In Waking Life, Caveh Zahedi, quoting André Bazin, describes the “ontology of cinema” as the capturing of reality, the reality of God. Sounds simple on the face of it; just point the camera and turn it on, right? In our early films at UCLA, it was kind of like that. For Dog Story, we learned that a friend of ours, Keiko, an acting student, had an old dog that was starting to die, which was emotionally challenging for both her and her mother. The film was an effort to capture the physical and emotional reality of that event even as it was unfolding. A Little Stiff was a similar project, but it brought in a greater degree of re-enactment; a version of the events in the movie happened in real life, and they happened to the very people that appear in the movie, but they were revisited months after the original events. That movie has the special quality it has, I think, because the reality of actual history shines through, the feel of actual people and their inner lives shines through. In contrast to most Hollywood movies, we weren’t trying to create something out of whole cloth, we weren’t working up an appearance of reality from smaller, artificial parts; rather, we were re-stitching whole people, their places, and their events so that the camera could record them.

But capturing reality is, ultimately, more complicated than that, and I think the rest of Caveh’s body of work is a testament to that complication. A Little Stiff, compared to Dog Story, was already a step in that direction. What makes A Little Stiff different from Dog Story is that the subject of the plot is Caveh himself; it recounts something that happened to him, and the movie captures, in part, Caveh’s psychic adventure. In other words, compared to Dog Story, A Little Stiff was a project of self-examination, and therefore self-exposure, on the part of the filmmaker.

I Don’t Hate Las Vegas Anymore strides more boldly in that direction. Here is the alchemical mix for that movie: his real family members + real family history (their trips to Vegas) + real (not hidden) filmmaking + let’s see what happens. Of course, Caveh supercharges the entire mix with his plan to get his brother and father to take Ecstasy with him, but that is precisely the filmmaker’s effort to try to pay attention in a certain way: “I, the filmmaker, claim there is a reality of love beneath the alienating habits of family. Let’s go there again, do those things again, and see if we can find it.”

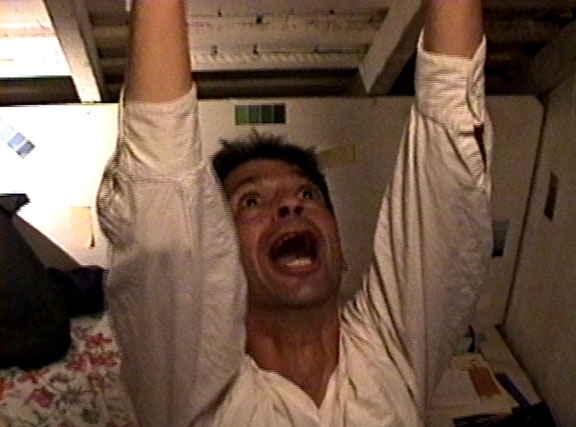

As anyone who has seen his movies knows, this near-Augustinian impulse to confession and self-exposure is the other great force in Caveh’s filmmaking, and it is the other side of the coin in any thorough-going vision of reality (which is one way of appreciating the most important, animating insight of Augustine himself: that to understand ultimate reality you have to move through the deepest parts of the self). So, to add to Bazin, if reality is God then reality must account for the self, too—whether it is to be found in day-to-day life (Bathtub) or in ecstatic experiences (I Was Possessed by God and Vegas, for example).

So in the end, of course, it’s not as simple as turning on the camera. The viewer and the cinematographer have to be factored in, too. Cinema (and perhaps all art) is about attention, about an act of consciousness. What’s interesting to me about Caveh’s work as a whole is precisely the degree to which he brings himself into the process—his films record the act of consciousness of the filmmaker, of someone paying attention. This “paying attention” in a particular way is, I suppose, what all filmmakers are doing. Even Hollywood has its way of paying attention (though exactly what kind of attention is it, and what are they paying attention to?). So, perhaps better put, Caveh’s movies are the record of Caveh trying to pay attention, in the act of trying to pay attention to what’s really going on. That, I think, is what makes his movies so exciting. Seeking to pay attention to what’s actually going on will always involve drama, will always be exciting, because it challenges our habits of mind, habits of mind that can serve as a kind of blindness. So, to try to pay attention means you’re not going to be entirely in control. Mainstream movies, of course, are all about control: control the content, control the product, control the audience. But if you’re trying to pay attention to what’s actually there, then you’ve gone out to meet something, and, therefore, you can’t be fully in control because you don’t know what you’re going to find (the reality outside), and you don’t know who you are going to be when you find it (the reality inside.) All of Caveh’s movies work in this way: there’s something to be seen, but it’s something that can be seen only if you’re willing to pay attention to the way the filmmaker is paying attention, if you’re willing to take risks the way the filmmaker is taking risks. Making the act of paying attention part of the object of the film itself comes off to some as self-absorption. Perhaps you won’t like it—it’s a matter of taste, in the end—but we encounter the world through the self, and Caveh is courageous enough to let that act of encounter guide his art. You may not like it, but it’s serious art nonetheless.

When it comes to the process of filmmaking, there’s a particular version of this dynamic with I Am a Sex Addict that was made possible by the digital revolution. Making movies with film stock was high stakes because putting reality to film was so expensive. With video, there was both more to record and, more importantly, there was a more creative feedback process in the editing. The process became more writerly in the sense that you could try things, revise, and create on the basis of what you were getting, not on what you had already conceived. In the script model of making movies, what is filmed conforms to what has already been conceived. In Caveh’s process, especially with the addition of digital technology, your creativity can be in conversation with what the camera is finding along the way. The Sheik and I is an even more explicit step in that direction. Caveh sets out, camera in hand, to find the film he’s making, and therefore makes a film about the forever embattled grounds of what we should and should not pay attention to. And, for me, that is ultimately a humanizing endeavor. To be human is to be awake to the fact that who we are and where we are going requires that we pay attention, communally, and as honestly as possible, to the ever-changing, constantly created act of culture. Caveh’s movies reveal and celebrate that often uncomfortable (but also sad and hilarious) space.

So, to come back to Bazin’s ontology, I’m reminded of what is called the observer effect in physics, the idea that the very act of observation has an impact on what is being observed. To move the ontology of cinema in that direction, then, has to be more complicated than a recording device and the reality it’s recording. The real observer in cinema is not the device but the filmmaker, and the observation is the filmmaker’s act of consciousness, of paying attention, an act of consciousness mediated by the camera. Is that the reality of God? That depends on what you mean by God, but it’s certainly closer to reality than the vast majority of movies.

The complete Caveh Zahedi box set, Digging My Own Grave, is available from Factory 25: factorytwentyfive.com/caveh/.