While one of the most talked-about films of the year, Gravity, is set in outer space, the majority of films—in accordance with the origins of cinema—are about cities. The best ones take the urban environment as an element that fortifies dreams and nightmares, a machine that, like cinema, generates emotions. Many of which are conflicting in the past two years, as films endorse, reject or complement the image of city in other films. Woody Allen’s shallow, touristic view of Rome in To Rome with Love is nullified by Sacro GRA’s dark humor and its almost anti-Roman narrative. The hysterical, prison-like image of Tehran in Argo (with mosques in the Turkish style, which is like making a film in San Francisco but showing the Brooklyn Bridge instead) is challenged by the lively, crowded, class-divided Tehran of Parviz. Even the sci-fi Tehran of Taboor, which is devoid of human presence, has more to do with the reality of Tehran than the multi-million dollar film.

The deteriorating city is the backdrop of some other films in recent memory, like the Detroit of Searching for Sugar Man and the decling city Only the Lovers Left Alive’s characters leave for the ancient city of Tangiers. The search itself for the city was a key theme in the films of the year, where, for instance, in The Last Time I Saw Macao, João Pedro Rodrigues and JoãoRui Guerra da Mata look for the lost Macao of Jane Russell and Robert Mitchum and its Portuguese colonial legacy only to find the eroticism of neon lights and the boredom of cheap hotel rooms.

Finally, the city can be the scene of a bidding farewell to life, as in Raúl Ruiz’s swan song, Night Across the Street, in which the filmmaker returns to sunny Santiago to write his cinematic will in the city’s empty alleys.

The ten following films represent my favorite cinematic cities of 2013.

10. Cairo : Rags & Tatters

Deconstructing the myth of Tahrir Square via the war-stricken, chaotic Cairo in the days of the coup or second revolution in which Mohammed Morsi saw his downfall. It is narrated from the point of view of a fugitive, which makes the whole ensemble look like an Odd Man Out shot by a mobile camera. The film’s images, charged with a sense of urgency, are reminiscing of those militant self-distributed YouTube videos which go online shortly after an incident in the middle of the revolution.

9. New York: Inside Llewyn Davis

The freezing New York of the Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, though an unkind place for any wanderer, never loses its charm on celluloid.

8. Tehran: Seconds of Lead

Tehran is depicted as a two-faced city, in which one face is a merciless metropolis, and the other is a city of motion and creation. This 2012 Tehrani film by Seyed Reza Razavi, recommended by Chris Fujiwara, tells almost the same story as The Act of Killing (summoning the traumatic past—here the massacre of revolutionaries in Jaleh Square by the Shah’s soldiers—a recounting far shrewder than The Act.)

Made with Claude Lanzmann’s persistence and Marcel Ophuls’ uncanny humor, Seconds follows the story of a woman who, against all odds (including downtown Tehran’s impossible traffic jam), tries to convince a cinema projectionist, who had witnessed the massacre, to talk on camera. But after a while the history becomes sidelined by the story of the cinephile projectionist and Seconds turns into a celebration of love for cinema.

7. Berlin; Oh Boy

There have been cinematic cities built more on the image of that city in cinema than the actual place. Mosaic films that are composed of a hundred of pieces from film history can ultimately create the identity of the celluloid city. If Frances Ha’s New York was filtered through French cinema and Francois Truffaut’s graceful city pieces, Jan Ole Gerster’s black-and-white Berlin was an updated Berlin of Menschen am Sonntag and German “Street Film” of the twenties.

6. Tirana: Here Be Dragons

The title of Mark Cousins’ diary of a trip to the capital city of the least-known European country, Albania, derives from a Latin phrase which used to be written on maps, marking the dangerous or unexplored territories. Cousins sets out to discover a country whose borders Werner Herzog had once marched around, after being forbidden entry. In the process, the filmmaker/voyager creates an important and enlightening document about Albanian culture, people and cinema.

5. Berkeley: At Berkeley

Although the camera hardly leaves the university campus or ventures into the city itself, Wiseman approaches his object like an urban documentary in which everyone from the mayor to the road sweeper are parts of a precise mechanism. Wiseman’s film is like an urban symphony without music that is instead harmonized by the sheer energy of collective life and the struggle to keep it intact.

4. Nablus: Omar

A two thousand-year-old city with winding streets, bullet hole-covered walls, and tangled houses hosts a Pepe lo Moko-esque tale of love and betrayal by Hany Abu-Assad. Here, the representation of the Palestinian’s city is inspired by American cinema and, as in Scarface, billboards promising a better life are winking in the background. However, Abu-Assad’s art lies in splendidly tying the generic homage to the Palestinian dream.

3. Terezín/Theresienstadt: Last of the Unjust

One of the most brutal cinematic cities in the history of the medium is the Warsaw ghetto in Shoah, a city we never see but fully “hear” and imagine in descriptions given by two or three of the survivors. Last of the Unjust is another example of such a city, where unlike “normal” cities whose function is facilitating life, the business of death and destruction rules. For Lanzmann, oral history more than any other means can reflect the memories of the twentieth century Europe’s nightmare cities.

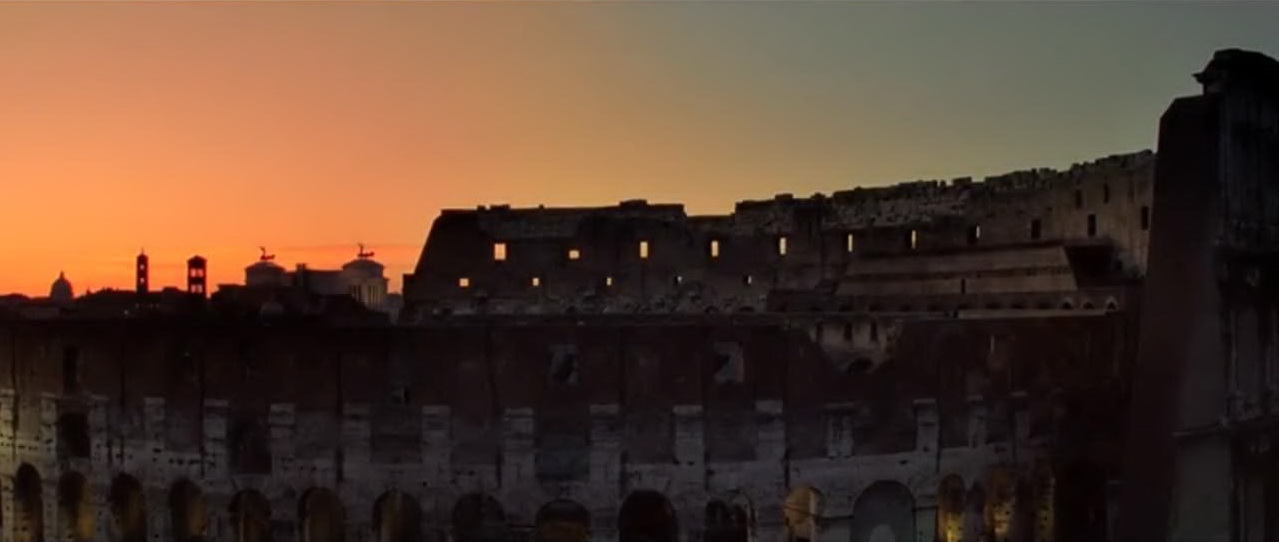

1 and 2. Roma: Sacro GRA+ La grande bellezza

Two Roman films that complement each other: in Sorrentino’s masterpiece Rome is the city of piazzas, huge marble sculptures and the blabbering idle intellectuals whose 24-hour party life hardly bears any relation to the ancient grandeur of the city. (If Romans used to party as much as the characters in this film do, no “beauty” was ever created in Rome). Rosi’s Rome, like Lanzmann’s “concentration towns” is never shown, mostly because the film stays on the fringe of the city and wanders around it on the ring-road highway where the strangest collection of people live. It feels as if people of the GRA highway (whose traffic jams are as exhausting as the parties in La grande bellezza) are doomed to ride on it forever, without being granted the permission to enter the city.People in both films are grotesque players who are performing a Luigi Pirandello play on a huge stage called Rome, day in, day out.

For the complete list of year-end lists on Keyframe, go to The Year in Film: 2013.

For the complete index of the films on these lists, go to 2013 Year in Review: Indexed.