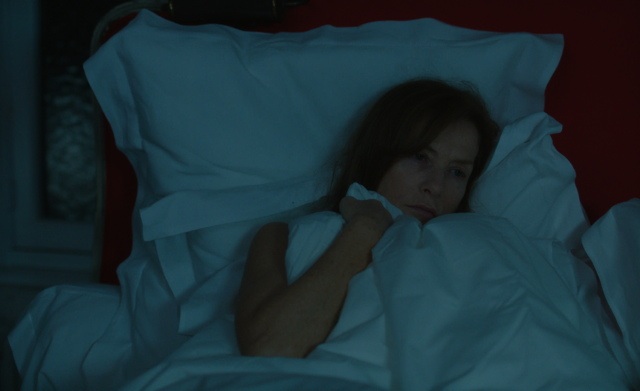

Catherine Breillat has always created cinema that was close to the body. Some viewers are thrilled by this level of sincerity. For others this lack of solid distance feels suffocating, intimidating and uncomfortable. With Abuse of Weakness (now playing New York Film Festival), Breillat has crossed yet another boundary; this time the script’s relationship to her own private life is not only easily discernible, it’s undeniable. The story of middle-aged film director Maude Shainburg (Isabelle Huppert) and charismatic conman Vilko Piran immediately brings up real life, in that a couple of years ago Breillat herself started collaborating on a film with a man, Christophe Rocancourt, who swindled her. Eventually he was sentenced to prison with the unique criminal charge of “abuse of weakness” that inspired the film’s title. In the film Shainburg suffers a brain hemorrhage and retains a partial control of her body, never fully recovering. Breillat suffered a stroke that left her severely debilitated. Such a story could have easily been turned into a sentimental tear-jerker, but Breillat would never allow it: she stays close to the body, keeping the atmosphere strange and comical. How does it feel to be unable to tie your own shoes and how can it make you want to accomplish the impossible? What is intimacy? Why does sexuality make viewers uncomfortable? During our meeting at the Toronto International Film Festival, Breillat was brilliantly honest, disarmingly funny and deeply inspiring.

Keyframe: Your films always start from a very personal emotion, experience, memory. Abuse of Weakness is no different in this aspect. But the story behind this film is very unusual, for many reasons. Is this film special to you?

Catherine Breillat: I think it is very particular film. In France the one that’s abused never ever files the complaint. Usually it’s the family that does it [for them]. No other woman, or man, an intellectual adult, has lived through a story like this. It is almost impossible to prove that you were a victim of abuse of weakness. When you are a victim you don’t think this way. But I did it, I filed a complaint myself. It was the first time in France [the victim’s complaint was acknowledged]. Even the judge told me that it has never happened before. At the same time I shot three films, published two books…not completely at the same time…but close. Soon after I also started having an epileptic crisis on a very severe, dangerous scale. I was close to dead.

Keyframe: Exactly like Shainburg, played by Isabelle Huppert.

Breillat: I very often inspire myself by a new item—fat girl, perfect love—and mix it in the character I invent for the story. But the story is very often also inspired by things I see around me. Here, these inspirations are not new. [After I had the epileptic crisis] they gave me pills, very very strong, almost the same as the ‘rape drug.’ [When you’re on them] you become a freak, you don’t know what you’re doing anymore….When I had an epileptic crisis, I spent four days in the hospital and I remember nothing. It’s impossible to remember, so the character has no idea she wrote this fat check for him. Remember when Vilko comes to the hospital to pick her up? It should be her son to do that. But she’s in intensive care, there is an encephalogram attached and several tubes. At the end what she says is that what they gave her was like a rape drug.

Keyframe: How do you remember your relationship with Christophe Rocancourt, who inspired the character of Vilko? Watching the film the dynamics between Shainburg and Vilko are sometimes hard to comprehend.

Breillat: When the newspaper first wrote about this story [that happened to me] people were laughing:’Oh, he gives his arm to her to walk outside, he cuts her meat’… I was always in my flat, alone. I want to love. It makes me laugh. It was a strange relationship [with Rocancourt], we were like two adolescents. When we were spending nights together it was like at school, when you’re in a dorm with your best friends. [The scene when they spend a night together in a country house] was like a scene from an American movie with Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant, this sort of a film, so strange and charming….He was a best friend. We were like two girls, speaking about love and heartbreak. I think it is a really great subject.

Keyframe: The physicality is very important in Abuse of Weakness but it’s different than in your other films. Usually the sexual context is much more present. Why do you think people react to it so strongly?

Breillat: It’s normal [they do]. Many people cannot handle knowing what they truly are. It’s too difficult. And sometimes, with all the people around them in the cinema they often feel shamed. They stop being spectators and start being people who feel shame. My way of work is not to show a spectacle but to hide myself inside the movie like that [covers herself with a scarf]. It’s too much, for them it’s too much. They confuse themselves and the person. It’s normal in the movies that we translate ourselves into the character, but with a distance. No me. When I’m shooting a sex scene, I’m always trying to tell my actors that as a viewer I want to feel as if I were between their two bodies, [not in front of the screen]. This is why the spectator is feeling uneasy [watching my films]. They are not looking at it, they are being sucked, immersed into it.

Keyframe: You have a very unusual way of working with the actors and establishing your position on set. Can we talk about that?

Breillat: I always shoot my films like that [covers her eyes with her hand]. I don’t want people to see my emotions, my face. If they see me like that on the set, I immediately change my facial expression, so nobody can know what I think or what I feel. Once the scene starts I don’t ever speak to my actors. I think it’s good, because usually the scheme is you say ‘Action!’ and they immediately feel in control, think ‘Oh, I’m an actor!.’ How I work makes them feel more uncomfortable, uneasy, they have to wait, then they begin to act. I never say ‘cut’ either.

Keyframe: How did you decide on casting Kool Shen as Vilko Piran? He’s a non-actor, and you very often work with such, but it is still a very unusual casting choice.

Breillat: My male character could have not been an actor. I wanted a body, I wanted someone who really engulfs the space with their physicality. Very sexy, a little brutal. It’s not beauty and the beast story, but…There is an intellectual abyss between them [Shainburg and Vilko]. So I thought: I need a rapper! I don’t know any rappers and know nothing about rap. So I Googled him. I knew his group, it’s a cult group in France. They were the first to have such violent lyrics about killing the police etc. Their name is Suprême NTM which means ‘fuck your mother.’ I figured Kool Shen, the most violent of the bunch, would be the best [to play Vilko].

Keyframe: So, on one hand we have a violent rapper, on other—France’s biggest living film star, Isabelle Huppert. The most unusual, outstanding duo….

Breillat: One actress, one professional was enough. It’s very easy to find a young actress, someone who has never been in a film, like Fu’ad Aït Aattou in The Last Mistress. She has never been in a movie before, I saw her in a cafe and asked whether she’d like to be in my film. I do that very often. Isabelle is older. I think it is impossible to find a mature woman who is not a professional actress, but is capable of acting. So I knew I wanted her. We are friends, but when it comes to professional decisions, it doesn’t matter. She’s very tough, just like me. And at the same time when she’s not acting, not working, in everyday life she’s a little girl. And me, I am an adolescent. So we have something that we share, like twins. She’s younger than me, a very cerebral actress, but a child at heart. Such combination doesn’t really exist in France.

Keyframe: Her character’s life is marked by duality: Maud Shainburg is a powerful, brilliant woman locked in a cage of a disabled body, fighting with her debilitated physicality. You experience that as well.

Breillat: When I shoot it’s easy for me to live with the body I have. I always have a personal assistant who helps me to wear my [orthopedic] boots – and they are very complicated to put on and tie even with two hands, not to mention one! When I am alone in my flat, just to stand up in the morning is horrible. I cannot go outside on my own. [There were times when] I was a prisoner in my flat.

Keyframe: The obstacles seem to only encourage you to cross boundaries. You are a fighter, and so is your character.

Breillat: My character is like that, always doing things she cannot do, like me. [for example] in Bluebeard there were turning stairs. Normally I’d never be able to climb them but somehow when I’m working such things are becoming possible. When I am making cinema I become another person, I do things I normally cannot do. This is who I am. It’s hard to understand, was for the court. [Laughs.] But it is like: you know this man who has no arms and no legs but crossed the La Manche Channel from France to England? If he had his limbs he’d never even want to do that. But he doesn’t. So he has to. I have to do things that are very dangerous, things that are too much for me.

Keyframe: This project might have been just this. You tried to film the similar project your character is trying to execute in the film. And didn’t succeed.

Breillat: I knew that if I shot this film with Naomi [Campbell] and [Christophe] Rocancourt I’d succeed, I just knEw that. But it was supposed to be in English and in France getting money for such project is very difficult, they are very protective and want to subsidize French-language films only.

Keyframe: People immediately see you in the character of Maude. Does it bother you?

Breillat: I don’t care if people recognize me in my character or not. I always work alone. I have no censorship. Even though this film somehow repeats the pattern of my life, to me these were scenes. It’s [not only based on actual events but] also fiction—I can’t speak of my story if I say ‘I.’ I’d immediately start crying. But when the female character is [called] Maude, it’s my passion of cinema, it’s not the same. On the set I’d always say ‘She does, she says’, not: ‘I do I say.’ It’s makes it impossible to envision as me. Even if it is exactly the same.

Keyframe: Exposing yourself through art seems like the most intimate of gestures. Is this what artists have to do?

Breillat: Shooting a film all the artists expose themselves totally. If you want to hide behind your work you expose yourself even more. Because not only you show the world who you are but also what you don’t want people to know about you. In my life I have never invented [something from a scratch] for a movie or a book. I mix new items with me, or somebody I know or heard. I never invent. It’s just like that. I don’t film make films based on what happened in reality. I always have this detachment.