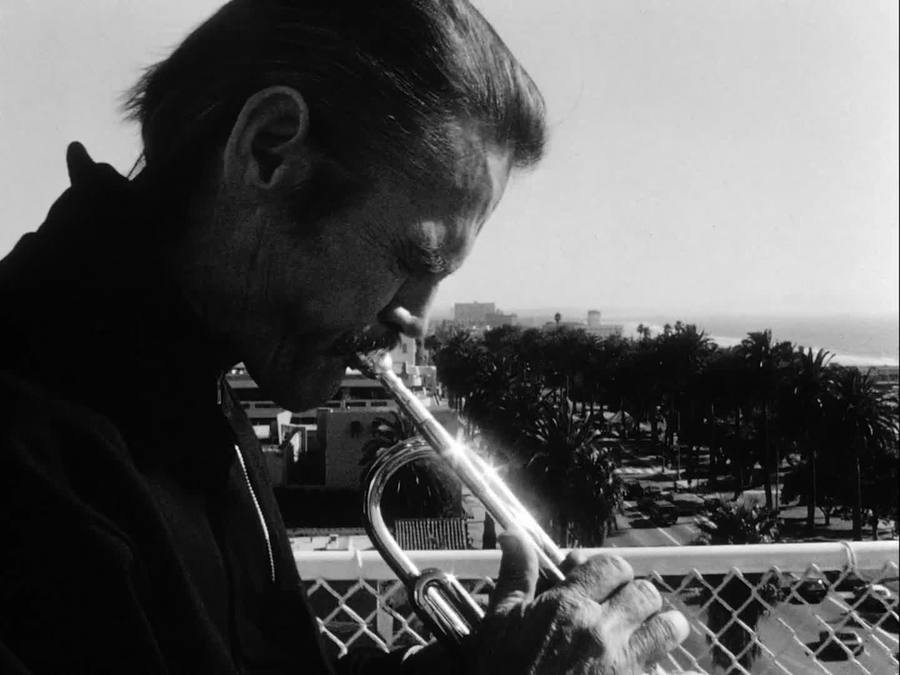

1987, Santa Monica. Chet Baker is weathered and worn. Filmed in black and white in the back of a convertible at night, framed by a pair of lovely young models, with street lights and headlights catching his features in a slash or a flash, his once smooth cheeks are leathery with age beyond his years and his face is sinking in to his skull as if his youth was eaten away from within.

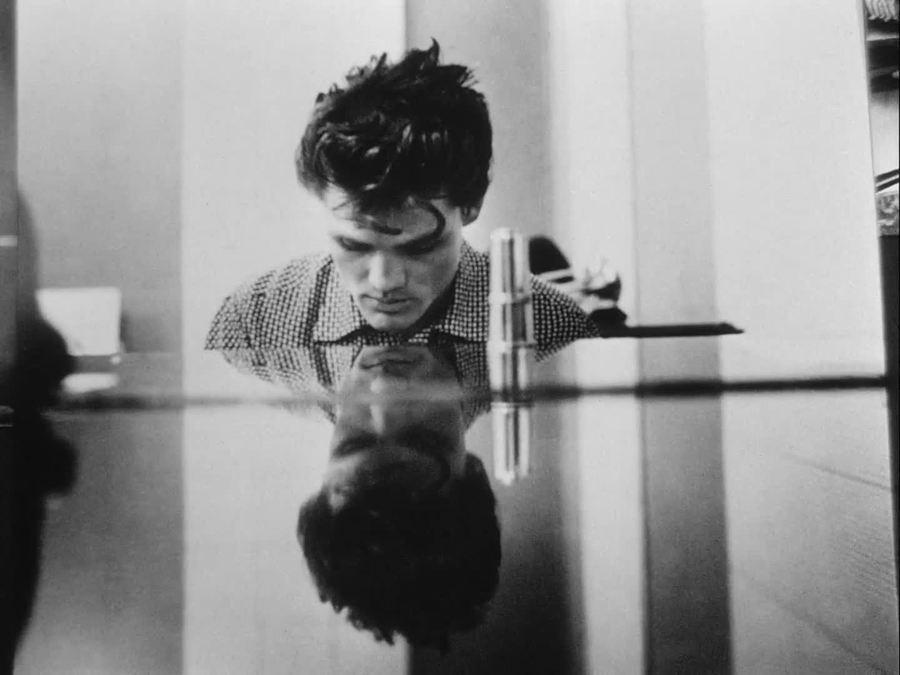

1953, Los Angeles. The contact sheets of William Claxton’s photos from a recording session picks Chet Baker out of the ensemble. Holding his trumpet with an easy nonchalance, hanging with a laid-back presence of knowing he belongs, with eyes as soulful as James Dean and hair like Elvis Presley and cheekbones that look carved by Michelangelo, Baker is the young Adonis of cool jazz.

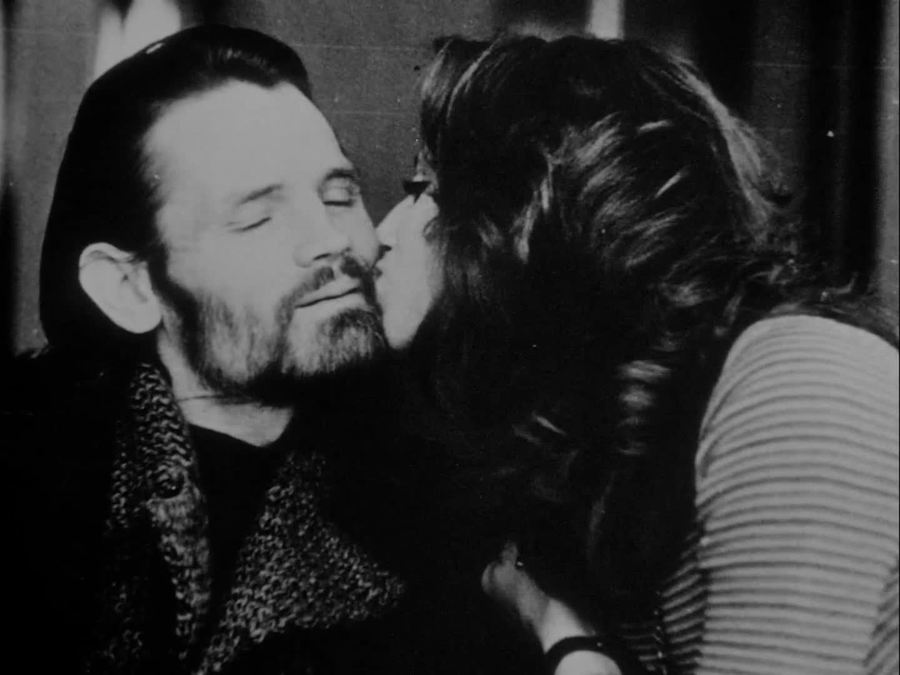

“He was bad, he was trouble and he was beautiful,” remarks a former lover, one of many tossed overboard to the choppy waters of his life. In the lens of Bruce Weber’s documentary, however, he’s still beautiful, a survivor wearing the scars of a turbulent life to a fashion shoot, the stark black and white picking out every scuff and wrinkle like it was earned. What we first see as a “seamy looking drugstore cowboy-cum-derelict,” in the words of Village Voice film critic J. Hoberman, takes on a ravaged grace through the course of Let’s Get Lost. In part that’s due to the hushed spell of his singing voice on ballads from the American songbook but mostly it’s because of Weber’s gaze.

A photographer turned filmmaker, Bruce Weber loves faces: smooth and rough, gentle and haggard, young and old. Baker is all of these and Weber trains his camera on Baker to get an intimacy with his subject, or at least the appearance of intimacy. Baker is utterly at ease in front of the camera, as if he’s spent his life playing to it, and he seems open and authentic as he talks about his past. The high-contrast cinematography gives that rough road of a face a kind of majesty and Weber is as entranced by it as he is with the talent behind it. Music came easy to Baker, we’re told, and his singing is apparently a lucky afterthought. Like his looks, he seems to have taken his talent, and the adoration that came with it, for granted. Maybe that’s why he became so cavalier with his loves and his life, though Weber would never suggest so. He’s not interested in a psychological profile. He’s fascinated by the figure, the image, the cool jazz matinee idol who seemed to embody the ideal of the young artist as rebel. Even the most sordid revelations of his life—and there are many in this portrait—and the toll of decades of drug addiction fail to dim the charisma of the fifty-seven-year-old jazzman. At least when he’s singing or playing.

Let’s Get Lost soars on these contradictions, the angelic voice of a one-time gorgeous rebel with a trumpet coming from a man who sells out friendship for his next fix, the romantic spell cast by his still youthful singing tone (his age and wear are betrayed by the slurs of his delivery and a slightly smoky edge) and effortless trumpet lines from a man who has spent his life disappointing wives and lovers and children. It’s not a matter of foregrounding the contrasts as finding them part and parcel of the package and still getting seduced by the voice, the horn, the image. Especially the image. Almost any frame of the film could be an album cover.

The documentary is named after a song that Baker sang on his second vocal album but it also captures the way he lived his life, ducking responsibility, diving into drugs for three decades as a junkie, all but abandoning his wives and children for the itinerate life playing music and getting high. Another ex-girlfriend describes how Baker was a reflexive con man, playing upon the sympathies of friends who knew better when he was short of cash for his next fix. There’s a chagrined affection along with the bitterness of the remembrance, as if the spell of Baker’s enchantment hasn’t completely dissipated even after all these years. Are those tales exaggerated? Weber lets Baker answer the question by recounting (with some pride) how he conned his company psychiatrist to get out of the army and telling the story of how he lost his teeth after being assaulted in 1968. Baker’s version of events isn’t exactly heroic but he does paint himself a kind of hapless victim. Others aren’t so sure of his innocence in it all.

Let’s Get Lost is neither hagiography nor hatchet job, and it never pretends to be fair and balanced. You’ll get some facts and a lot of stories that you can’t necessarily take on complete faith, but Weber isn’t concerned with learning Baker’s musical inspirations or improvisational approach and doesn’t worry about meeting the familiar biographical expectations. He’s simply fascinated with Baker and even more so with the image that he embodies and perpetuates with his mythmaking remembrances, turning self-absorption and reckless living into a portrait of a rebellious life in the company of jazz greats and adoring fans. Weber is not one to pass judgment (though he’s happy to let others share theirs) even when he reports the rather sorry death of Baker at age fifty-eight, not long after he conducted his last interview for the film. He’s still taken with that image, the face and talent that charmed and seduced friends and lovers and fans for decades. Even after death, he still casts a spell.