sate himself on spoils.

Said spoils are vividly illustrated by a passing but important moment that immediately follows the tour of Coutinho’s plantation. Coutinho flouts the many children he’s sired with the slaves (he’s celebrating his aging virility as well as the dilution and potential annihilation of a race), and a gorgeous black woman approaches him on a balcony of his huge mansion, leading to their exit to a nearby bedroom. That’s about as much as you see, but it’s a powerfully sexual moment that haunts the rest of the film. It’s disturbing because Herzog’s willing to allow it to be conventionally erotic, particularly in terms of the woman’s “come hither” gait. Herzog doesn’t reduce this exchange to being just about Coutinho’s moral rot; you feel the primal, physical allure and pull of power and its attending rewards.

Cobra Verde allows you to see da Silva as both an oppressor and a member of the oppressed, as he sort of embodies an idea (very resonant in American culture; especially of traditional American gangster film mythos) of the villain who commits great evil to avenge classist exclusions, though Herzog and Kinski exhilaratingly chafe at rationalization. Da Silva might want what Coutinho has: masculine self-actualization, which he samples through his dalliances with the plantation owner’s daughters. Or he just might be passingly horny. Either way, as a punishment da Silva is sent to West Africa on a mission that’s intended to kill him, though his zeal perseveres: his detachment from conventional inspiration is his power. He establishes a slave trade with the inhabitants of Dahomey against the odds, until laws arbitrarily destroy slavery and render the great white warrior obsolete.

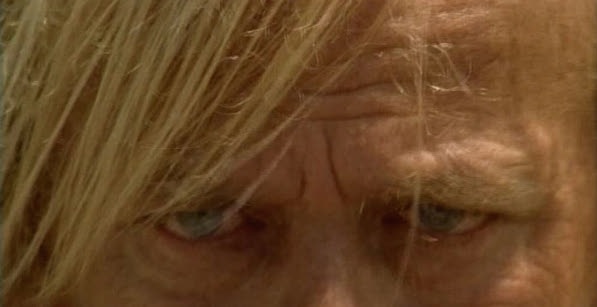

Herzog’s cavalier indifference to plot coherence serves Cobra Verde, informing it with a caged, irrational dream-like force. This film is disjointed and episodic (the first act, a misleading Jodorowsky-tinged western, imparts little in the way of conventional exposition, though it establishes the rules of the film’s defiantly subjective game), and, for that, a feeling of deep futility characterizes da Silva’s actions that’s reinforced by the African political infighting that will initially benefit him. We’re given little context of the process of da Silva’s exploits, or of the retribution they incur, because the director appears to deem such specifics to be beside the point. We’re privy to the exertion of will, primarily da Silva’s and the African kings’, which is represented by bold compositions that emphasize royal processions or show us the slaves as they’re being rounded up in images that are suggestive, in their mixture of mathematical precision with rapt anger, of a collaboration between Busby Berkeley and Goya that’s set in the ninth circle of hell. (The slave lines are just another procession.) Alternated with these passages are electric shots of desert landscapes that are punctuated by close-ups of Kinski’s fleshy-yet-angular face. Herzog achieves a double-point-of-view similar to Martin Scorsese’s perspective in The Wolf of Wall Street: he conveys the damage a madman has wrought via his own distorted vision of himself as a god, and establishes the temptations of that vision: the charge of domination, which drives the various power-mad figures to take turns killing and overthrowing one another in an incendiary cycle of cruelty and pointlessness. This film has an emotional intensity that’s informed by parody of pride as spiritual corruptor.

Kinski intensifies these contradictions, mysteries, and intangibilities. In Fitzcarraldo, the actor often seemed disengaged from his surroundings, while in Cobra Verde he commandingly plays disengagement. Kinski doesn’t ultimately provide us the comfort of contemplating da Silva as an avenging oppressed figure intent on proving that he can be a big consumptive cheese like Coutinho. Da Silva’s an animal figure, which isn’t surprising coming from Kinski, but he’s an animal who doesn’t seem to want anything; potential early explanations of his actions go up in a psychologically evasive puff of smoke. He just does, and his damnation at the end doesn’t even seem to matter to him anymore than it does to anyone else. This distance weirdly draws us closer to da Silva: his one admirable quality is that he seems to know how internally puny he is, and we sense his understanding of that quality in how little he attempts to atone for himself or to enjoy the temporary fruits of his carnage. Da Silva’s force is just there, demanding expression, and Herzog and Kinski are in irresolvable awe of its operatically amoral purity.