A centennial is such an arbitrary celebration. Yes, 2014 marks one hundred years since the beginning of Charlie Chaplin‘s film career, and the creation of his iconic “Little Tramp” character. But what do we know about Chaplin and his films that we didn’t fifty years ago, when he published his autobiography, or twenty-five years ago, when we celebrated the centennial of his birth?

For one, we can see better how deep Chaplin’s influence into cinema goes. As the first star and director to attain international celebrity status, we can find his mark almost everywhere, but he’s been a particular inspiration to great filmmakers such as Ernst Lubitsch, Walt Disney, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Renoir, Chuck Jones, Jacques Tati, Federico Fellini, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen and Abbas Kiarostami. He continues to be felt in the motion pictures of the twenty-first century. What is the most talked-about scene in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, in which Leonardo DiCaprio and Jonah Hill turn a misjudged quaalude adventure into an appalling, hilarious pratfall ballet, but just the most recent example of a tradition of slapstick inebriates tracing its cinema lineage to early Chaplin drunks of Mabel’s Strange Predicament, His Favorite Pastime and The Rounders? And though Sacha Baron Cohen may have built a career out of letting a constructed character loose in the real world with cameras there to capture the not-quite-documentary, not-quite-narrative results, it’s nothing that Chaplin hadn’t tried in early 1914 with the the first public unleashing of The Tramp in Kid Auto Races at Venice.

There’s probably been no better time to explore Chaplin’s life and films. Since the publication of My Autobiography in 1964, there have been dozens of published Chaplin biographies including essential ones from David Robinson, who is as careful to chronicle what he doesn’t definitively know about the star’s life as what he does, and from Jeffrey Vance, who updates the scholarship record and compliments it with an astonishing array of photographs. There have been tremendous efforts to restore nearly all of his films and make them available to modern audiences. The Chaplin Keystone Project teamed three major European archives and their global contacts in an effort to scour the Earth for the best-possible copies of the films made during his first year in movies; the results can be seen on DVDs released by Flicker Alley, and streaming here.

A centennial is also an excuse for a communal gathering, and there’s no better way to watch comedy films than among a cinema audience, with live musical accompaniment. This year will see dozens if not hundreds of Chaplin screenings in cities worldwide, many of them backed by large and small orchestras conducted by some of today’s top names in silent film music. This Saturday the San Francisco Silent Film Festival will bring Timothy Brock for his debut appearance at the Castro Theatre, where he will lead the SF Chamber Orchestra in playing Chaplin’s own scores for his first two feature-length films The Kid and The Gold Rush. Additionally, pianist Jon Mirsalis will accompany three of the best two-reelers from Chaplin’s fruitful Mutual period, The Vagabond, The Cure and Easy Street. Mirsalis is one of the regular accompanists at the Niles Essanay Silent Film Musuem’s Saturday night screening series, and as part of that venue’s year-long, chronological presentation of Chaplin’s Keystone shorts will play to Chaplin’s first movie-studio-set comedy A Film Johnnie, on February 22, nearly 100 years to the day after its original premiere.

Prints of Kid Auto Races At Venice, Cal. screen at both venues precisely 100 years after it was filmed at the canal-permeated seaside town (which was later incorporated into Los Angeles): January 11, 1914. Only Chaplin’s second completed film, it contains even less plot than the usual Keystone comedy, but already the soon-to-be star’s magnetism is evident. In the fact the film is all about Chaplin’s need to be on camera—and the camera’s need for Chaplin to be in front of it. Keystone honcho Mack Sennett frequently filmed comedy situations at public events, straddling the nebulous border between fiction and non-fiction. For instance, he’d entered a decorated car in the prior year’s Tournament of Roses Parade partly as publicity for his studio and partly as an opportunity to make a split-reel Sherlock Holmes parody with Mabel Normand and Fred Mace, called The Sleuths at the Floral Parade.

For Kid Auto Races At Venice, Cal., Chaplin, director Henry Lehrman, and a cameraman (or two, according to some sources) crashed a soapbox derby event crowded with spectators. This was the first audience for Chaplin in what would soon be known as his Little Tramp costume, which he’d put together just days prior to film the first shots of Mabel’s Strange Predicament, and we see the crowd reacting to his wanderings on the track, near-misses with racers, and battles with Lehrman and others to get closer to the camera so he can mug more effectively. Most of them appear delighted by his antics, although some shield their own faces from the machine’s stare. They realize just as much as Chaplin’s “odd character,” as he is called in a title card, that the camera can document them for a certain amount of posterity (surely nobody guessed a hundred years), and have an opposite reaction.

Chaplin’s “odd character” wore a fake mustache and was clad in oversized pants and shoes and a distinctive round bowler hat. He made a near-instant sensation among moviegoers once Kid Auto Races and Mabel’s Strange Predicament were released in early February 1914. By then he’d already filmed two more one-reelers in the costume, and had begun Tango Tangles, in which he played another drunk, this one bare-lipped. Throughout his year at Keystone, Chaplin experimented with his screen persona and attire, wearing a gentleman’s top hat in Cruel, Cruel Love, Mabel at the Wheel and The Rounders, or a city slicker’s straw hat in his sole feature-length film directed by another person (Sennett), Tillie’s Punctured Romance. He played a support role as a referee in his friend Roscoe Arbuckle‘s The Knockout. He even impersonated a woman in his Kid Auto Races follow-up A Busy Day, and in part of The Masquerader, a wonderfully self-reflexive piece in which he played a Keystone actor as his own inept doppelganger. But he always put his bowler back on for his next picture, performing as a waiter or a janitor or another humble figure. The Tramp was coming into focus and becoming a star, although the character’s identity wouldn’t be so solidified until early 1915 when, having been lured with greater salary and autonomy to Essanay Studios, Chaplin made a film called The Tramp just down the road from what’s now the Niles Essanay Silent Film Musuem.

By 1914, rapid industrialization had torn many workers from their homes and families, to whatever factories, mines, logging camps, etc. might offer employment. But a recession had made even this fragile sort of economic security unrealistic for a good number of job-seekers. As production slowed down at work sites, increasing numbers of Americans became dependent on municipal lodging houses and charities for their day-to-day survival. Chaplin was not a manual laborer but an entertainer, yet he felt solidarity with the down-trodden and began imbuing his portrayals with a sensitivity to character that was absent from the most brutally anarchic Keystone films such as The Property Man. Kenneth Kusmer describes Chaplin’s evolving depiction of poverty in his book Down and Out, On the Road: “Like many men on the road, Charlie has frequently been arrested; in a half dozen films he plays the part of an escaped convict. Although often scripted as an “idler” living an aimless existence, the Chaplin character is just as likely to be an unemployed worker looking for a job. Like many homeless men at that time, he is willing to accept any type of work, but his choices are limited.”

Chaplin had experienced real poverty growing up in London, and had grown used to being separated from his own family. His father had been absent, his mother institutionalized when he was fourteen, and his brother Sydney joined him from England only after his film career had been established. Though he was well on his way to unparalleled fame and riches, he was in a real sense still a rootless “vagabond”, traveling from studios in Los Angeles to Chicago to San Francisco in search of the perfect place to make the pictures he wanted. He came closer when signing with the Mutual Film Corporation in 1916; here he’d make two-reelers of unprecedented budgets, building elaborate sets to help spark gag ideas and rolling through vast quantities of film stock while developing his ideas on camera. The result was twelve exquisite two-reelers (One A.M., The Pawnshop, Easy Street and The Immigrant, etc.) that many consider the pinnacle of his career.

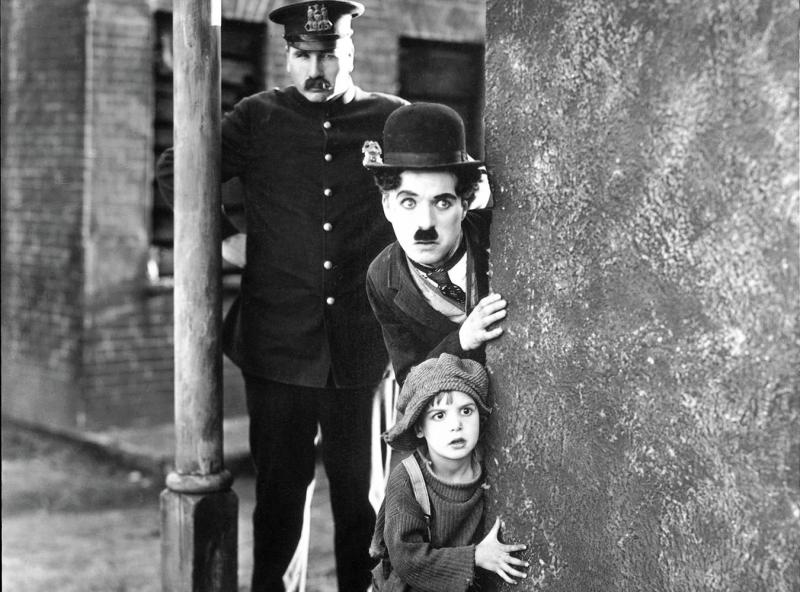

An eight-picture, million-dollar deal with First National brought him even more independence. He completed a new studio complex in Hollywood in January 1918, and slowed the pace of his release schedule while increasing each film’s storytelling ambition. No longer was Chaplin satisfied by ending his films after two reels with a frantic chase. A Dog’s Life and his World War I satire Shoulder Arms ran three reels apiece, and it was not long before he was ready to spend almost a full year working on what would be his first feature-length film as director. The Kid was painstakingly made; it took the equivalent of over three hundred ten-minute reels of film to produce the material for a six-reel film. But it was worth it; the film was the nation’s biggest financial success since The Birth of a Nation six years prior, showcased Chaplin’s and his leading lady (from the Essanay days) Edna Purviance’s gifts for comedic and dramatic acting, and made a child star out of Jackie Coogan, who played the title role and would ultimately grow up to play Uncle Fester on television’s The Addams Family.

The Kid was also a success with critics, and as a feature was taken up by many of the more serious ones who had refrained from weighing in on his shorter works. Francis Hackett of The New Republic recognized the contrivances in a plot about an unwed mother at wit’s end abandoning, and then regretting the abandonment of, her child who has meanwhile given a sense of purpose to the tramp caring for him. He saw them as a virtue on the writer/director/star’s part. “Chaplin knows that the story of his adopted waif is a joke between the experienced movie patron and himself. The merchantable maternal instinct and the surefire lost child and the beautiful Lady Bountiful and the glad reunion—he glides over them with a touch like a light beam. What he has to play with is his own gorgeous predicament”, he wrote. “From an industry The Kid raises production to an art.”

Such notices may have helped push Chaplin away from slapstick comedy, and from his own performer status, when writing and directing his next feature A Woman of Paris, in which he appeared, nearly unrecognizable, only in a tiny cameo. Audiences responded poorly to this comedy of manners, although it would prove a formative influence on the future works of Lubitsch and Ozu, and thus any (and there have been many) filmmakers following in their creative tracks. Still, for the first time a Chaplin picture lost money, and it was for the company he’d co-founded with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith in 1919, United Artists. It had taken longer than expected to complete his First National contract, and now his first truly independent production had flopped.

Chaplin wasted little time in putting his next film into production in December 1923. The Gold Rush returned the Little Tramp to the screen in a big way. It was his first “period” picture since 1915’s Burlesque on Carmen, but a hundred times more ambitious. The film opens with a spectacular recreation of an 1898 photograph of miners ascending the snowy Chilkoot Pass, the only route from Alaska to Dawson City and the other boom towns of the Klondike Gold Rush. In the most elaborate location shoot of his career, Chaplin brought his camera crew from Los Angeles nearly five hundred miles North to Truckee, California in the Sierra Nevada mountains to film the scene. He brought in six hundred unemployed Sacramento men by train to play the antlike line of prospectors streaming up to the pass. It was shot in a day.

The rest of the film was shot in Hollywood, where state-of-the-art sets and special effects convincingly evoked the Yukon winter complete with mountain trails, avalanches, and a gravity-challenged cliffside cabin. Perhaps the most memorable scenes are set at intimate tables however: when the Little Tramp and big Mack Swain sit down to make a meal of a leather shoe (in fact made of licorice uppers and candy nails), and when Chaplin manipulates a pair of dinner rolls into a dance for a company of delighted women observers. The Gold Rush is quite possibly the Tramp’s funniest film and greatest masterpiece, and made back its million-dollar budget more than four times over.

The Circus, Chaplin’s next film, is hardly less funny than The Gold Rush, as it contains hilarious scenes like a midway chase and a monkey-beset high wire walk. But it’s also a much more melancholy film than its predecessor, speaking very pointedly but unsentimentally to the gap between artist intention and appreciation. Perhaps this theme is one Chaplin could not have tackled had he not had under his belt the disappointment of A Woman of Paris, a film which he remained proud of for the rest of his life even few others agreed. Here the Little Tramp inadvertently makes a clown of himself and becomes star of the circus, but is tripped up by his own self-consciousness when trying to replicate this success. One wonders if Chaplin somehow felt trapped by his Tramp, as if he’d created something he’d never be able to completely control back in the Kid Auto Races of 1914.

By the time The Circus was released in early 1928, The Jazz Singer had already hit theaters and audiences were wondering when they’d learn how their favorite stars’ voices sounded. The biggest stars were able to keep them waiting the longest. Douglas Fairbanks was first heard in bookending segments of the otherwise-silent The Iron Mask in 1929. Greta Garbo‘s first talkie was 1930’s Anna Christie. Chaplin, still perhaps the biggest international star around, knew he had to contend with the sound revolution, but would the Tramp, a character born out of the pantomime stage tradition he’d perfected while touring with Fred Karno’s troupe for six years prior to his Keystone year, translate to the eardrum? What would he say?

Chaplin decided to use his new film City Lights as an opportunity to instead showcase his talent as a musician and composer, which he’d been honing privately for many years now. The Little Tramp would remain silent as he tried to live up to a blind girl’s mistaken impression that he was not a pauper but a millionaire with the ability to pay for a miracle cure. It’s probably Chaplin’s most elegant and heart-rending film, and in 1952 Sight & Sound magazine’s survey of international critics voted it, in a mathematical tie with The Gold Rush, the second-greatest film of all time behind Bicycle Thieves. From here on out Chaplin would write scores for all of his future films, and starting in 1941 begin to compose new ones for reissues of his First National and United Artists classics.

City Lights was another terrific financial success, but writing, filming, editing, and scoring it had taken more than three and a half years of his life, with significant breaks only to attend to his mother (whom he’d brought to California a few years prior) on her deathbed, and to recover from a severe case of ptomaine poisoning. In fact, he was about to turn 42 and the most extended vacation he’d taken since beginning his filmmaking career at 25 was a month-long trip in Europe in 1921. Esteemed visitors from around the world prized a visit with Chaplin if they stopped in Hollywood, from royalty to filmmaking royalty (Sergei Eisenstein, Ivor Montagu, Eduardo Ugarte and Luis Buñuel all visited his home on one 1930 day). But Chaplin had barely been anywhere other than California, New York, and the rail route between, in nearly a decade. So the day after his new film’s Los Angeles gala premiere, to which Albert and Elsa Einstein had been his personal guests, the star left on a trip that began as a publicity tour to the City Lights premieres in New York and London, and would extend to become a seventeen-month tour touching on four continents and connecting with more world leaders in politics and the arts.

It was a long trip, but overall more intense than relaxing. Everywhere he went he attracted thronging crowds. In Berlin he and his fans were railed against by Nazi newspapers insisting he was Jewish (a misapprehension he was proud to wear whenever it was hung on him, even and perhaps especially by anti-semites). In Tokyo he barely escaped an assassination plot by ultranationalists hoping to draw Japan and the United States into war with each other. He apparently was saved by a lucky, last-minute scheduling mishap; instead of being in the line of fire along with Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai who was indeed killed in the attack, Chaplin was out attending a sumo match with Inukai’s son.

Chaplin came back from this voyage with two perspectives that would have an impact on the next film he would make, Modern Times. He had more of a sense of what his films meant to people around the world. And he had much more of a sense of the real problems the world was facing in 1932, one of the worst years of the Great Depression. Modern Times would be his most overtly political film yet, and it was all the more important for it to connect with mass audiences for this very reason. The gamble of making and releasing City Lights as a silent film with recorded music and a few sound effects had paid off in every way, but for a major Hollywood director to continue to filming in the silent mode into the mid-1930s was balderdash. Audiences would surely knock down theatre doors for a chance to finally hear Chaplin’s own voice in a film. On the other hand, if the Little Tramp could already speak, without speaking, to people in every country in the world, why risk silencing him by giving him something to say?

In Modern Times Chaplin’s Tramp starts as a worker in a state-of-the-art factory. But the kind of progress practiced in this place is enough to send anyone to the madhouse. The Tramp wants to do what’s right but still ends up in and out of jail and in and out of jobs, all while putting the audience in stitches and out of breath. The friction generated when placing a fully-foibled human in a world of mechanized systems is the stuff that laughter is made of. Graham Greene, for one, felt that a comic bit with an automated lunch machine was the best scene Chaplin ever invented.

Modern Times uses more sound effects than City Lights, and even employs speech at various moments throughout. The words feel like intrusions into Chaplin’s mute universe, even though (especially since?) they’re never spoken to the Tramp directly but always through retro-futuristic intermediary machines. Finally, near the end of the film, Chaplin opens his Tramp’s mouth to sing a song. The melody is familiar, the words are gibberish, and the performance is one for the ages, a cry out against the technological prisons we’ve been shown through the rest of the film. Chaplin and the Little Tramp have succeed in the impossible: giving in to the march of progress only on their own terms.

It was inevitable that The Tramp would be retired after this moment, even if Chaplin himself was not ready to. Already in 1936, The Tramp was an icon of another age, and there were important things to be said, that would very soon need to be said in Chaplin’s own voice. In 1940 he made his first full-fledged talking picture, about not a homeless wanderer or a borderline indignant but a settled man, a defender of the ghetto—and about the tyrant he must defend himself and his community against. There are vestiges of The Little Tramp, even including his bowler, in The Great Dictator‘s Jewish barber character, but these are only traces, like the traces of pantomime and the art of silent film that appear in diminishing strength through all of the last five films Chaplin directed.

We may wish other film personalities of great talent could have been as recognized and rewarded, and as documented and deconstructed, as Chaplin was and has been. But that’s no reason not to join in a moment of appreciation for the singular presence that a certain “Little” but just as much “Great” writer, director, actor, and all-around man of cinema has been in the past hundred years of movie watching.